By JOHN MINAHAN (Avon; 1977)

By JOHN MINAHAN (Avon; 1977)

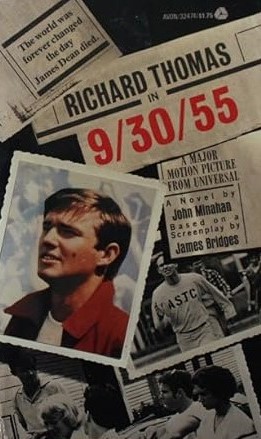

A movie novelization, emerging from the format’s golden age, that until recently was as obscure as the long-forgotten film it novelizes. 9/30/55 has movie novelization buff Quentin Tarantino to thank for its current popularity on the cult circuit, as he’s claimed in multiple interviews that it’s his favorite book.

It’s certainly unique, with John Minahan, one of the top novelizers of the 1970s and 80s (other Minahan novelizations include SORCERER, MASK and EYEWITNESS), offering a significant expansion of the film’s narrative. Another facet of the book’s uniqueness is its publication history, with the film having been completed in 1977 but withheld from release for two years and undergoing a title change (to SEPTEMBER 30, 1955), meaning 9/30/55 ended up having a standalone release in ‘77 and a title unique to itself—which, as we’ll see, was an entirely appropriate state of affairs.

SEPTEMBER 30, 1955, which partook of the coming-of-age 1970s movie craze (SUMMER OF ‘42, BREAKING AWAY, etc.), was an autobiographical effort from writer-director James Bridges, recounting his life as a teenager affected by the untimely death of James Dean on 9/30/55. College football star and Dean fanatic Jimmy (played by Richard Thomas), residing in a depressed Arkansas community, learns of the tragic news on 10/1/55. Together with a group that includes the proto-goth gal Billie Jean (Lisa Blount), Jimmy embarks on a rambling succession of grief-spawned misadventures that include robbery, reckless driving and a séance, and climax with a near-fatal injury.

Minahan relates his text in the first person and (as Dean Koontz did in his FUNHOUSE novelization) adds a lengthy prologue of his own invention. That prologue, comprising the book’s entire first half, takes place largely in 1953, and exists to flesh out Jimmy’s background. Among Minahan’s inventions are a deceased sibling and another movie star obsession: Marlon Brando, with whom Jimmy becomes besotted after viewing A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE, thus transforming the narrative from a depiction of one portion of 1950s pop culture to a veritable summation of the decade’s first half, in which Brando and Dean laid the foundations for the popularization of rock ‘n’ roll (for good measure, Elvis Presley gets a mention).

Also expanded considerably is the character of Billie Jean, who emerges as a far richer, and sadder, individual than the mysterious seductress of the film. Here’s she’s given to thoughtful monologues outlining her checkered dating history and ambitions to become an actress (admitting at one point that “I don’t know why I’m telling you all this, it just—all came out”).

The book’s second half recounts the events of the script, which take place over the course of a few hours, and so clash with the panoramic first half. The ending, in which Jimmy has a final heart-to-heart encounter with a wounded Billie Jean, was altered considerably from the film’s denouement, with BJ offering another of her impassioned monologues and the narrative cutting off rather than properly concluding.

So the book isn’t perfect (something movie novelizations rarely, if ever, are). It does, however, offer a deeply felt and compellingly individual take on a format that tends to be extremely limited in ambition and execution—in short, 9/30/55 comes very close to succeeding as a Real Novel.