The 1980s, to be sure, contained more than its share of zombie media. The decade’s zombie-themed standouts included Lucio Fulci’s 1981 film THE BEYOND and Stuart Gordon’s 1985 RE-ANIMATOR, Joe Lansdale’s 1986 novella DEAD IN THE WEST, Candace Caponegro’s 1988 novel THE BREEZE HORROR and J.R. Bookwalter’s ‘88 feature THE DEAD NEXT DOOR, which contained a depiction of a zombie apocalypse that was unprecedented in its scope. As it turned out, Bookwalter’s film, and the preceding entries, were merely appetizers, with the main course arriving, arguably, in the following decade.

We all know the particulars of zombie lore. As established by George A. Romero’s NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD in 1968 (yes, there were zombie themed films and books before then, but it was Romero that provided the template for modern-day zombie lore), the living dead abide by several hard-and-fast rules: they shuffle and stagger, have an overpowering craving for (live) human flesh, can be put down only by a bullet to the head and transmit the zombie contagion by biting non-zombified humans.

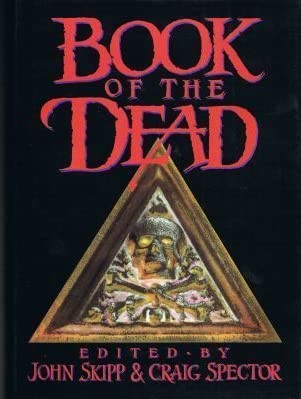

With those things in mind, let’s look back to 1989, which saw the publication of three noteworthy books that dealt with the living dead: the novels THE DEAD by Mark E. Rogers and SHE WAKES by Jack Ketchum, and the John Skipp-Craig Spector edited splatterpunk anthology BOOK OF THE DEAD. The latter was especially noteworthy in the zombie arsenal, as its stories, by authors like Stephen King, Ramsey Campbell, Richard Laymon, Joe Lansdale and Robert McCammon, were set specifically in the universe of George Romero’s films on the subject (with Romero himself providing a forward). Fictional tributes to Romero would become commonplace in the 00s, in the fiction of Kim Paffenroth and others, but in 1989 the concept was somewhat radical; hard though it might seem to believe now, back then the idea of a zombie apocalypse still seemed subversive.

BOOK OF THE DEAD also deserves credit for containing two classic stories: “Less than Zombie” by Douglas E. Winter, which adroitly spoofed the 1980s chic of Brett Easton Ellis’s LESS THAN ZERO, and “Wet Work” by Philip Nutman, a short and stark account that detailed the outrageous carnage wreaked on the living dead by zombie-killing hitmen (Nutman later expanded the story to novel-length—see below).

It may seem inappropriate to discuss a 1989 publication in an article about the nineties, but many of us didn’t actually get around to reading BOOK OF THE DEAD until then. There’s also the fact that BOOK OF THE DEAD spawned a follow-up anthology, STILL DEAD: BOOK OF THE DEAD 2, in 1992. It followed the perimeters of most sequels in that its returns were considerably diminished from those of its predecessor, but it did contain some strong entries. Foremost among the latter were Douglas E. Winter’s “Less than Zombie” follow-up “Bright Lights, Big Zombie,” which did for Jay McInerney what the former story did for Brett Easton Ellis, and Elizabeth Massie’s “Abed,” an authentically disturbing depiction of zombie-fied perversion (which was adapted for film in 2012).

By the advent of the nineties it seemed the zombie floodgates were wide open in fiction, and certainly film. Many believe that in the 1990s (as THE LIVING DEAD co-author Daniel Kraus wrote) “zombies were persona non grata,” yet I’d opine that zombie cinema reached its apotheosis then, with entries that encompassed the comedic, the arty, the futuristic and the surreal. As for the zombie literature, it wasn’t quite as varied, but did contain some reasonably strong entries.

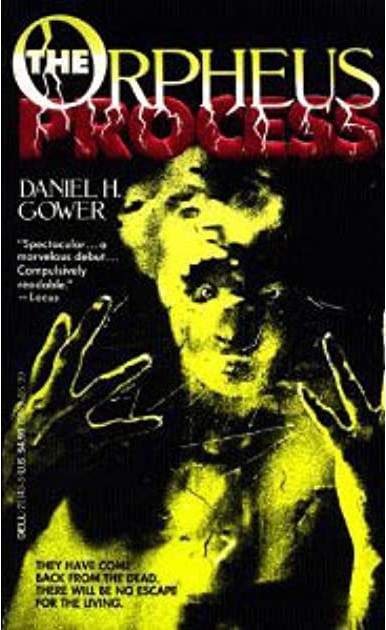

THE ORPHEUS PROCESS by the debuting Daniel H. Gower appeared in 1992. It concerns Dr. Orville Helmond, a scientist obsessed with raising the dead. To this end he performs unethical experiments on various lab animals, and also his just-killed daughter Eunice. All seems well initially, but then Helmond discovers that his experiments—Eunice included—display unexpected side effects, leading to an increasingly outrageous stew of mass zombification, bloodletting, shapeshifting (the living dead on display here can change form and resurrect their dead fellows), insanity, mass destruction and, of course, death.

The novel is unique in its mixture of sophistication and exploitation. Included are learned dissertations on the ethics of Helmond’s experiments and philosophical ruminations about zombiedom (with Jesus Christ, Prometheus and Faust all brought up), appearing alongside a passages like this one: “Stomping a guinea pig underfoot, he pinned a rhesus between his bicep and armpit, shoved the gun barrel against its head, and watched it split like an egg when he fired.”

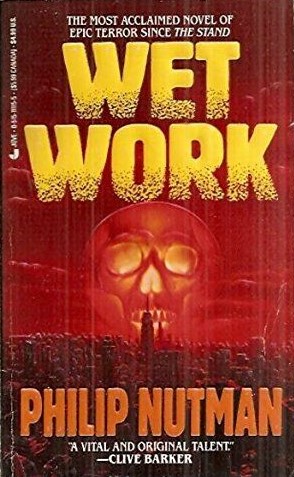

It was followed in 1994 by WET WORK by Philip Nutman. An expansion of the abovementioned BOOK OF THE DEAD story of the same name, it was Nutman’s first and only novel, and his inexperience was evident in the wobbly multi-viewpoint narrative. Here the US based zombie contagion of the story is fleshed out, with characters that include the president of the United States (based directly on George Bush, Sr.) and a CIA appointed hitman who’s just returned from Panama. A comet is passing by the Earth that causes the dead to rise, leading to an “infernal Disneyland for the Damned” that in the retinue of zombie apocalypses is pretty standard.

What’s interesting is the book’s presentation of the inner lives of its zombies. In keeping with the original short story (whose zombie killing protagonist was eventually revealed to be a deader himself), WET WORK’s living dead are a far cry from the mindless, shuffling ghouls of most zombie lore. These zombies think, reason and occasionally attempt to staunch their craving for human flesh. Thus WET WORK is a disappointment, but not a complete loss by any means—plus it contains what I believe was the first-ever allusion to REM’s immortal tune “It’s The End Of The World As We Know It (And I Feel Fine)” in a work of fiction, which is, needless to say, a most appropriate reference.

Moving on to zombie-themed cinema, the nineties commenced with a passable Tom Savini helmed remake of NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD. Savini’s directorial debut, this NIGHT is neither as terrible as its detractors have claimed nor as brilliant as its fans believe, being, again, merely passable. It’s certainly no substitute for the original.

Also appearing in 1990 was THE LAUGHING DEAD, the appalling directorial debut of novelist Somtow Sucharitkul (a.k.a. S.P. Somtow). Quite simply: the less said about this film the better. The following year’s BATTLE GIRL: THE LIVING DEAD IN TOKYO BAY (BATORU GARU: TOKYO CRISIS WARS), from Japan’s prolific Kazuo ‘Gaira’ Komizu (of the notorious trash fests GUTS OF A VIRGIN and ENTRAILS OF A VIRGIN), was only marginally better. About a young woman (Cutei Suzuki) who becomes a one-person army in a futuristic Tokyo overrun zombies and punk gangs, it has some good ideas but is done in by a too-low budget and an overly conservative approach. Gaira appears to have been trying for a more general audience-friendly film than his earlier efforts, and the finished product suffers for it.

It was succeeded, thankfully, by the New Zealand lensed BRAIN DEAD (released in the US, in edited form, as DEAD-ALIVE) in 1992. The third film by Peter Jackson, BRAIN DEAD was (and might still be) the goriest movie ever made, and also one of the funniest. It’s a comedic zombie mash in the mold of EVIL DEAD 2 (1987) that for me outdoes the former film in every respect. Jackson makes no concessions to subtlety or refinement, with innards jumping out of bodies and farting, zombie babies wielding severed arms and the hero vanquishing his undead tormentors with a lawn mower in a film whose invention and ingenuity continually amaze me.

The third film by Peter Jackson, BRAIN DEAD was (and might still be) the goriest movie ever made, and also one of the funniest.

Sam Raimi’s ARMY OF DARKNESS, also hailing from 1992, was the third entry in the EVIL DEAD franchise. It’s the most problematic film of the lot (existing in at least three different versions, none of which are entirely satisfying artistically), but Raimi’s overall conceit, of mixing EVIL DEAD styled horror with JASON AND THE ARGONAUTS styled action, is a good one. Yes, the eight-year-old aimed gags are hopelessly annoying, but there are some striking Harry Harryhausen-esque special effects, and Bruce Campbell is enormously fun to watch in the goofy-heroic lead role.

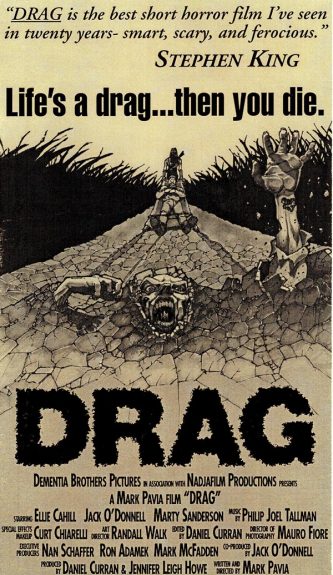

The 40 minute DRAG (1993) is among the most ambitious zombie films of the nineties, with a real sense of otherworldly desolation that defies its non-budget. Further pleasing elements include some audacious visual flourishes (a hurled rock POV, etc.) and a skillfully crafted narrative that begins in standard horror film fashion but gradually morphs into an eccentric-but-affecting love story, spliced with brief splashes of well-placed gore. The acting could be bit a stronger overall, although Ellie Cahill essays the lead role quite ably—which, as it turns out, is enough to fuel an ingenious piece of work that may not seem as fresh as it once did, but fully retains its underlying excellence.

1994’s SHATTER DEAD is a slick and stylish shot-on-video production about zombies co-existing with the living. That compellingly wacky premise gives the film an arrestingly surreal veneer, and writer/producer/director Scooter McRae (of the 1999 SOV feature SIXTEEN TONGUES and 2015 short SAINT FRANKENSTEIN) does not skimp on the gore. This film would be a classic if it weren’t so painfully slow moving and artsy.

1993’s CEMETERY MAN (a.k.a. DELLAMORTE DELLAMORE) was an uncommonly stylish Pastaland horror fest starring Rupert Everett as the world’s most laconic cemetery keeper. The dead are coming back to life around him, an occurrence he reacts to with the same droopy nonchalance he treats everything else in his life. Writer/director Michele Saovi really came into his own here after helming a series of Dario Argento clones; CEMETERY MAN, by contrast, is a totally original, fully assured creation from start to finish. I’ve always been a little cool on the film’s meandering final third (which I once dubbed “a nightmare in itself”), but do find myself warming to it after all these years.

The unfortunately monikered LAUGHING DEAD (unfortunate because it means the film will be confused with THE LAUGHING DEAD—see above) is an American made no-budgeter from 1998. The non-budget is evident in the notably underlit super 16mm visuals, but writer/director Patrick Gleason lends the proceedings a powerfully brooding aura. Dissolves and slow pans mark this dark tale of an insomniac (Gleason) making his way through a nightmarish future world where the dead walk and the living behave quite poorly. The film has been criticized for the fact that the laughing dead of the title have to play second (if not third or fourth) banana to vampires, giant pigs and deranged reality TV hosts, but Gleason’s outsized ambitions are impressive—and are (for once) largely fulfilled.

Hong Kong got into the act in 1998 with BIO-ZOMBIE (SUN FAA SAU SI). It contains an example of something that would become quite controversial in the zombie pantheon: the “fast zombie,” which in the context of an ultra-kinetic Hong Kong thrill fest makes total sense. The plot, unfortunately, is complete nonsense, with several goofballs trapped in a shopping center in the midst of a zombie outbreak caused by contaminated soda(!). The resulting nastiness is never less than totally compelling (even when the film’s sense of humor is at its most childish and moronic), and leads to a shockingly bleak ending. Further noteworthy elements include the onscreen stats that appear in one scene detailing the protagonists’ various abilities, and the “reload” icon flashed in another, both intended to evoke the rising popularity of video games.

Speaking of which: here I’ll have to mention the zombie-themed video games that appeared in the 1990s. ALONE IN THE DARK premiered in 1992 and the massively influential first-person shooter game DOOM debuted the following year, followed by RESIDENT EVIL, DIABLO, THE HOUSE OF THE DEAD and SILENT HILL. Nearly all of those games were adapted for film in the following decade, in which living dead fever overtook popular culture like (forgive the cliché) a swarm of zombies.

The nineties zombie explosion ended with a definite bang—albeit not the positive sort. The “Expanded and Enhanced” NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD 30th ANNIVERSARY EDITION, released by Anchor Bay in 1998, contained fifteen minutes of new footage shot by NOTLD’s co-writer John Russo. This new version was, in essence, an entirely new film, with a new beginning that introduces a poorly acted priest character who wasn’t in the original NIGHT, and an open-ended conclusion in which said priest returns, suggesting that Russo was intending to use George Romero’s immortal classic to start an entirely new franchise (which thankfully never came to pass).

I’ll refrain from detailing this pic’s annoyances (as doing so would take far more space than I’ve got), but will report that it’s a poorly paced, unscary and thoroughly misconceived travesty about which the best I can say is that it was an honest failure rather than the cynical cash-in so many commentators have dubbed it. This is to say that Russo appears to have truly believed he’d created something profound, as evinced by a recollection from Romero about how Russo proudly screened this new cut of NOTLD for Romero and his wife, “hoping that we would have nice things to say and neither of us did. I just thought it was ridiculous.” That’s putting it mildly.