On August 7, 2023, film director extraordinaire William Friedkin, a.k.a. Hurricane Billy, passed away. Friedkin made films typified by (in the words of author Thomas D. Clagett) “Aberration, Obsession and Reality,” and existed in a realm similar to that of his contemporary Francis Ford Coppola, whose legacy is upheld by just two films: THE GODFATHER and APOCALYPSE NOW. In the case of Friedkin those two films are THE FRENCH CONNECTION and THE EXORCIST, a pairing so iconic it doesn’t really matter what came before or after—and a good thing, because as we’ll see, Friedkin’s pre-FRENCH CONNECTION and post-EXORCIST filmography was extremely uneven.

Here’s my personal ranking of Friedkin’s films. I’ve left off his extensive television work, and also (with one exception) his documentaries, to concentrate on the features for which he’s best known. You can probably guess my number one selection, which is of course…

1. THE EXORCIST

An obvious choice, yes, but a correct one. Friedkin himself recognized that this 1973 freak-out would be his defining film, and he wasn’t wrong. I admittedly have some problems with it, but THE EXORCIST remains a shocking, gritty, groundbreaking film with impeccable production values and superbly edited demonic freak-outs. It may not be the greatest horror movie ever made (although I’ve heard some compelling arguments that it is), but THE EXORCIST nonetheless ranks with the absolute best the gene has to offer.

2. THE FRENCH CONNECTION

At a nineties-era revival screening of this 1971 classic I recall overhearing a fellow patron complaining that the film played “like a TV show.” Well yes, but only because so many TV shows have imitated THE FRENCH CONNECTION’s streetwise aesthetic, which saw Friedkin mining his documentary roots to set the standard for gritty action in cinema (with the film holding up much better than similarly minded grit-fests from years past like MADIGAN and THE DETECTIVE). Many scenes were “stolen” in actual NYC streets, freeways and subway tunnels, a practice that extended to the film’s most celebrated sequence, the nerve-jangling car-subway chase shot amid real traffic. The film also boasts Gene Hackman as Popeye Doyle, certainly the most memorable movie tough guy since the heyday of James Cagney.

3. SORCERER

A notorious 1977 bomb that, as with many underappreciated Friedkin films, has undergone a dramatic reappraisal. It’s a remake of H.G. Clouzot’s classic WAGES OF FEAR/ Le salaire de la peur (1953), about four desperate men driving two trucks filled with nitroglycerine through harsh terrain in order to put out an oil fire. The South America set SORCERER has its virtues, including lush yet forbidding visuals (Friedkin resists the temptation to make his jungle scenery look pretty) and an awesome sequence involving the trucks going over a rope bridge. But the first hour, which literally jumps all over the planet, is confusing, and the action sequences are distractingly choppy, as if Friedkin left crucial footage on the cutting room floor—an issue that affects even the aforementioned bridge sequence (which furthermore cheats: given all the unbelievable thrashing around to which the trucks are subjected, both would be blown sky-high). And who precisely is that guy who gets out of the car in the end? Yet I’ve found myself continually returning to SORCERER over the years, more so, in fact, than the above films, so clearly there’s something to it that transcends criticism.

4. TO LIVE AND DIE IN L.A.

My reaction to this 1985 film mirrors that of SORCERER (down to the final scene, which in contrast to that unknown man getting out of the car in SORCERER has some unidentified people getting into a car): I have a lot of issues but find it oddly addictive. If FRENCH CONNECTION played “like a TV show” then TO LIVE AND DIE IN L.A. does too, in this case MIAMI VICE, and comes complete with an outrageously eighties-centric Wang Chung soundtrack and much generic action movie dialogue (“I’m gonna get that asshole and I don’t give a shit how I do it!”). But the excellence of cinematographer Robbie Muller’s burnished imagery is undeniable, as is the ultra-intense lead performance of William L. Peterson (who essentially replayed the role in most of his subsequent 1980s film appearances) and the justly famous car chase down the wrong lane of the Long Beach freeway, which comes damn close to outdoing THE FRENCH CONNECTION’s chase sequence. Based on a novel by ex-secret serviceman Gerald Petievich, which I read eons ago and, as I remember, liked.

5. BUG

Reviewers tended to evoke THE EXORCIST in describing the schizophrenic nightmare that is BUG (2007), but I’d liken it to a lesser-known Friedkin work: “Nightcrawlers”, a 1985 episode of CBS’ NEW TWILIGHT ZONE, about a disturbed Vietnam veteran who sucks the residents of a roadside diner into an all-too-real ‘Nam flashback. BUG has a similar aesthetic, being the wildly claustrophobic account of a deranged Desert Storm vet (Michael Shannon) who in a manner similar to the protagonist of “Nightcrawlers” shares his delusions about ravenous bugs, mind control and other fun things with a needy young woman (Ashley Judd) who comes to experience them herself. In true Friedkin fashion the film is relentless in its unvaryingly grim trajectory, with an apocalyptic finale that contains nary a hint of redemption, much less optimism. The performances of Shannon and Judd are appropriately raw, fearless and not a little overwrought, much like the film itself. Polished and entertaining? Not exactly. Arresting and thought-provoking? Most definitely.

6. KILLER JOE

This 2011 indie saw Friedkin venturing squarely into Quentin Tarantino territory. KILLER JOE is the darkly comedic saga of a white trash clan in Texas getting into all sorts of trouble when a hitman (Matthew McConaughey) is hired to kill the family matriarch (Gina Gershon). The opening scenes are rather dull and formless, but the film gains momentum as it advances, and contains impressive performances by McConaughey and Juno Temple as a pre-teen girl with whom the hitman, being a pervert as well as a sociopath, becomes besotted. The screenwriter was Tracy Letts, who also did the honors on BUG, and who once again provides a fitfully perverse compendium of sleaze and bad behavior, complete with a delirious climax that contains one of the most outrageously offensive scenes—involving Gershon fellating a chicken wing(!)—of any movie ever made.

7. THE BIRTHDAY PARTY

This would appear to be Friedkin’s least characteristic concoction: a highly stagey British art film, adapted from an absurdist drama by Harold Pinter. Yet upon close examination THE BIRTHDAY PARTY, about a young man (Robert Shaw) harassed by a pair of ominous creeps (Patrick Magee and Sydney Tafler) in a British boarding house, contains more than its share of Friedkin-esque touches. The odd camera angles are quite characteristic, as is the atmosphere of mounting unease that suggests a stylistic forerunner to BUG. There’s also a blind man’s bluff sequence involving darkness and screams that’s as horrific as anything in THE EXORCIST, and a sense of homosexual panic whose apotheosis was reached in CRUISING. Friedkin never overcomes the inherent staginess of the material or its deeply elliptical gist, and nor does he try to, which depending on one’s pint of view can serve as a recommendation or a warning.

8. CRUISING

This 1980 flop is worthwhile, but I’m not convinced it’s the neglected masterpiece many folks have been proclaiming it. Al Pacino headlines as a cop going undercover in NYC’s gay S&M scene in search of a murderer. Friedkin’s portrayal of this subculture was apparently quite accurate, making the film something of a historical document. But CRUISING also works as a nasty, grungy thriller. Pacino is quite engaging, and chilling in the final scenes, in which it’s suggested (though never confirmed) that he may be the killer. The proceedings, alas, are cluttered and unfocused, with Pacino taking nearly 20 minutes to make his debut appearance in the film, and then periodically disappearing for long stretches.

9. RAMPAGE

A serial killer drama, initially completed in 1987, that was made under the auspices of the late De Laurentiis Entertainment Group, which lacked the funds to mount a proper release. Thus RAMPAGE remained undistributed in the US until 1992, with Miramax ultimately doing the honors. The film exists in two different cuts, the 97 minute DEG version from ‘87 and the 1992 Miramax one (from which Friedkin removed 10 minutes), both of which are disappointing. A large part of the problem, I’d opine, was with the fact that when it was made Friedkin was coming off a handful of TV projects, which explains why RAMPAGE looks and feels like a 1980s TV movie (with DEG’s habitual cost-cutting being another likely culprit). Inspired by the 1977-78 doings of the “vampire killer” Richard Trenton Chase, it’s about a suave serial killer (Alex McArthur) caught by police after slaughtering two families; an impassioned district attorney (Michael Biehn) seeks the death penalty, but faces an uphill battle. Friedkin does his best to maintain interest (as in Reece’s thoroughly implausible third act escape from police custody, which exists solely to keep us awake), but the shoddy production values keep the viewer at a constant remove.

10. THE BRINK’S JOB

Friedkin’s 1978 follow-up to SORCERER was this dramatization of the 1950 Brinks Company hold-up, at the time the largest robbery in American history, followed by the largest criminal round-up in American history. Sounds like ideal Hurricane Billy material, at least if it were played straight—the opposite, in other words, of the comedic treatment that Friedkin for some unfathomable reason wreaked on the material. As his early bummers GOOD TIMES and THE NIGHT THEY RAIDED MINSKY’S (see below) proved, comedy was not Friedkin’s forte, and it certainly doesn’t help matters that he completely jettisoned the grittiness that was his trademark, offering in its place burnished lighting, fake-looking scenery and a wholly inappropriate cartoon-worthy score. The cast is strong, with Peter Falk, Gena Rowlands, Warren Oates, Paul Sorvino and Allan Garfield all doing their best to jump start this misconceived material, and there are some brilliantly staged scenes in the final third (such as a wide shot of police officers threatening innocent motorists at gunpoint) that provide a tantalizing glimpse of what could have been.

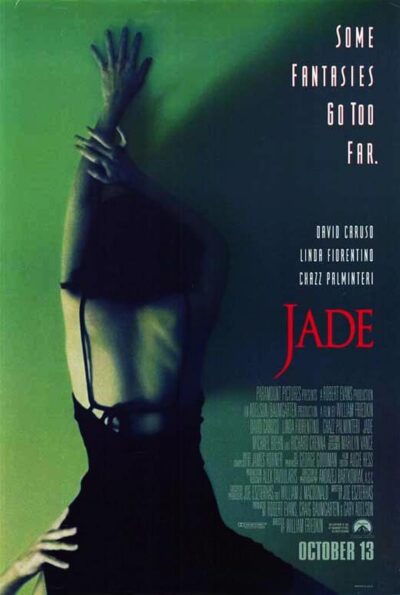

11. JADE

The nineties were a barren period for Friedkin, as evidenced by this ill-advised 1995 jump on the erotic thriller bandwagon. Yet Friedkin worked overtime, conjuring a powerfully brooding atmosphere and some bravura set-pieces, in particular a nerve-jangling car chase that inspires—and earns—comparisons with the classic auto menace sequence from Costa-Gavras’ Z (1969). Those things, alas, can’t overcome the altogether ludicrous script by Joe Eszterhas, once again mining the erotic thriller trope he invented in JAGGED EDGE (1985). As in that film, as well as BASIC INSTINCT (1992) and SLIVER (1993), we have a mild-mannered protagonist (David Caruso) amorously involved with a murder suspect (Linda Fiorentino) amid an avalanche of contrived intrigue. A director’s cut was released on VHS, but I haven’t seen it.

12. RULES OF ENGAGEMENT

A disappointing 2000 courtroom drama that was supposed to mark Friedkin’s comeback after a string of misfires. It starts out promisingly, with a Marine Colonel (Samuel L. Jackson) caught in the middle of a violent mob somewhere in the Middle East; eventually he gets fed up and, in a truly hair-raising sequence, orders his men to open fire on the crowd. For this he’s court-martialed and a gruff lawyer (Tommy Lee Jones) whose life Jackson once saved is called in to defend him—and the movie falls apart. Since Jackson is the hero we know he’ll win out in the end, despite his frankly questionable actions (a problem I also had with A TIME TO KILL, another Samuel L. headliner). Friedkin, in short, takes the predictable route early on and never deviates from it.

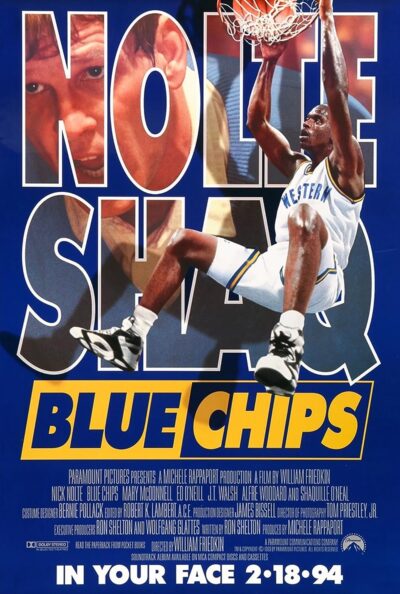

13. BLUE CHIPS

For this middling 1994 effort Friedkin (as he would with JADE) hitched himself to a prominent screenwriter, in this case sports guru Ron Shelton (best known for BULL DURHAM and WHITE MEN CAN’T JUMP). Featured is Nick Nolte as a college basketball coach who bribes players to join his team—whose ranks include Shaquille O’Neal as an impossibly virtuous draftee—and then feels guilty about it. In true Hollyweird fashion, Friedkin and Shelton try to have it both ways in a story that wants to function as an inspirational sports drama and a preachy message movie. Thus the film is a double fumble, with the game scenes failing to drum up much excitement (I wouldn’t dream of revealing whose team wins the climactic match) and the message, encapsulated in a pompous Nolte-delivered speech about the importance of ethics in sports, erring on the side of the painfully obvious.

14. THE GUARDIAN

In which Friedkin tried to recapture the magic of THE EXORCIST seventeen years later (note the opening credits font, which is identical to that of the previous film). He failed, due in no small part to the fact that THE GUARDIAN’s narrative, about a witchy nanny (Jenny Seagrove) who feeds babies to a sentient tree that likes to rip people apart with its branches, is even dumber than it sounds. Seagrove sets her sights on an LA couple (Dwier Brown and Carey Lowell) with a newborn infant Seagrove aims to make the tree’s latest victim, and ingratiates herself by seducing Brown–resulting in an eye-opening amount of nudity. The script (which was reportedly rewritten so much its primary author Stephen Volk had a nervous breakdown) diverts mightily from its source text, Dan Greenburg’s tight and compelling 1987 novel THE NANNY, and features one of the most unintentionally hilarious conclusions in horror movie history, with Brown taking a chainsaw to the tree, which bleeds real blood.

15. THE HUNTED

This 2003 actioner would seem to have everything going for it. The leading players Tommy Lee Jones and Benicio Del Toro are great actors, the cinematographer Caleb Deschanel is a world class talent, and the ultra-lean narrative was, appropriately for a chase thriller, stripped down to its bare essentials. Yet this unerringly slick, glitzy production never quite comes together. The problem seems to be that Friedkin and his collaborators were just too Hollywood-oriented, which lessens the impact of material the 1970s-era Friedkin could have really done something with. Tommy Lee is a Special Forces warfare instructor and Benicio a pupil who’s gone nuts, resulting in Jones chasing Del Toro, capturing him and then chasing him again. Not entirely unexciting, but the material needs a rawer treatment.

16. THE DEVIL AND FATHER AMORTH

It seems appropriate that the final film made by Friedkin, who began his career with documentaries, was a documentary—and an extremely low rent one, with the tawdriness decreed, supposedly, by its subject, a 91-year-old Italian priest who allowed Friedkin to document an actual exorcism, but only with the barest possible means. Yes, with this 69 minute film Friedkin directly harkened back to his most famous work, and in so doing examined his own feelings about faith and the devil. The resulting gabfest is extremely dull, with a lot of chatter about the reality of the exorcism we’re shown, consisting of Father Amorth chanting Biblical incantations at a woman who screams in a demonic voice while relatives hold her down. There’s no resolution, as Amorth dies before the afflicted woman is properly exorcised, leaving us with an awkward coda by Friedkin, who assures us “there is a far deeper dimension to the universe.”

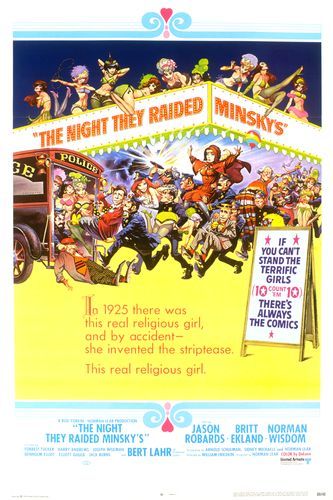

17. THE NIGHT THEY RAIDED MINSKY’S

Friedkin was still finding his way when he directed this 1968 big studio period piece (which, to continue the Francis Ford Coppola comparison made at the beginning of this article, was for Friedkin what the same year’s FINIAN’S RAINBOW was for Coppola). The film, with its handheld camerawork and kinetic editing, represents an early attempt at conjuring the raw immediacy of THE FRENCH CONNECTION, but (if the film’s editor Ralph Rosenblum is to be believed) Friedkin wasn’t too invested in his job. The setting is New York’s Minsky Burlesque show, circa 1925, where a young Amish woman (Britt Ekland) is looking to become a dancer and, due to a highly involved series of contrivances, ends up unwittingly inventing the strip tease. Once again a good cast was assembled—Jason Robards, Forrest Tucker, Denholm Elliott, Elliott Gould—and once again that cast was wasted.

18. THE BOYS IN THE BAND

Essentially a remake of THE BIRTHDAY PARTY: a stage-based drama about a party that goes horrifically wrong, in which the homosexual overtones of the earlier film were made quite overt. This film was a groundbreaker in its day, but now feels obvious and caricatured, not to mention extremely stereotypical in its portrayal of gay life; THE BOYS IN THE BAND doesn’t get mentioned much in discussions of queer cinema (in which arena CRUSING is more widely admired), and there’s a reason for that. Another problem is the punishing two hour runtime, which is much, much too long (for a much better dark-hued depiction of gay life that appeared around the same time as this film read the novel THE REAL THING, which would have made for an excellent William Friedkin film—we can only dream).

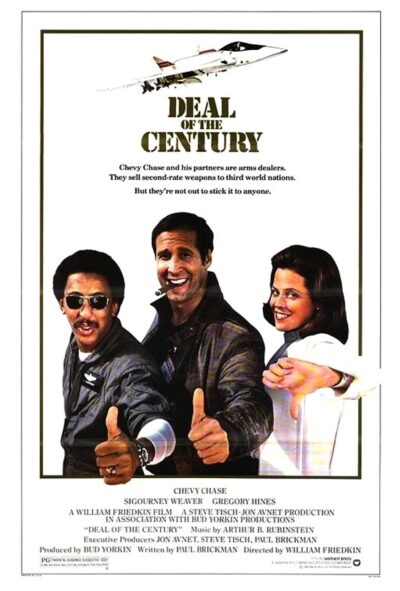

19. DEAL OF THE CENTURY

There’s no excuse for this 1983 bummer, an attempt at Strangelovian black comedy scripted by Paul Brickman (of CITIZEN’S BAND and RISKY BUSINESS) and starring Chevy Chase, Sigourney Weaver and Gregory Hines. Chase, playing an unscrupulous arms dealer getting involved with the sale of an experimental warplane, gets shockingly little to do, with the botched editing that afflicted so many Friedkin films being especially damaging here. The best bit involves Hines taking a flame thrower to a punk’s car after the latter threatens him, and repeating that he’s giving the vehicle “a little touch-up” (intended, no doubt, to become a hip catch-phrase). I haven’t gone into the special effects, and maybe I shouldn’t, as they’re lousy even by 1980s standards.

20. GOOD TIMES

Sonny and Cher’s only movie together, and, unsurprisingly, an appalling mess. The fact that Friedkin managed to find work after directing this fiasco (his feature debut) proves he was some kind of genius, as it represents the absolute dregs of late sixties “with it” bullcrap. Decked out in the expected gaudy décor, it features S & C “playing themselves.” They get offered a movie role and Sonny daydreams himself starring in a goofy western, a goofy jungle picture and a goofy film noir. It’s packed with embarrassing musical numbers notable for the fact that Cher and Sonny, both looking incredibly bored (and/or stoned), manage to somehow stay awake, something that probably can’t be said for the viewer.