Gennadiy Tishchenko may not be a household name, but it is an auspicious one in the field of Soviet science fiction. Born in 1948, the man was known as a prolific writer and painter until the well-received 1985 release of his student diploma film, the animated short FROM THE DIARIES OF IJON TICKY: A VOYAGE TO INTEROPIA (Iz dnevnikov Yona Tikhogo. Puteshestvie na Interopiyu), an adaptation of one of Stanislaw Lem’s popular Ijon Tichy stories. From then on animation became Tishchenko’s major focus.

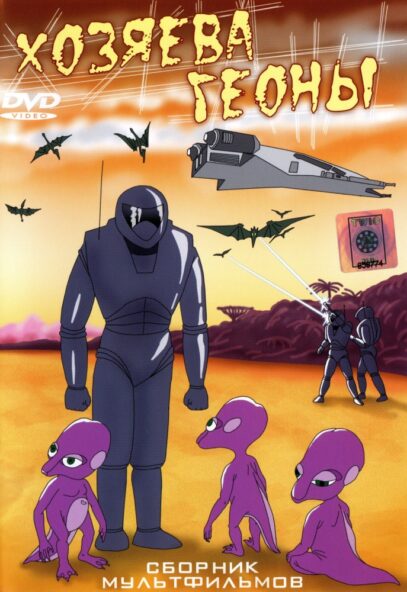

To date Tishchenko has made over a dozen animated shorts, four of them of particular interest: GEONA’S VAMPIRES (Vampiry Geony; 1991), MASTERS OF GEONA (Hozyaeva Geony; 1992), AMBA—FIRST MOVIE (Amba—Film pervyy; 1994) and AMBA—SECOND MOVIE (Amba—Film vtoroy; 1995). None are exceptional, but taken as a whole this quartet constitutes the most successful of Tishchenko’s filmic endeavors (others include 1989’s ALIEN MISSION/Missiya prisheltsev and 1990’s WHY CHICKENS DON’T PECK AT MONEY/Pochemu deneg kury ne klyuyut), being unashamedly adult efforts that spun serious sci fi tinged narratives, and did so at a time when the popularity of science fiction, which had taken Russia by storm in the 1980s, was on the wane.

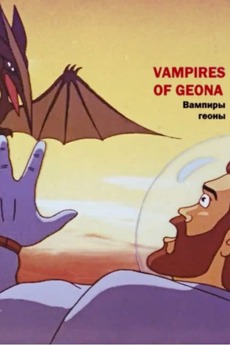

The ten minute GEONA’S VAMPIRES showcased an alternately pulpy and intellectual sensibility that evidenced a variety of influences, including Harry Harrison’s DEATHWORLD trilogy (and its 1980s Russian language follow-ups), FANTASTIC PLANET, ALIEN and THE MYSTERY OF THE THIRD PLANET, surely the gold standard of late Twentieth Century animated sci fi. If Tishchenko never quite reached the heights of the latter film’s creator Roman Kachanov, or those of the incomparable Vladimir Tarasov (of CONTRACT and THE PATH), it wasn’t for lack of trying. Furthermore, Tishchenko had an attribute his fellows didn’t: he used his artistic skills to personally design the visuals of his films, making him a rare example of an animation auteur.

In GEONA’S VAMPIRES a future government is attempting to establish a human colony on the treacherous planet Geona. The eponymous “vampires” are pterodactyl-like flying critters that cause deadly mutations. A red bearded inspector is tasked with scoping out the planet and providing a comprehensive report on the vamps. Upon landing on the surface, alas, the guy gets bitten by one of the critters and undergoes horrific hallucinations involving webbed fingers and growths sprouting from his body; luckily a doctor who resembles one Arnold Schwarzenegger (which was reportedly intentional on the part of Tishchenko) provides a life-saving antidote. The inspector goes on to half-heartedly oversee a massacre of the vamps, with a Sylvester Stallone lookalike (which was likewise said to be intentional) among the designated exterminators.

It’s an enjoyable film, action-packed and featuring some bizarre Rene Laloux-worthy imagery. The low budget hand drawn animation is decent, and there’s even a hint of an ecological conscience. Ultimately, though, GEONA’S VAMPIRES doesn’t work by itself, functioning as a promising set-up that’s paid off in the follow-up film.

MASTERS OF GEONA returns to the protagonist of part one, who’s now attempting to survive in the hostile environment of Geona. Having been bitten (again) by one of the pterodactyl-vamps, the inspector finds himself in the sights of some weird purple critters while a spaceship-bound detachment of humans, led by the aforementioned Stallone and Schwarzenegger clones, race to save his life. Spoiler alert: the inspector is saved, and concludes that the intercession of humans into Geona has irreparably altered the planet’s ecological balance, meaning they’d best leave.

The real-world themes hinted at in GEONA’S VAMPIRES are given a full airing in MASTERS OF GEONA. Also featured is a much greater plethora of otherworldly weirdness and a more confident use of animation. It nonetheless requires the set-up of its predecessor to be fully comprehended, meaning the two films should really be taken as a single twenty minute work (FYI, beware the English subtitled version currently blighting the internet, as those subtitles consist largely of smart-assed sex talk that from what I’ve been able to discern isn’t part of the original dialogue).

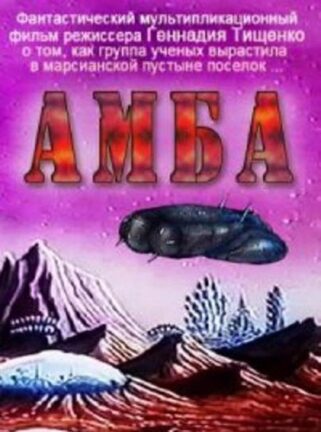

AMBA—FIRST MOVIE continues the quality progression. It has no direct relation to the GEONA films, but is thematically linked. FYI, AMBA and its sequel originated as parts of a feature-length whole entitled STAR WORLD, but the film (as was often the case with Tishchenko’s projects) was never completed. What we’re left with is a ten minute oddity that’s scant but still quite ambitious, indeed far more so the GEONA films.

The setting is once again a hostile planet. An experimental program called Amba (AutoMorphic Bioarchitectural Assemblage) has created a complex biosphere on the planet, an uninhabitable environ known as Mira. Amba is controlled by the brain of Rex, a dog that was severely injured saving his young master, Julia, in an accident. Rex’s owner Harper oversaw the creation of Amba, and used Rex’s brain in order to keep the dog’s essence alive—and also because of Rex’s ingrained sense of loyalty. As it happens, a Julia-led expedition to discern Amba’s progress is launched, and upon reaching Mira’s surface it’s resolved that things don’t look too good.

Once again, the film ends on an unresolved note, serving as, once again, a prolonged set-up rather than a standalone whole. It is nonetheless impressively visualized: the animation is striking and confident, without the low budget feel of the earlier films. On the downside, the human characters (Julia aside) are complete nonentities (if the bland white-skinned protagonists were given names I didn’t catch them).

AMBA—SECOND MOVIE has Julia and her companions exploring the surface of Mira, where they’re pulled into an underground cavern by tentacles controlled by Rex. The latter’s consciousness, represented by a godlike voice, has expanded exponentially, and developed supernatural powers in the bargain. Among other miraculous acts, Rex has transformed Harper, who like Rex himself was near death, into an octopus man. Rex, alas, was unable to stop corrosive mutations from overtaking the Amba and turning the planet into a mighty dangerous place, but he’s working to rectify the situation and create a more welcoming world.

Thus the AMBA mini-saga ends on a hopeful note, with the wonders of scientific potential emphasized in a manner that harkens back to Soviet made science fiction of the early-to-mid Twentieth Century. The fecundity of the imagery, however, is very much a late Twentieth Century addition, with monsters and mutation being constants. Equally striking is the intellectual conscience on display; this is science fiction as it should be presented, with mind-tugging speculative concepts being the major draw, and the imagery, striking though it is, taking a backseat.