Compiling a list of Ukrainian horror movies, much less essential Ukrainian horror movies, is no easy task. As always with my “Essentials” overviews, I’ve tried to be strict in my definition of horror, meaning horrific non-horror films from Ukraine like the 1990 Chernobyl dramatization DECAY (Raspad) and the 1991 historical saga FAMINE ‘33 (Holod 33) were left off—likewise post-millennial attempts at horror filmmaking such as the teen slasher fest THE PIT (Shtolnya; 2006) and the TWILIGHT ZONE-ish REJECTION (Ottorzhenie; 2011), as they’re far from essential.

Rather, I’ve turned my attention to the Ukrainian poetic cinema movement, which can be viewed as the country’s major cinematic innovation. I’ve also included some animated shorts, a format in which Ukraine has always excelled.

In the category of Ukrainian poetic cinema, whose emphasis was on image-based non-linear filmmaking, the late Yuri Ilyenko (often identified as Ukraine’s greatest filmmaker) was a key figure. His debut feature A SPRING FOR THE THIRSTY (Krynytsya dlya sprahlykh; 1965) remains an impressive example of the format (so too the same year’s Sergei Paradjanov helmed SHADOWS OF FORGOTTEN ANCESTORS, on which Ilyenko worked as a cinematographer), as does THE EVE OF IVAN KUPALO (Vecher nakanune Ivana Kupala), Ilyenko’s 1968 follow-up.

Working (as he always did) as his own cinematographer, Ilyenko provides a phantasmagoric recounting of an 1830 story by the Ukraine-born Nikolai Gogol. It features the lovesick young farmhand Piotr (Boris Khmelnitskiy) going mad after making a deal with the devil in a futile effort at winning the heart of the lovely Pidorka (Larisa Kadochnikova). This results in a wealth of amazing surreal images, contained in a wildly fragmented and chaotic whole. Clarity is something for which Ilyenko had little use, but his eye for evocative visuals, and sheer creative exuberance, results in a quintessentially Eastern example of gothic surrealism.

From there we jump forward two decades to THE WITCH (Vidma; 1990), which can almost be viewed as a sequel to the previous film (while the 1992 Natalya Motuzko directed GOLOS TRAVY feels like a follow-up to this one). Adapted from the 1833 novel THE KONOTOP WOTCH by Grigory Fedorovich Kvitka-Osnovyanenko, THE WITCH was directed by Galina Shigayeva, who has a pictorial aptitude nearly equal to that of Yuri Ilyenko (and no wonder, as Shigayeva was working for him at the time this film was made).

The setting is a rural village, circa the mid-1800s, whose corpulent military commander, or centurion (Bogdan Mikhailovich), tryies in vain to woo the angelic Olena (Halyna Kovhanych). She, together with several fellow witches from a neighboring tribe, responds to the centurion’s advances by finding various ways to string the guy along (and/or make an ass of him).

This is a film that, as with IVAN KUPALO, works in fits and starts, with moments of surreal brilliance offset by extremely erratic pacing and dumb-assed comedy (the sight of guys’ mustaches twisting upward to signify sexual arousal is about as funny as it sounds). On those occasions when the film works, though, it works supremely well.

I said I’d include some animated shorts in this listing, and FRIGHT MUZZLES (Strasti-mordasti; 1991), which emerged amid the cynicism and uncertainty that accompanied the collapse of the Soviet Union, makes for an excellent introduction to that format. A ten minute long anthology featuring a trio of horror themed mini-films, each made by a different director, FRIGHT MUZZLES adroitly showcases the stylistic range of Ukrainian animation while providing a potent three-tiered dose of no-frills horror.

The first segment, the Vladimir Goncharov directed “Escape,” is a stop motion oddity involving sentient meat in a kitchen, pursued by malevolent gloves and silverware seeking to slice it up; reminiscent of Jan Svankmajer at his grimmest, it’s a bleak and bloody spectacle with a hint of pitch-black humor. The highly impressionistic “Guest,” directed by Vadim Tyuryaev and Aleksander Bubnov, is about a horrific post-apocalyptic landscape in which not everything—or everyone—is what it seems. Lastly, the Valeriy Konoplev helmed “Kolobok” involves a mass of dough, intended as dinner for a pair of decrepit old men, rolling into the countryside and devouring everything in sight.

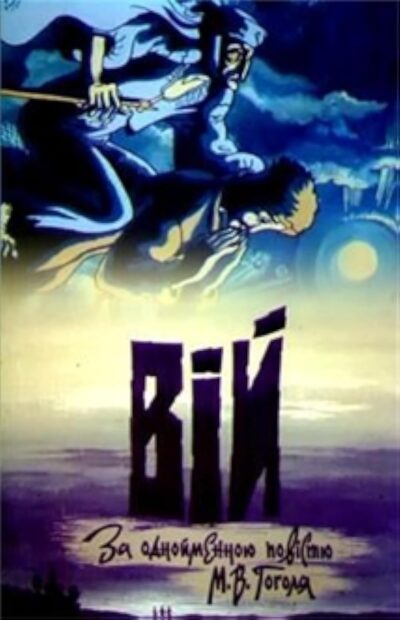

For the final entry in this overview I’ll turn once again to the field of animation, and the pivotal figure of Nikolai Gogol. His 1835 tale “Viy,” which is often credited as the first-ever vampire story, has been the source for some great films (BLACK SUNDAY, VIY) and some lousy ones (THE POWER OF FEAR, FORBIDDEN EMPIRE). The 1996 animated telefilm VIY [ВIй] thankfully hews closer to the former category. It’s certainly the screen’s most faithful transposition of the text, and the only adaptation of Gogol’s story to hail from the nation he called home.

Done in hand-drawn animation that recalls the glory days of Soviet cartooning, the pic is framed by two guys recounting the story’s particulars in a pub (a device that helps paper over the story’s boring passages). It relates the travails of Thomas, a naive seminary student.

The madness beings when during a nighttime trudge Thomas is harassed by an old witch, for whom he’s forced to serve as a mount. The poor guy is harassed even further when he’s chosen to watch over the witch’s cadaver for three nights, a task that becomes quite an ordeal. The corpse has a tendency to sit up and float around in its coffin, and on the third night summon a retinue of horrific creatures that include snakes, bats and the gnome king Viy, a furry creep with very (as in very-very) long eyelashes. That latter portion could admittedly have been a bit livelier (especially in light of the bravura of the equivalent sequence in the 1967 feature-length VIY), but otherwise I feel this film does its source material, and its author, proud.