It must have seemed like a good idea back in 1973: a TV series in the form of an epic space opera, fronted by two 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY alumni and two acclaimed science fiction writers working behind the scenes. Of those figures, alas, one of them happened to be perhaps the most cantankerous individual in science fiction history, who made sure to make his feelings about his employment known to anyone who would (or wouldn’t) listen. Even worse, the show in question was THE STARLOST.

It must have seemed like a good idea back in 1973: a TV series in the form of an epic space opera, fronted by two 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY alumni and two acclaimed science fiction writers working behind the scenes. Of those figures, alas, one of them happened to be perhaps the most cantankerous individual in science fiction history, who made sure to make his feelings about his employment known to anyone who would (or wouldn’t) listen. Even worse, the show in question was THE STARLOST.

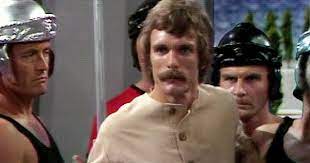

This 16 episode program is, quite simply, a travesty. It stars 2001’s Keir Dullea as a man living on what he thinks is an Earth-bound farm under the rule of an Amish-like cult headed by Sterling Hayden. But, as Dullea discovers upon being ousted from his community and entering a sliding door, he’s actually residing aboard a vast spaceship known as the Ark, launched from a dying Earth hundreds of years earlier. Even worse, Dullea learns that the Ark is on a collision course with an asteroid; clearly he’ll have to find some way to warn the other inhabitants about the coming disaster.

Dullea as a man living on what he thinks is an Earth-bound farm under the rule of an Amish-like cult headed by Sterling Hayden. But, as Dullea discovers upon being ousted from his community and entering a sliding door, he’s actually residing aboard a vast spaceship known as the Ark, launched from a dying Earth hundreds of years earlier. Even worse, Dullea learns that the Ark is on a collision course with an asteroid; clearly he’ll have to find some way to warn the other inhabitants about the coming disaster.

The filmmakers make their first major mistake in the opening minutes of the pilot episode, scripted by “Cordwainer Bird”—the pen name of the one and only Harlan Ellison—when they reveal that the whole thing is set aboard a spaceship, thus deflating the tension Ellison was attempting to build. Their second big mistake occurs at the end of the pilot, when Dullea and his pals happen upon the Ark’s control room (something Ellison intended them to do in the final episode.) From there Dullea and his pals become enforcers of a sort, travelling to the various parts of the Ark—one is decked out like Ancient Rome, another controlled by Walter Koenig as an alien, another afflicted by giant bees, etc.—and righting wrongs. It all ends with a whimper, never satisfactorily explaining the many enigmas that have been brought up or rounding out the character arcs.

Another important player in this series (initially at least) was Douglas Trumbull, 2001’s special effects ace. Trumbull came on board as special effects supervisor and executive producer, but left before shooting got underway, as did the scientific advisor Ben Bova, defections I fully understand; I haven’t even gone into the shitty “special” effects (redolent of those of SPACE: 1999), cheesy video stock and frequent bad acting that made this series a constant chore to watch.

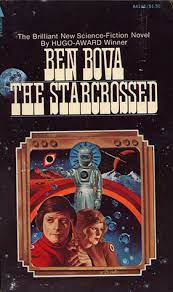

Ratings for the program were as you’d expect (terrible), resulting in NBC not picking it up for a second season. In the ensuing years THE STARLOST has become known more for the behind-the-scenes anecdotes of its production than what ended up on onscreen. Most of those anecdotes come from Ellison, who detailed his grievances in the essay “Somehow, I don’t Think We’re in Kansas, Toto” and a lengthy radio interview (published on YouTube). Yet Ben Bova, who left the show due to his frustration with terms like “radiation sickness” and “solar sun,” also wrote fairly extensively about the program in the form of a 1974 editorial in Analog magazine and a 1975 novel entitled THE STARCROSSED.

Ratings for the program were as you’d expect (terrible), resulting in NBC not picking it up for a second season. In the ensuing years THE STARLOST has become known more for the behind-the-scenes anecdotes of its production than what ended up on onscreen. Most of those anecdotes come from Ellison, who detailed his grievances in the essay “Somehow, I don’t Think We’re in Kansas, Toto” and a lengthy radio interview (published on YouTube). Yet Ben Bova, who left the show due to his frustration with terms like “radiation sickness” and “solar sun,” also wrote fairly extensively about the program in the form of a 1974 editorial in Analog magazine and a 1975 novel entitled THE STARCROSSED.

The latter relates the events of THE STARLOST’S production in the form of a satiric science fiction narrative dominated in large part by one Ron Gabriel, a short-tempered, foul-mouthed writer—and thinly-veiled stand-in for Harlan Ellison (another can be found in Herbert Kastle’s 1968 potboiler THE MOVIE MAKER). The events described in THE STARCROSSED were exaggerated, and given futuristic shadings (as in a party whose guests assume the holographic guises of various famous folk), but its descriptions of scripting duties being farmed out to high school students, Gabriel falling in love with the show’s seductive female lead and getting into fistfights with the higher-ups aren’t too far from the truth of what occurred during the production of THE STARLOST.

The first of its behind-the-scenes problems was with the “Magicam” system. An innovation developed by Douglas Trumbull, Magicam purported to allow the simultaneous filming and integration of live action foregrounds with special effects backdrops. The system, however, didn’t work out, forcing the production to make do with old school blue screen effects and the defection of Trumbull (who, for the record, would return with further innovations, including the ultra-expensive Showscan exhibition format, which didn’t go much further than Magicam).

From there the production devolved into a showdown between Ellison and a retinue of SF illiterate, corner-cutting moneymen. In fairness, Ellison had troubles with most of the TV series for which he wrote, having tantrumed at length over his treatment on THE OUTER LIMITS, STAR TREK and the eighties TWILIGHT ZONE reboot, but here I think his complaints were on target.

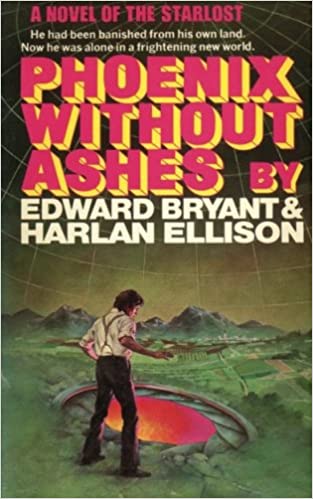

In “Somehow, I don’t Think We’re in Kansas, Toto” (initially published as the introduction to the PHOENIX WITH ASHES novel and then expanded for the collections STALKING THE NIGHTMARE and THE ESSENTIAL ELLISON), Ellison recounts how the program was conceived as a prestigious BBC series but ended up being made, far more cheaply, in Canada. There he was called upon to supervise an inexperienced writing crew, as a WGA strike and Canadian filming rules prevented him from doing much of the writing himself. This led to threats, intimidation and the sending of a beautiful actress to Ellison’s house by 20th Century Fox executive Robert Kline in order to sway him. Ellison quit before the filming of THE STARLOST’S first episode, walking away from a reported $93,000 (Ellison claims he told Kline “It’s worth ninety-three thousand bucks to see you fuckers go down the toilet”). His teleplay for the pilot episode, at least, won the 1974 WGA award for Most Outstanding Film/TV Screenplay, leading Ellison to state, during his acceptance speech, “If the fuckers want to rewrite you…smash them!”

the introduction to the PHOENIX WITH ASHES novel and then expanded for the collections STALKING THE NIGHTMARE and THE ESSENTIAL ELLISON), Ellison recounts how the program was conceived as a prestigious BBC series but ended up being made, far more cheaply, in Canada. There he was called upon to supervise an inexperienced writing crew, as a WGA strike and Canadian filming rules prevented him from doing much of the writing himself. This led to threats, intimidation and the sending of a beautiful actress to Ellison’s house by 20th Century Fox executive Robert Kline in order to sway him. Ellison quit before the filming of THE STARLOST’S first episode, walking away from a reported $93,000 (Ellison claims he told Kline “It’s worth ninety-three thousand bucks to see you fuckers go down the toilet”). His teleplay for the pilot episode, at least, won the 1974 WGA award for Most Outstanding Film/TV Screenplay, leading Ellison to state, during his acceptance speech, “If the fuckers want to rewrite you…smash them!”

Ellison’s original script, entitled “Phoenix Without Ashes” (changed to “Voyage of Discovery” onscreen) eventually saw publication in volume two of Ellison’s BRAIN MOVIES series. It was novelized in 1975 by the late Edward Bryant, who was known primarily for his short stories and book reviews. PHOENIX was one of Bryant’s rare long-form works of fiction, and provided a tantalizing glimpse of what we missed out on in the rest of his oeuvre. It’s lively and well written, and, needless to add,  far superior to its TV counterpart, being more imaginatively plotted (with the protagonist Devon finding a metal portal into which he falls a far more interesting artistic choice than the series’ doorway into which he walks) and just better in every respect. The novel’s major flaw is that, simply, it’s incomplete, novelizing only the open-ended pilot episode.

far superior to its TV counterpart, being more imaginatively plotted (with the protagonist Devon finding a metal portal into which he falls a far more interesting artistic choice than the series’ doorway into which he walks) and just better in every respect. The novel’s major flaw is that, simply, it’s incomplete, novelizing only the open-ended pilot episode.

Ellison dramatized PHOENIX WITHOUT ASHES again in 2011, via a graphic novel illustrated by Alan Robinson. It’s a good looking work, particularly in its depiction of the Ark as a conglomeration of interconnected spheres (as opposed to the dome-littered craft shown in the series), but it doesn’t contain much that the Bryant novel didn’t. In fact, it’s considerably less potent than the novel, as Ellison and Robinson appear to have gone out of their way to simplify and condense the material, whereas Bryant quite effectively broadened it out. The PHOENIX WITHOUT ASHES graphic novel is, in any event, far preferable to anything in THE STARLOST, which after decades of obscurity was released on DVD in 2008 (and pirated on YouTube not long after). I say it should have remained obscure.