On October 3, 1983, at the end of the popular children’s program RÉCRÉ A2 (RECREATION A2) on France’s Antenne 2 (now France 2) channel, TÉLÉCHAT (TELE-CAT in English) premiered. It was a five minute show that spoofed TV newscasts via a universe of animal newsreaders and sentient objects, although TÉLÉCHAT’s true gist was far more abstract and surreal, warping an entire generation of French youngsters.

On October 3, 1983, at the end of the popular children’s program RÉCRÉ A2 (RECREATION A2) on France’s Antenne 2 (now France 2) channel, TÉLÉCHAT (TELE-CAT in English) premiered. It was a five minute show that spoofed TV newscasts via a universe of animal newsreaders and sentient objects, although TÉLÉCHAT’s true gist was far more abstract and surreal, warping an entire generation of French youngsters.

…warping an entire generation of French youngsters.

Its creators included the French provocateur Roland Topor and the Belgian duo Henri Xhonneux and Éric van Beuren. Topor was a society-bashing surrealist whose output included graphic art, plays (LEONARDO WAS RIGHT), novels (THE TENANT, JOKO’S ANNIVERSARY), film design (FANTASTIC PLANET) and acting (Werner Herzog’s NOSFERATU); Xhonneux was known for directing the pioneering Belgian sexploiter TAKE ME, I’M OLD ENOUGH/ET MA SOEUR NE PENSE QU’ À ÇA (1970) and the comedy SOUVENIR OF GIBRALTER (1975); Van Beuren was a producer of SOUVENIR OF GIBRALTER and an executive producer of the animated comedy B.C. ROCK/LE CHAÎNON MANQUANT (1980). These three would go on to combine their talents for the 1989 puppet animation epic MARQUIS, a scandalous depiction of the Marquis de Sade as a dog headed libertine with a talking penis.

Before that, though, there was TÉLÉCHAT, designed by Topor, produced by van Beuren, and scripted by Topor and Xhonneux, who also directed every episode. Greenlit by Jacqueline Joubert, who oversaw Antenne 2’s youth unit, the program was a success, lasting a full three seasons (each of which contained 78 episodes). It is, nonetheless, exactly what you’d expect from a children’s program made by this infernal trio: weird, off-putting and often downright creepy.

It is, nonetheless, exactly what you’d expect from a children’s program made by this infernal trio: weird, off-putting and often downright creepy.

Its closest comparison is not another kids program, but rather LA MINUTE NECESSAIRE DE MONSIEUR CYCLOPEDE/THE NECESSARY MINUTE OF MR. CYCLOPEDE. That very adult-oriented program was a minute-long mock science show that, like TÉLÉCHAT, was added on to the end of other early 1980s programs and, also like TÉLÉCHAT, functioned as a spoof whose content tended toward the surreal.

Its closest comparison is not another kids program, but rather LA MINUTE NECESSAIRE DE MONSIEUR CYCLOPEDE/THE NECESSARY MINUTE OF MR. CYCLOPEDE. That very adult-oriented program was a minute-long mock science show that, like TÉLÉCHAT, was added on to the end of other early 1980s programs and, also like TÉLÉCHAT, functioned as a spoof whose content tended toward the surreal.

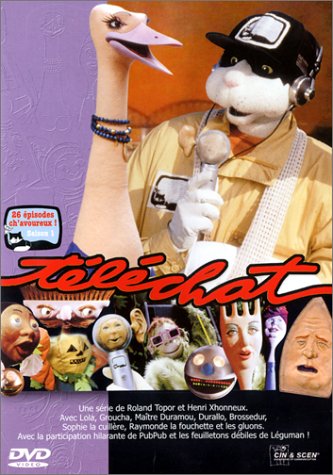

TÉLÉCHAT’s main players are a male cat and a female ostrich, who pontificate from a news desk. The cat has a cast on his left paw with a flap that when opened reveals itself as a container for all sorts of goodies, while the ostrich is constantly sticking her head in a hole in the desk. Other characters include an extremely chatty metal ball that resides in the hole in the desk, as well as a talking phone, microphone, fork, spoon and broom, each of which, in a quintessentially Toporian touch, has a face (and in the case of the microphone a large human ear).

The universe established in the first season of TÉLÉCHAT is one that includes a tape recorder that “plays” chocolate bars, a record player that runs on candy, and a “milk bar” in which, at the end of each episode, the protagonists are seen retiring. There’s also a green furred ape who supplies brief commercial breaks, and a show-within-the-show involving a pumpkin-headed individual presiding over a world of talking plants. All this, keep in mind, was contained in a show made, as Topor liked to claim, “by hand and with anchovy butter.”

All this, keep in mind, was contained in a show made, as Topor liked to claim, “by hand and with anchovy butter.”

Unfortunately the scripts don’t always do the visual ingenuity justice. Interesting conceptions, such as a performance of Hamlet with the title character represented by a cream pie(!), are breached but don’t really go anywhere, while the overarching narratives, which involve topics like the constantly fluctuating temperature in the studio and a viewer poll about the ideal paint color, tended to replicate the pointlessness of the real life newscasts Topor and co. were spoofing a bit too well.

Unfortunately the scripts don’t always do the visual ingenuity justice. Interesting conceptions, such as a performance of Hamlet with the title character represented by a cream pie(!), are breached but don’t really go anywhere, while the overarching narratives, which involve topics like the constantly fluctuating temperature in the studio and a viewer poll about the ideal paint color, tended to replicate the pointlessness of the real life newscasts Topor and co. were spoofing a bit too well.

The second season changed things up a bit. The preamble, which had previously consisted of a stuffed bear watching a TV monitor on the roof of a building, depicts a helicopter flying through an open window and into somebody’s living room. This presages a more generously budgeted treatment than was afforded the earlier season, with the puppet characters, joined by a talking lightbulb, frequently venturing outdoors amid a landscape that’s far grander and more elaborate than what came before.

The feline newsreader of season one was replaced, in the first fourteen episodes, with a talking rat wearing an oversized suit, but otherwise the particulars were kept largely the same, with a green ape still providing commercial breaks, the talking objects and pumpkin-head making frequent appearances, and the cat from season one turning up at the end of each episode, often in the milk bar from season one.

Then, in episode fifteen, the rodent newscaster appears heavily bandaged and, concluding that “nobody loves me anyway,” exits, with the cat once again assuming news reading duties alongside his ostrich partner (although the rat continues to make periodic appearances in the form of a roving reporter). And yes, you can rest assured that the subject matter, which includes invisible dogs that excrete very real urine, a garden that grows American hundred dollar bills, and a chaise lounge performing a “sacred dance,” is every bit as crazed as it previously was.

Then, in episode fifteen, the rodent newscaster appears heavily bandaged and, concluding that “nobody loves me anyway,” exits, with the cat once again assuming news reading duties alongside his ostrich partner (although the rat continues to make periodic appearances in the form of a roving reporter). And yes, you can rest assured that the subject matter, which includes invisible dogs that excrete very real urine, a garden that grows American hundred dollar bills, and a chaise lounge performing a “sacred dance,” is every bit as crazed as it previously was.

Season three had a new preamble, this one set in a fish tank where a submarine approaches a tiny TV monitor. The protagonists were given updated studios with art deco furnishings, although they don’t spend much time in that setting, with the show taking place largely outdoors, amid a talking car with eyes, a nose and a mustachioed mouth. Other newly minted sights include a waste bucket frog, winged clocks, ice skates that serve as record needles, shoeless socks that lead a secret life (they being an “aquatic species,” which explains “why they get wet in the shoes”) and a book with slices of ham in place of pages.

What hasn’t changed is the tiresomely nonsensical nature of the narratives—although Topor and co. were clearly aware of that fact, and evidently strove to enhance the nonsensicality. Certainly the aforementioned ham slice book was a direct reference to that fact, and its mere presence is a stern warning not to take anything herein too seriously. Kids, at least, seemed to get it.

See Also: