With cyberpunk making an unexpected comeback in 2020, a look back at the genre’s 1980s origins seems in order. Cyberpunk’s antecedents include William Gibson’s 1984 novel NEUROMANCER, the flicks BLADE RUNNER and THE TERMINATOR, and the 1987-88 TV series MAX HEADROOM. The latter is in many respects the most fascinating of the lot, a prime time television program that pivoted on a popular media personage. If ever a show shouldn’t have worked it was this one, yet somehow MAX HEADROOM emerged as one of the great American TV programs of the decade, and one of the purest distillations of cyberpunk’s overriding themes and attitudes.

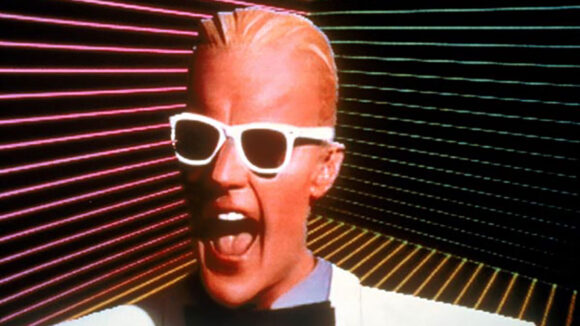

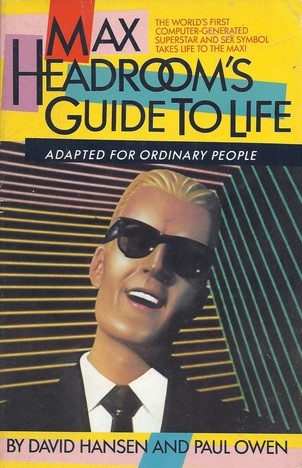

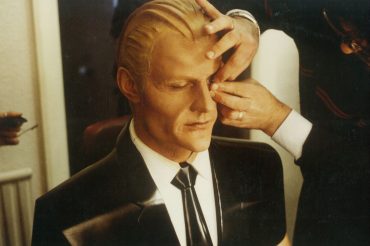

Max Headroom is an alleged computer hologram, but in actuality was actor Matt Frewer, ad-libbing a stream-of-consciousness mouthful of stuttering quips over an animated background. Said to be a major inspiration on the comedy of Jim Carrey, this personage began as a VJ on the UK’s channel four. THE MAX HEADROOM SHOW was created by the music video specialists Rocky Morton and Annabel Jankel, who also turned out an hour long TV movie comprised of footage intended for the program. That movie in turn inspired the American made MAX HEADROOM series, just as Max branched out in the form of a chat show, THE ORIGINAL MAX TALKING HEADROOM SHOW, which managed six episodes on Cinemax in 1987. There was also a trade paperback entitled MAX HEADROOM’S GUIDE TO LIFE, released in the UK in 1985 and in the US the following year.

Max Headroom is an alleged computer hologram, but in actuality was actor Matt Frewer, ad-libbing a stream-of-consciousness mouthful of stuttering quips over an animated background. Said to be a major inspiration on the comedy of Jim Carrey, this personage began as a VJ on the UK’s channel four. THE MAX HEADROOM SHOW was created by the music video specialists Rocky Morton and Annabel Jankel, who also turned out an hour long TV movie comprised of footage intended for the program. That movie in turn inspired the American made MAX HEADROOM series, just as Max branched out in the form of a chat show, THE ORIGINAL MAX TALKING HEADROOM SHOW, which managed six episodes on Cinemax in 1987. There was also a trade paperback entitled MAX HEADROOM’S GUIDE TO LIFE, released in the UK in 1985 and in the US the following year.

The latter, written by David Hansen and Paul Owen, purports to be an advice book by Max H. It includes quintessentially eighties  homilies like “Your style is the most important statement you can ever make about yourself” and “The first decision to make before you go anywhere to eat is not “What can I afford?” but “What mood am I in?”” It’s not unamusing, but Max Headroom’s charm is primarily visual in nature, and doesn’t really come off on the printed page.

homilies like “Your style is the most important statement you can ever make about yourself” and “The first decision to make before you go anywhere to eat is not “What can I afford?” but “What mood am I in?”” It’s not unamusing, but Max Headroom’s charm is primarily visual in nature, and doesn’t really come off on the printed page.

The MAX HEADROOM programs offer a much stronger representation of the character’s appeal. THE MAX HEADROOM SHOW features Max in his element, offering rambling, pun-laced introductions to music videos from bands like Ultravox, Pale Fountains and the Kinks. Things degenerated considerably, alas, once Max migrated to Cinemax: THE TALKING MAX HEADROOM SHOW was quite choppy, with music videos abruptly cutting in and out of interviews. As an interviewer Max was an incurable wise-ass, and wasn’t shy about goading his interviewees unmercifully, but as everyone involved was clearly taking the whole thing as a joke there wasn’t any real consequence. The show’s creators were evidently striving for late eighties hipness at all costs, which of course is no longer hip—although it is undeniably nostalgic.

Speaking of nostalgia, we mustn’t forget the endearingly ridiculous 40 minute MAX HEADROOM CHRISTMAS SPECIAL from 1986. It features Max on a TV monitor getting pelted with snowballs, chatting with celebrity guest stars like Tina Turner, Robin Williams and Bob Geldof, and warbling instantly forgettable holiday tunes.

As for the MAX HEADROOM movie, it’s something else entirely. It is, outside the now-archaic technological details, one the very few TV movies to emerge from the eighties that was truly ahead of its time—in fact, in many ways it’s still ahead. Directed by Max’s creators Rocky Morton and Annabel Jankel (who would go on to flame out rather spectacularly with the 1988 D.O.A. and 1993’s SUPER MARIO BROS.), it adroitly set the tone for the subsequent MAX HEADROOM series with its dizzying pace, eye catching visuals and innovative editing that juxtaposes live action and video footage.

Set in a BLADE RUNNER-esque future world in which 1940s-era architecture and machinery intersects with 1980s computer technology, the story concerns Edison Carter (Frewer), an ace TV reporter investigating “blipverts” put out by the monolithic Network 23. Blipverts are commercials that lodge themselves in people’s consciousness, and in doing so cause them to explode. Network 23’s corrupt bosses try to silence Carter, but a young computer whiz (Paul Spurrier) encodes his memories into a program called Max Headroom (named after a parking garage sign reading “MAX. HEADROOM: 2.3 M”), which somehow ends up in the hands of the pirate TV channel Bigtime, and proves a ratings hit—just as Edison manages to get himself up and running and, together with his sexy computer hacker assistant Theora (Amanda Pays), exposes the dastardly machinations of Network 23. It all adds up to a bizarre and  endlessly kinetic hour of television.

endlessly kinetic hour of television.

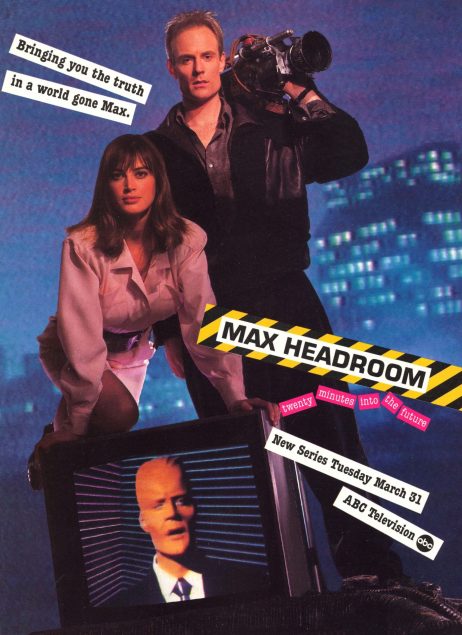

This brings us to what is in my view the apotheosis of the Max Headroom phenomenon: the two season, fourteen episode MAX HEADROOM TV Series, which ran on ABC, starting in the spring of ‘87 and concluding roughly a year later. The program may have been short-lived, but it remains one of the most innovative and slyly subversive American TV series of all time. Morton and Jankel had no involvement (Jankel claims to have never viewed a single episode), but the vision they imparted back in 1985 was carried through.

Set “Twenty Minutes in the Future”, the show commences with what is essentially a scene-by-scene redo of the preceding film. Frewer returns as Edison Carter and Max Headroom, as does Amanda Pays as Theora, with most of the rest of the roles recast. The series format allows more time to be lavished on concepts like the “electronic television matrix” (or, as it’s now known, the internet) in which Max Headroom resides, and the relationship between Edison and his computerized alter ego, who frequently play off each other.

The result is pure science fiction brilliance, done with a style and verve that remain distinct. The show’s lightning fast pacing and dead-on criticism of the TV business co-exist with innovative concepts like the aforementioned blipverts and second-by-second TV ratings that are monitored like football scores. There are also TV ads that cause viewers to grow addicted to their televisions, and others that imprint themselves directly onto viewers’ minds, threatening to render commercial television obsolete.

The show’s 1980s-era computer imagery is one area in which it’s admittedly grown quite dated. The central theme, however, of a sentient computer program becoming increasingly difficult for its creators to control, couldn’t be more relevant to our present world.

A major problem with MAX HEADROOM’s viewership, outside the obvious—namely the fact that TV viewers, despite claiming to want  new and innovative fare, tend to reject anything that’s truly new and innovative—was overexposure on the part of its title character. By 1988 Max Headroom was ubiquitous on television, as a Coca-Cola spokesperson and interview subject in addition to his roles as chat show host and TV star. There was also the incident of November 1987, when a still-unidentified someone wearing made up as Max Headroom hacked into a couple of Chicago television stations to spout gibberish and bear his ass, and the many imitations and parodies that popped up (who can forget “Maxine Legroom,” a.k.a. Sandy Greenberg, who graced Playboy’s January 1987 issue?).

new and innovative fare, tend to reject anything that’s truly new and innovative—was overexposure on the part of its title character. By 1988 Max Headroom was ubiquitous on television, as a Coca-Cola spokesperson and interview subject in addition to his roles as chat show host and TV star. There was also the incident of November 1987, when a still-unidentified someone wearing made up as Max Headroom hacked into a couple of Chicago television stations to spout gibberish and bear his ass, and the many imitations and parodies that popped up (who can forget “Maxine Legroom,” a.k.a. Sandy Greenberg, who graced Playboy’s January 1987 issue?).

Hence, in 1988 both MAX HEADROOM and the Max Headroom phenomenon came to an abrupt end. I’ll always miss the series, which I believe had a ways to go, with plenty of concepts and plot points that were eminently worthy of further exploration, but admittedly had my fill of Max H. Re-familiarizing myself with him, I find that his never-changing appearance and stuttering banter, witty and visually enticing though they are, tend to get old after about ten seconds.