Here’s an interesting program from the aughts, a spin-off of the popular Showtime/Anchor Bay anthology series MASTERS OF HORROR. That program, which ran from 2005-07, was created by Mick Garris, who gave several prominent genre directors (including John Carpenter, Don Coscarelli, Stuart Gordon, Joe Dante, Larry Gordon and John McNaughton) carte blanche to create hour-long horror fests. That the show only lasted two seasons was unjust, as it was quite popular, with its cancellation coming about due to a contract dispute between Showtime and Starz Entertainment (which took over Anchor Bay) rather than poor ratings (with a severely watered-down NBC spin-off called FEAR ITSELF serving as a third season).

Here’s an interesting program from the aughts, a spin-off of the popular Showtime/Anchor Bay anthology series MASTERS OF HORROR. That program, which ran from 2005-07, was created by Mick Garris, who gave several prominent genre directors (including John Carpenter, Don Coscarelli, Stuart Gordon, Joe Dante, Larry Gordon and John McNaughton) carte blanche to create hour-long horror fests. That the show only lasted two seasons was unjust, as it was quite popular, with its cancellation coming about due to a contract dispute between Showtime and Starz Entertainment (which took over Anchor Bay) rather than poor ratings (with a severely watered-down NBC spin-off called FEAR ITSELF serving as a third season).

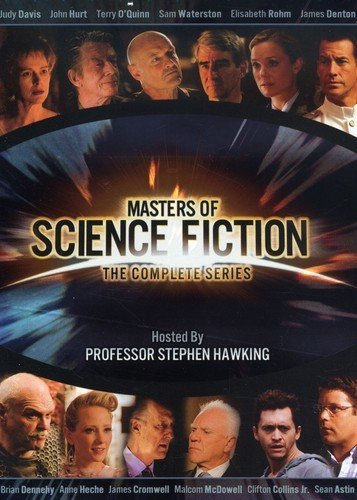

MASTERS OF SCIENCE FICTION appeared in 2007. It credited Garris as a “Co-Executive Producer,” although he claims to have had no direct involvement in the series. That explains the near-complete lack of publicity it received, which ran counter to MASTERS OF HORROR (which Garris, using his skills as a former Hollywood publicist, heavily promoted at horror conventions and in the pages of Fangoria). No surprise: the ratings for MASTERS OF SCIENCE FICTION were, in Garris’ words, “miserable.”

No surprise: the ratings for MASTERS OF SCIENCE FICTION were, in Garris’ words, “miserable.”

Another way in which this program differed markedly from MASTERS OF HORROR was that the “masters” in the latter case were the directors whose names graced the show, whereas here those masterful monikers were the authors of the stories being adapted, which included Robert Heinlein, Harlan Ellison and Robert Sheckley. Of course those adaptations were quite loose for the most part, and marred by all-too-evident corporate cost cutting.

“From the very beginning we have wondered how life began, what our purpose is and where we are headed. We have struggled to understand time, matter, the infinite universe, who we are, and if we are alone. Great minds have imagined the most wonderful, and most terrifying answers to these questions.” So claims the opening narration, spoken in the unmistakable computerized tones of the late Stephen Hawking, who served as the series’ Rod Serling.

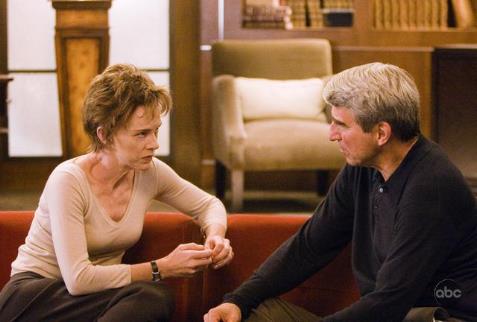

The premiere episode was “A Clean Escape,” based on a 1985 story by John Kessel. The director was the respected Hollywood veteran Mark Rydell, whose work ranges from good (THE REIVERS and the late period John Wayne vehicle THE COWBOYS) to lousy (INTERSECTION). “A Clean Escape,” to date Rydell’s final directorial credit, thankfully ranks in the former category.

Featured are two topflight actors: Judy Davis and Sam Waterston, with she playing a psychiatrist and he a man suffering severe amnesia. It’s her job to interrogate him, the reason for which takes until nearly the end to be fully revealed. We’re also not immediately informed precisely where this drama is taking place, although the troubling-yet-provocative answer turns out to be well worth the wait.

her job to interrogate him, the reason for which takes until nearly the end to be fully revealed. We’re also not immediately informed precisely where this drama is taking place, although the troubling-yet-provocative answer turns out to be well worth the wait.

Rydell keeps the suspense at full boil throughout, with several well integrated flashbacks and canny intercutting between Davis’ interrogation and the government superiors observing it. My only real complaint is with the distracting commercial breaks scattered throughout, which brings up another way in which this program diverges from MASTERS OF HORROR: it was made for network TV, and subject to its strictures.

My only real complaint is with the distracting commercial breaks scattered throughout, which brings up another way in which this program diverges from MASTERS OF HORROR: it was made for network TV, and subject to its strictures.

Episode two, “Awakening,” was inspired by the 1970 tale “The General Zapped An Angel” by Howard Fast. That story was about the shooting down of an angel during the Vietnam War, which was changed to a humanoid alien in the Gulf War. A retired major (Terry O’Quinn) is called in to deal with the critter, who communicates by taking over the bodies of the people surrounding it and making them recite pacifist platitudes.

Ignoring the simplicity of the Howard Fast text, the script adds several more alien ships massing around the world, all with a very definite agenda: to get humankind to dismantle its nuclear weapons. If we don’t do so they’ll blow us up, thus turning the story into an uninspired variant on THE DAY THE EARTH STOOD STILL—and as if that weren’t enough, there’s a regurgitation of the ever-popular dead relative trope that infects so many modern sci fi movies (see CONTACT, GRAVITY and ARRIVAL), with Quinn eventually meeting his deceased wife, who helps convince him of the aliens’ wisdom.

Ignoring the simplicity of the Howard Fast text, the script adds several more alien ships massing around the world, all with a very definite agenda: to get humankind to dismantle its nuclear weapons. If we don’t do so they’ll blow us up, thus turning the story into an uninspired variant on THE DAY THE EARTH STOOD STILL—and as if that weren’t enough, there’s a regurgitation of the ever-popular dead relative trope that infects so many modern sci fi movies (see CONTACT, GRAVITY and ARRIVAL), with Quinn eventually meeting his deceased wife, who helps convince him of the aliens’ wisdom.

Next up is “Jerry Was A Man,” based on a 1947 Robert Heinlein story that was adapted and directed by Neil Tolkien. Those familiar with the Tolkien scripted films THE PLAYER, THE RAPTURE and THE NEW AGE will recognize the satiric portrayal of a filthy rich couple (Anne Heche and Russell Porter) in a future Los Angeles who adopt a robot named Jerry (Jason Diablo) from a corporation headed by a sly CEO (Malcolm McDowell).

Unfortunately the resulting drama, which concludes with Jerry being put on trial to determine his humanity, is pretty dull. The questions it raises, about the vagaries of artificial intelligence and precisely how it differs from so-called human nature, have been asked before, and more provocatively, by authors like Philip K. Dick and Brian Aldiss—and also the films, such as BLADE RUNNER and A.I., adapted from their works, to which “Jerry Was A Man” has nothing worthwhile to add.

Episode 4, “The Discarded,” emerged from the pen of the late Harlan Ellison. Adapted by Ellison and Josh Olsen (Ellison’s right hand man during his final years), it was directed by STAR TREK: THE NEXT GENERATION’S Jonathan Frakes and boasts an impressive cast headed by John Hurt and Brian Dennehy. Hurt plays one of a spaceship-full of pandemic-afflicted human oddities who’ve been exiled from their home planet. When an emissary from Earth turns up on the ship a ray of hope would appear to be offered, with the guy promising to allow the Discarded back if they’ll be willing to give blood for the creation of a serum.

during his final years), it was directed by STAR TREK: THE NEXT GENERATION’S Jonathan Frakes and boasts an impressive cast headed by John Hurt and Brian Dennehy. Hurt plays one of a spaceship-full of pandemic-afflicted human oddities who’ve been exiled from their home planet. When an emissary from Earth turns up on the ship a ray of hope would appear to be offered, with the guy promising to allow the Discarded back if they’ll be willing to give blood for the creation of a serum.

Not a whole lot happens, with the episode taken up largely with the type of hard-boiled dialogue that tended to mark Ellison’s screenplays (“You’re their lapdog with a bad case of the mange!”). A major problem is the fact that the alleged freaks all look too normal, with an oversized arm sported by Dennehy and an extra head seen on Hurt’s right shoulder being the freakiest things we’re shown. Luckily the script captures the story’s blunt and unforgiving tenor, and also its overall message—which was, in its author’s own none-too-sanguine words, that “Pretty people have it easier than uglies.”

“Little Brother” was helmed by the prolific indie-film-queen-turned-journeyman-TV-director Darnell Martin, from a script by Donald Mosley that was based on his own short story of the same name. It’s about a once-unthinkable future justice system in which computer technology allows the suspect, the judge and the jury to interact from different venues (a zoom meeting, in other words). The fact that this future is no longer very futuristic explains in part why the episode isn’t too invigorating. It does, however, contain some interesting elements, including a courtroom with roving TV monitors that looks like something out of a Terry Gilliam movie and the addition of deceased jury members who are called up from the dead to decide the fate of a young punk (Clifton Collins, Jr.) accused of killing a cop.

Finally we have “Watchbird,” adapted from a story by Robert Sheckley. It’s about mechanical Watchbirds, invented by a mild-mannered computer nerd (Sean Astin), that can sense peoples’ murderous intent, and swoop down to stop the killings from being committed. Astin’s superior is essayed by James Cromwell, essentially repeating his slimy authoritarian role from LA CONFIDENTIAL, and the setting an early aughts cityscape.

Finally we have “Watchbird,” adapted from a story by Robert Sheckley. It’s about mechanical Watchbirds, invented by a mild-mannered computer nerd (Sean Astin), that can sense peoples’ murderous intent, and swoop down to stop the killings from being committed. Astin’s superior is essayed by James Cromwell, essentially repeating his slimy authoritarian role from LA CONFIDENTIAL, and the setting an early aughts cityscape.

The direction, by the thriller specialist Harold Becker (of THE ONION FIELD and SEA OF LOVE), is uninspired, and the script, by episodic TV veteran Sam Egan (of quite a few Glen Larson series), plays down the many provocative concepts brought up in the story (such as the birds’ targeting of hunters, fishermen, slaughterhouse workers, animals and eventually the Earth itself, because “No one had told the watchbirds that all life depends on carefully balanced murders”). In their place is a clichéd depiction of Astin and Cromwell arguing about the efficacy of their creation.

With so much mediocrity it’s no surprise MASTERS OF SCIENCE FICTION only lasted six episodes. Still, the good things contained in “A Clean Escape,” “The Discarded” and “Little Brother” prove that the show had promise, and could conceivably have gone the distance had only its makers—or, perhaps more accurately, its backers—tried a little harder.