In the category of insane asylum set TV programs the ten episode Norwegian miniseries MANIAC (not to be confused with the 1980 William Lustig slasher classic, nor the 2012 remake) is a definite standout. It aired in December 2015, and is best known nowadays (if at all) as the inspiration for the star-studded 2018 Netflix program of the same name (note how the imdb bios for the cast of the 2015 MANIAC take care to inform us that the show was “later picked up for a re-make by Netflix International”).

2015 Maniac Original

MANIAC TV Series (2015) Trailer

The title character is Espen, a delusional schizophrenic played by Espen Petrus Andersen Lervaag (who also co-scripted the series). Not unlike a more overtly psychotic THE SECRET LIFE OF WALTER MITTY, we see Espen’s delusions dramatized, with the actors playing the “real” roles assuming corresponding parts in the fantasy sequences—example: Espen fantasizing about mowing down Nazis with a machine gun when in reality he’s peeing on a row of cut-out paper figures tacked to a wall. In this way we’re made to see the true motivations of his actions, with his urinating on the paper cut-outs having sinister connotations and a later scene, in which he pulls the chair out from an orderly, being comparatively benign in intent. Also along for the ride is Espen’s fantasy pal Håkon (Håkon Bast Mossige, who likewise served as a co-scripter), who turns up in each of Espen’s delusions to reinforce his break with reality.

The series revolves around Espen’s evolving relationship with his attractive shrink Mina. The asylum’s overseers don’t think much of Espen, wanting to transfer him to the dreaded C (or solitary) ward, but Mina sees promise. He apparently reminds her of her deceased brother, who died when she was 15, and she also has a thing for Espen (despite the fact that’s he’s unattractive, overweight and insane).

In the premiere episode Espen fantasizes himself a superhero and Mina a seductive damsel in distress, while in episode two, when their real-life relationship starts to sour, he’s a heroic American soldier and she’s a Nazi. In episode three he’s a suave secret agent and in part four a Jerry Seinfeld-esque stand-up comedian (with fantasies that include twangy SEINFELD-inspired music). Episode five ups the outrage factor considerably, with Epson, possessed of a massive snake-like penis, running around the asylum sexually harassing female patients and assuming a new guise: that of a normal guy caught up in a Mina led zombie apocalypse. In episode six Epson becomes a suave secret agent involved in an elaborate heist, in episode seven he’s an autocratic movie director and Mina his star actress, and episode eight sees him as a teenaged jock and Mina an “ugly nerd” girl. Epsen plays a cowboy in episode nine, and in the final episode he’s released back into society after spending three months in C ward; all seems well until Epsen learns that Mina is set to be married to a man who isn’t him, and Håkon, who was seemingly killed in the previous episode, turns back up…

The intended spark to all this is the intercutting from the opulence of the fantasy sequences to the drabness of reality, but as staged by director Kjetil Indregard the scenery of the those fantasy sequences is shoddy and unconvincing. In episode seven, for instance, when Espen’s fantasy of being feted at an awards ceremony is intercut with a funeral he’s attending, the latter scenes, contrary to what was intended, are more visually compelling than the former ones. Ditto the western milieu of episode nine, which seems incongruous and unconvincing amid the rustic Norwegian scenery.

It’s the performance of Espen Petrus Andersen Lervaag that keeps things afloat. He’s equally compelling as an action hero, a sitcom star and a somewhat normal guy, and Angelina Jolie lookalike Ingeborg Raustøl nearly matches his work as Mina, who assumes just as many guises and more than holds her own in each.

That the series was made prior to the Me Too era is evident in the sexualizing of Ms. Raustøl, who appears in a number of skimpy outfits. This, of course, is consistent with Espen’s view of her, which is sexual above all else, and leads to him committing a number of inappropriate acts that she rather inexplicably forgives (she’s supposed to be in love with him, but again, that attraction is never too convincing). This lends a gravity that probably wasn’t present upon MANIAC’s initial 2015 airing, somewhat offsetting what in my view is the program’s most grievous flaw: the fact that it’s so lightweight, in both style and tone, it all but floats off the screen.

As such the proceedings are not suitable for an entire series (even a miniseries), as thematically there’s barely enough here for an eighty minute feature. This is a rare occasion in which a program’s Americanized redo actually outdoes its predecessor.

2018 Maniac Redo

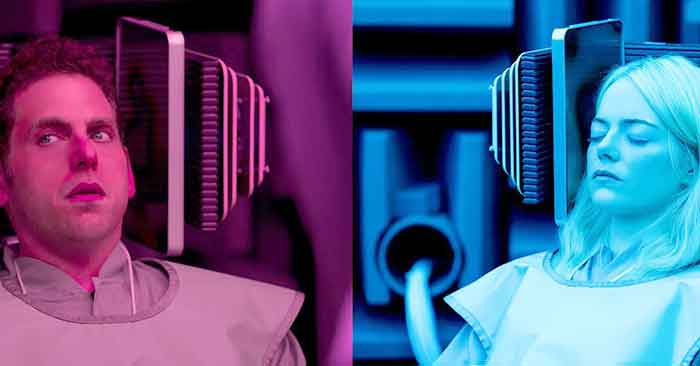

Regarding the 2018 redo, it took quite a few liberties with its source, starting with a science fiction wraparound. Jonah Hill and Emma Stone were charged with jointly essaying the title role, with he being a paranoid nut and she a bitter recluse haunted by the death of her sister in a car accident. The setting is a future America where a pharmaceutical company is testing a drug that promises to remove all traces of mental distress. Hill and Stone elect to take part in the experimental trial, which involves a virtual reality redo of one’s most unpleasant memory—but the computer overseeing the trial, patterned after the mind of a popular self-help author (Sally Field), malfunctions, stranding Hill, Stone and their fellow volunteers in a succession of fantasy worlds (a 1980s townscape, a LORD OF THE RINGS-inspired neverland, a 1940s cityscape) from which there’s no evident escape.

MANIAC Netflix Series (2018) Trailer

Director Cary Joji Fukunaga (BEASTS OF NO NATION) does a far better job than Kjetil Indregard did of visualizing the various levels of unreality encountered by his characters, inviting comparison with classic mindbenders like JE T’AIME, JE T’AIME and PROVIDENCE. The program’s one major flaw in my view is one that afflicted the earlier MANIAC: there’s just not enough here to fill a ten episode miniseries, resulting in an excess of superfluous characters and subplots (such as one involving Stone’s attempts at conning her way into the experimental trial and another about a sexual harassment suit brought against Hill’s brother). That explains, perhaps, why the series, despite its undeniable qualities, only managed a single season (whereas its makers apparently envisioned several).

The 2018 MANIAC fared better, at least, than the original, which hasn’t seen much play outside its initial airing. It was picked up for distribution by Netflix (and as of September 2019 can still be viewed in English subtitled form therein) but doesn’t appear to have made much of an impression. That’s a just state of affairs as, unique and ambitious though it is, the show frankly isn’t very good.