Filippe’s Vimeo Channel can be found HERE.

2019 marked the 20th anniversary of THE BLAIR WITCH PROJECT, but I say it’s time for a look back even further, to that film’s true progenitor: the French TV program LES DOCUMENTS INTERDITS, or THE FORBIDDEN FILES. The brainchild of Jean-Teddy Filippe, an award-winning director of TV commercials, this series began in 1985 as LES RENDEZ-VOUS MANQUES, or THE MISSED APPOINTMENTS, which grew into the two-season LES DOCUMENTS INTERDITS. It consists of twelve short faux-documentaries broadcast in 1988-89—and a thirteenth in 2010—on France’s La Sept (later Arte) network. The program was a marked success (even if it is largely unknown on these shores), and its continuing relevance is evident in THE BLAIR WITCH PROJECT and the innumerable found footage films that followed in its wake.

Found footage is indeed the term for LES DOCUMENTS INTERDITS’ thirteen episodes, which range in length from 3 to 19 minutes. Nearly all of them revolve around subject matter at, in the words of its creator, “the border of the real, where the known and the unknown constantly intertwine” (making the show something of a forerunner of THE X-FILES and BLACK MIRROR in addition to BLAIR WITCH). All purport to be actual filmed documents created by people who are unwittingly made witness to various odd and inexplicable phenomena—and end up more often than not vanishing mysteriously.

To hear Filippe tell it, LES DOCUMENTS INTERDITS functions as a sophisticated commentary on the phoniness of televised “reality” and the over-readiness of viewers to  believe everything they see. If that was indeed the intent than these DOCUMENTS perhaps did their job a little too well, as innumerable people thought these mock-docs were real—a misconception bolstered by La Sept, which initially broadcast the series with no indication that it was staged. The deception was eventually revealed, with actor Jean-Claude Carrière appearing after the broadcast of the final episode to inform viewers of the program’s true nature. That, of course, didn’t stop people from continuing to believe in the veracity of what they saw; even today clips from this program are being passed off as “astonishing real” footage.

believe everything they see. If that was indeed the intent than these DOCUMENTS perhaps did their job a little too well, as innumerable people thought these mock-docs were real—a misconception bolstered by La Sept, which initially broadcast the series with no indication that it was staged. The deception was eventually revealed, with actor Jean-Claude Carrière appearing after the broadcast of the final episode to inform viewers of the program’s true nature. That, of course, didn’t stop people from continuing to believe in the veracity of what they saw; even today clips from this program are being passed off as “astonishing real” footage.

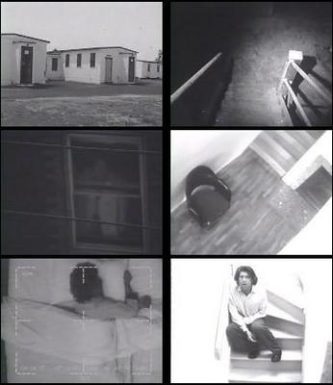

The series’ primary lure is its simplicity. Cinematically distinguished it isn’t, and that’s part of its charm; these scrappily lensed mini-films really look like the found documents—either amateur home video or surveillance camera footage—they’re supposed to be. Lasting from three to ten minutes in length, the documents are generally soundless, with dual narration tracks overlaid to explain what’s going on (we’re constantly assured that what we’re seeing is being presented “without editing, exactly as we found it” and frequently encouraged to “watch closely what’s about to happen”), one spoke by a woman in French and the other by a stern, deep voiced man in English.

This format also allows for a certain amount of teasing ambiguity that Filippe uses to his advantage. The program may be technically primitive but there’s a real ingenuity to it, as evinced by those duel narration tracks, which according to Filippe diverge from each other in subtle, and apparently significant, details. See also the many LES DOCUMENTS INTERDITS tribute videos (such as this one and this one) that have turned up on YouTube, which have none of the eeriness and transcendent charm of the Filippe directed original episodes.

The six episode first season of LES DOCUMENTS INTERDITS, filmed in black and white with highly primitive production values, began with “The Shipwreck.” It’s a 7 minute film made, purportedly, by the sole survivor of the sinking of a Soviet cargo ship, an unidentified man who finds himself marooned on a lifeboat. He vacillates wildly between despair and a curious euphoria, claiming to be in contact with some supernatural phenomenon, about which he leaves a half-effaced message on the lifeboat: “Those who have seen it can never come back, it’s the—” As for the man himself, he’s seen eventually abandoning the boat and swimming away.

This effectively sets the tone for the following episodes, which generally conclude with their protagonists disappearing into the unknown. That’s certainly true of “The Ghosts,” an 8 minute tale that was inspired, evidently, by the books of Carlos Castaneda. It takes the form of a filmed diary made by a young man in 1953, depicting himself and two companions trekking through a Mexican desert infested, it’s claimed, with all manner of spirits. Inevitably two members of the party end up mysteriously disappearing.

“The Divers” lasts 4 minutes. It’s set in “a part of the world we cannot situate,” where members of an unidentified commando unit attempt to rescue a mysterious man in the sea, only to find that this individual doesn’t exactly need rescuing—although the unit members definitely do!

“The Divers” lasts 4 minutes. It’s set in “a part of the world we cannot situate,” where members of an unidentified commando unit attempt to rescue a mysterious man in the sea, only to find that this individual doesn’t exactly need rescuing—although the unit members definitely do!

“The Pinic” [sic], lasting 5 minutes, concerns a young camera buff making a car journey with some hippie friends in America, circa 1970. After lengthy walks through sandy canyons one of the party mentions hearing music that sounds “like crystal bubbles,” and eventually runs off.

“The Witch” likewise lasts just 5 minutes, but is far more elaborate than its predecessors—and ultimately less affecting. Taking place in two distinct time periods, it spins a complex (overly so in my view) narrative that involves a disappearing house, a shape-shifting sorceress and a ravenous mob.

“The Soldier” runs 4 minutes and is set in 1943. It’s the filmed diary of an American soldier in Sicily who spots some mysterious figures who appear to walk on water. They ultimately lure the soldier into the sea, from which he never emerges.

“The Soldier” runs 4 minutes and is set in 1943. It’s the filmed diary of an American soldier in Sicily who spots some mysterious figures who appear to walk on water. They ultimately lure the soldier into the sea, from which he never emerges.

So ends season one. Season two, due to a more generous budget (part of it supplied by an American source), is more ambitious, utilizing color film stock and a “special thanks” at the end of each episode to the fictional organizations referenced therein. Also, UFOs were added to the ghosts and atmospheric phenomena depicted in season one.

More importantly, this second batch of documents evince a far more sophisticated construction, particularly in their juxtaposition of image and narration. Crucially, a number of important plot points are left unshown, with the narration filling them in for us—a device that works far better than you might expect given that the lure of the unknown is such an important part of the series—just as oftentimes the narrators’ descriptions differ quite markedly from what we see.

The season begins with “The Madman at the Crossroads,” lasting 8 minutes, about a US based Hungarian mechanic who claims to have been abducted by a UFO in 1954. Eventually we’re shown footage from the film the man made of his ordeal, which shows only the surface of the moon.

The 7 minute “The Child” appears to have been inspired by the classic TWILIGHT ZONE episode (and 1953 Jerome Bixby story) “It’s a Good Life.” It takes the form of a filmed diary made by a man devastated by his supernaturally endowed son, who can make things happen with his mind, including murder—which, in an example of Filippe’s careful delineation between the seen and unseen, is depicted entirely off-screen.

“The Extra-Terrestrial” lasts 6 minutes, and takes place at a military experimentation camp in 1969. The episode consists largely of surveillance camera footage of a man–actually an alien in human guise–detained in the camp, and expiring a day before Neil Armstrong sets foot on the moon.

“The Ferguson Case” is, at 13 minutes, the longest document yet (and the most BLAIR WITCH-like). It takes the form of a mock tabloid news broadcast whose motto is “We are on the lookout for anything, and we show everything!” Upon receiving a cryptic phone call from a woman claiming “they” are inside her house and moving around, a camera crew is sent to the house in question. They arrive to find a darkened, and seemingly empty, residence…

The last episode is the 9 minute “Siberia.” It concerns a government sponsored biomechanics program intended to turn humans into robots, and consists of an extended interview with a man with a robotic arm that has a tendency to act on its own, leaving him in some highly bizarre situations—as when the robotic hand becomes stuck to a window pane, and is pried away only after being blasted with a blowtorch and whacked with a hammer.

So concluded LES DOCUMENTS INTERDITS. Jean-Teddy Philippe went on to direct a great deal of episodic television and French TV movies, and even attempted (and discarded) a feature film, to be called LA FEMME PERDUE/THE LOST WOMAN, in the style of the documents. There was (and still is) much talk about a 13th Document Interdit that “seems to be missing.” That document finally saw the light of day in 2010, on the occasion of the Twentieth anniversary of Arte TV.

The twenty-years-after-the-fact “The Examination” runs 19 minutes, and is far different in tone, style and impact from its predecessors. It’s a veritable epic, alleging to have been culled from 22 years’ worth of surveillance camera footage left by a compulsive amateur videographer and scam artist. Missing is the supernatural bent of the earlier episodes, with the driving force being the more mundane, though just as horrifying, specter of human psychosis.

The setting is West Berlin, where the videographer scam artist decides to impersonate Peter, a man he closely resembles. The protagonist spies on Peter and his family via cunningly concealed surveillance cameras, eventually kidnapping Peter and stashing him, tied to a chair, in a secure location while taking his place and recording virtually the entire drama. This makes for a document that comes to encompass multiple murders and corpse defilement, visualized largely through windows, gratings, wire mesh, half-closed doors, etc., and with narration that has an appropriately halting, awkward lilt, enhancing the sense of realism and also the psychopathology of the protagonist (focusing as he does on getting the words right and not the emotional resonance of the acts described). It is, in short, an altogether dazzling piece of Mauvais genre, and the most impacting of all the DOCUMENTS INTERDITS, making one wish Filippe had continued the series.

The setting is West Berlin, where the videographer scam artist decides to impersonate Peter, a man he closely resembles. The protagonist spies on Peter and his family via cunningly concealed surveillance cameras, eventually kidnapping Peter and stashing him, tied to a chair, in a secure location while taking his place and recording virtually the entire drama. This makes for a document that comes to encompass multiple murders and corpse defilement, visualized largely through windows, gratings, wire mesh, half-closed doors, etc., and with narration that has an appropriately halting, awkward lilt, enhancing the sense of realism and also the psychopathology of the protagonist (focusing as he does on getting the words right and not the emotional resonance of the acts described). It is, in short, an altogether dazzling piece of Mauvais genre, and the most impacting of all the DOCUMENTS INTERDITS, making one wish Filippe had continued the series.