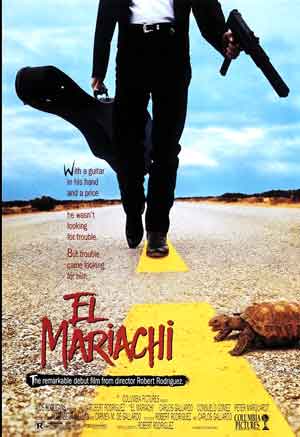

In the past decade there was one film above all others that inspired filmmakers in and out of the horror genre, and it isn’t even a horror movie. Its 1992’s EL MARIACHI, an ultra-low budget effort by filmmaker Robert Rodriguez. Rodriguez has of course gone on to make bigger and better films—FROM DUSK TILL DAWN, the SPY KIDS trilogy and SIN CITY—but I’m willing to bet he’s destined to be remembered for EL MARIACHI, the legendary Seven Thousand Dollar Movie.

EL MARIACHI (1992) Trailer

Today’s young filmmakers probably have no idea of what a bombshell EL MARIACHI was during the early-to-mid nineties. I was a film student at the time, and recall endless conversations about the film’s production, its ultra-low budget, and how it was grabbed up for distribution by Columbia Pictures, who furthermore gave its penniless creator a reported $5 million to make a sequel, 1995’s DESPERADO. It was the ultimate Hollywood fairy tale, and the media gobbled it up: quite simply, in 1992-93 it was damn near impossible not to come across an item in print or on TV about Robert Rodriguez and his $7,000 movie.

DESPERADO (1995) Trailer

The situation was this: Rodriguez, a 23-year-old kid living in Texas, decided to make a trilogy of cheap action-exploitation movies and sell ‘em to the Mexican video market. He raised seven thousand dollars during a month-long stay at a medical research facility and used that money to shoot EL MARIACHI over the course of a few days in a Mexican border town. Once he was finished editing the film his plans went awry, albeit in a good way: a Hollywood agent saw EL MARIACHI and was so impressed he showed it around, instituting a feeding frenzy among the major studios and resulting in Rodriguez having his $7,000 movie given wide theatrical distribution, and becoming a bonafide Hollywood player in the process.

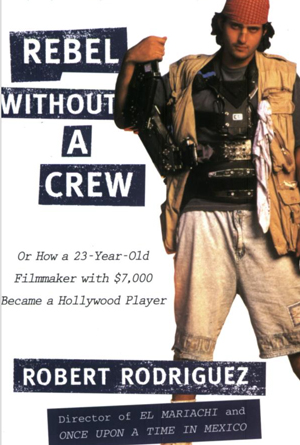

That was the story we were fed by an extremely accommodating media, but not quite the reality. On the film nerd circuit in which I ran word quickly got out that the film we viewed in theaters was not the one Rodriguez shot for $7,000, and that Columbia shelled out upwards of $100,000 to “clean it up”, money the studio apparently “never made back”. Resentment set in quickly among those of us who realized it was impossible to properly lens and process a feature film for $7 grand. Typical were the following comments from filmmaker P.J. Pesce: “If Robert Rodriguez made that film for $7,000, he didn’t feed his crew.” (Actually, he didn’t have a crew.) Continuing with Mr. Pesce: “Someone should do the math and figure out if you can even process that much film stock for that money.” (Apparently Rodriguez never processed any film stock, just a quarter inch video tape from which the studio made the celluloid print.) “I mean, what did the guy do? He made a Renny Harlin movie. A Hollywood movie. A calling card. He’s not opening things up, he’s closing them down.” (Incidentally, P.J. Pesce went on to direct FROM DUSK TILL DAWN 3, which Rodriguez executive produced–small world, eh?) It’s a good thing Rodriguez released a book in 1995 that set the record straight on the making of EL MARIACHI, as he was in serious danger of getting stoned to death by disillusioned film geeks.

The book in question was REBEL WITHOUT A CREW, which I and damn near all my friends rushed—and I do mean RUSHED—out to buy within days of its appearance on bookstore shelves. It consists of Rodriguez’s diary entries written prior to, during and after the shooting of EL MARIACHI; the premiere installment of his “Ten Minute Film School” (a feature he’s continued on the DVDs of all his subsequent films); and his near-incomprehensible shooting script for MARIACHI, which he deserves credit for including in unadorned warts-and-all form. REBEL WITHOUT A CREW is a good book, honest and straightforward about MARIACHI and its meteoric success…although readers can be forgiven for seething with jealousy over Rodriguez’s claims of being enthusiastically courted by a big time Hollyweird agent after the latter caught a glimpse of a “great shot” on the tiny screen of a movieola upon which Rodriguez was editing; getting flown back and forth between Texas and LA and put up in ritzy hotels by movie studios all desperate to nab Rodriguez, the Next Big Thing; and generally getting his ass kissed by the likes of David letterman, Barbet Schroeder, Quentin Tarantino, Alfonso Arau, Harold Becker and Mark Canton. It’s truly the stuff fairy tales are made of, a once-in-a-lifetime account I’m certain could NEVER happen today.

But then, Rodriguez’s success was not all that common back then, either! Readers of REBEL WITHOUT A CREW are strongly advised to crack THE UNKINDEST CUT by Joe Queenan, published earlier the same year. It’s about the author’s bungled attempts at making his own $7,000 feature in direct imitation of Rodriguez’s achievement. The flipside of REBEL WITHOUT A CREW, THE UNKINDEST CUT is a scathingly funny account of how Queenan, a thirtyish free-lance columnist, nearly bankrupted his family and alienated most of his friends during production of an opus called SEVEN STEPS TO DEATH, which was ultimately never distributed and ended up costing its creator a not-inconsiderable $65 grand.

In my experience the above is depressingly representative of the reality confronted by those who tried to make their own $7,000 films in EL MARIACHI’S wake. I should know, as I and several fellow film students made our own no-budget feature in 1995, a four-parter called THE LAYPERSON’S GUIDE TO MODERN LIVING. It was by no means inspired by MARIACHI, although you can be sure Rodriguez’s epic was never far from our thoughts (I recall a lengthy phone conversation with the film’s producer about the various things Rodriguez accomplished with MARIACHI and how those things paralleled or didn’t parallel our own moviemaking experience.) Not that this helped LAY PERSON’S chances on the marketplace, as our film ended up costing close to what SEVEN STEPS TO DEATH did, and, like that opus, failed to secure distribution anywhere. Makes me wonder how many other unreleased no-budget features exist, fueled by the impossibly high hopes fostered by EL MARIACHI.

The great irony here is the simple fact that EL MARIACHI was never all that good a movie. The jumbled account of a guitar player who’s mistaken for a bounty hunter in a small Mexican town, it’s certainly energetic, with ultra-kinetic handheld camerawork, and contains a number of impressive action sequences that belie its micro-budget. But the film is a washout dramatically, with a repetitive storyline that grows old very quickly and an overabundance of tired action movie clichés. It seems downright bizarre the way independent filmmakers embraced EL MARIACHI, as it would seem to represent everything the indie movement is against: it’s shallow, violent, derivative and all-too-eager to forsake things like story and character in favor of mindless action. In short, it’s very Hollywood, which explains why the big studios were so taken with it.

It also explains, I’m guessing, why most of the seminal texts on independent filmmaking in the nineties—in particular SPIKE, MIKE, SLACKERS AND DYKES by John Pierson and DOWN ‘N DIRTY PICTURES by Peter Biskind—did their best to downplay Robert Rodriguez and EL MARIACHI (Biskind: “Rodriguez, who had a great eye, was, as his future films would confirm, in all other aspects a delayed adolescent”). But the film’s impact is undeniable: read Billy Frolick’s WHAT I REALLY WANT TO DO IS DIRECT (1996), about seven film school graduates attempting to find work in Hollywood during the mid nineties. Several of the participants reference EL MARIACHI in much the same way I and my buddies did back in the day. Frolick’s book is the source for the above P.J. Pesce quotes, which, you’ll recall, were far from effusive. No, not everyone was complimentary to it, but EL MARIACHI, it seems, was on everyone’s mind.

Certainly there have been other attention-getting no-budget features that came before (BLOOD SIMPLE, SEX LIES AND VIDEOTAPE, RESERVOIR DOGS) and after (THE BROTHERS McMULLEN, THE BLAIR WITCH PROJECT, CABIN FEVER) the bow of EL MARIACHI, many of which have been more successful at the box office (correction: they all were), but none, I’d argue, have had the same impression. If ever a film caught the zeitgeist of its time, EL MARIACHI was it. Furthermore, it retains much of its allure today: the film remains readily available on DVD and is still an occasional topic of conversation in my crowd, long after other trendy indies of the time have been forgotten. Anyone remember AMONGST FRIENDS? COMBINATION PLATTER? BOXING HELENA? In such company EL MARIACHI did and does stand out. Indeed, I’d even go so far as to dub my generation of filmmakers The Spawn of EL MARIACHI.

Okay, so we’ve established EL MARIACHI retains an allure that’s unprecedented, but one crucial question remains unanswered: why is this film such an attention getter? What precisely makes it resonate fourteen years after its inception? I haven’t seen it appear on too many favorite movie lists, with most people I know admitting it’s a so-so film at best. In addition, much of the hype that surrounded its inception back in the early nineties has been revealed as horseshit. So what’s the answer?

It has more to do, I think, with EL MARIACHI’S reception rather than its quality (or lack thereof), with the fairy tale aspect of a nobody who made a no-budget movie and became a Hollyweird mainstay overnight. (Fairy Tale is a term I’ve used several times in this essay, and with good reason.) This is certainly not the only instance of such, but it’s likely the most elemental example of the fulfillment of a dream as old as Hollywood itself, and one I strongly doubt will ever go out of style. In the words of THE UNKINDEST CUT author Joe Queenan, “Deep down inside, everybody in the United States has a desperate need to believe that some day, if the breaks fall their way, they can quit their jobs as claims adjusters, legal secretaries, certified public accountants, or mobsters, and go out and make their own low-budget movie. Otherwise, the future is just too bleak.”

So go ahead: watch EL MARIACHI, read REBEL WITHOUT A CREW and follow Robert Rodriguez’s lead. Make your own $7,000 movie—I and seemingly everyone else from my generation have already tried it. But please, when it’s all over don’t say I didn’t warn you!