Brazil’s Walter Hugo Khouri (1929-2003) was an unknown master of horror filmmaking. Granted, only two of his 20-plus films were horror themed, but THE ANGEL OF THE NIGHT and DAUGHTERS OF FIRE are unquestioned genre standouts, marked by finely crafted suspense, atmospheric visual design and David Lynch-worthy surrealism.

Brazil’s Walter Hugo Khouri (1929-2003) was an unknown master of horror filmmaking. Granted, only two of his 20-plus films were horror themed, but THE ANGEL OF THE NIGHT and DAUGHTERS OF FIRE are unquestioned genre standouts, marked by finely crafted suspense, atmospheric visual design and David Lynch-worthy surrealism.

Khouri, one of Brazil’s most prolific and respected filmmakers, forged a nearly five decade career that both preceded and outlasted the Cinema Novo movement of the 1960s and 70s. Khouri’s early films, which included 1958’s ESTRANHO ENCONTRO and 1959’s LONESOME WOMEN/FRONTEIRAS DO INFERNO, were highly existential and contemplative in nature. His masterpiece is alleged to be 1964’s Antonioni inspired MEN AND WOMEN/NOITE VAZIA, which is as potent a cinematic portrayal of urban disconnection and alienation as any you’ll see. However, I (having seen quite a few Khouri films) feel Khouri’s finest work was in his two 1970s-era excursions in horror.

1972’s Bergmanesque THE GODDESSES/AS DEUSAS contains hints of horror in its visually rapturous depiction of two women going sexually and psychologically bonkers in a scenic yet profoundly eerie rural environ. THE GODDESSES also explicitly prefigures THE ANGEL OF THE NIGHT and DAUGHTERS OF FIRE in its female-centered evocation of the corrosive effects of a seemingly idyllic landscape; indeed, the three films nearly form a trilogy.

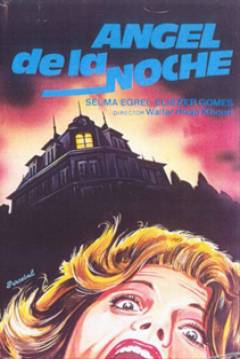

The first of Khouri’s true horror films, the multi-award winning THE ANGEL OF THE NIGHT/O ANJO DA NOITE, appeared in 1974, and so prefigured HALLOWEEN and WHEN A STRANGER CALLS in its depiction of a young woman receiving threatening phone calls while looking after two children in a secluded mansion. Yet the proceedings are also very much in keeping with the tortured existentialism of Khouri’s previous films.

As an exercise in chilly minimalism the film is effective, even though it contains a lot of evident padding. That’s particularly true in the excessively drawn-out opening ten minutes, in which the heroine takes a never-ending bus ride to the mansion where most of the film takes place. But O ANJO DA NOITE is otherwise quite strong, with an expertly delineated atmosphere of creeping apprehension.

As he demonstrated in his non-horror films, Khouri had a visual eye that was second to none, and makes especially good use of the empty spaces and creepy statues of the mansion’s interior. Equally well utilized is the scenic countryside locale, which is made to seem ominous and menacing through lengthy tracking shots that suggest a malevolent P.O.V. (several years before HALLOWEEN popularized such an approach).

The lead actress Selma Egrei is quite strong, commanding an enormous amount of sympathy while simultaneously keeping us on edge about her true nature. Khouri’s filmmaking is instrumental in this aspect by never letting us hear the unseen phone caller, making us wonder if Ana’s claims about what is said are entirely honest. I won’t reveal the outcome, but will caution that the denouement is profoundly grim—this is, after all, a Walter Hugo Khouri film.

One more thing: for some reason, as of 2016 it seems the only available prints of O ANJO DA NOITE are in black-and-white—and severely faded and scratched up black-and-white—even though it was filmed and exhibited in color.

Daughters of Fire (Full Movie)

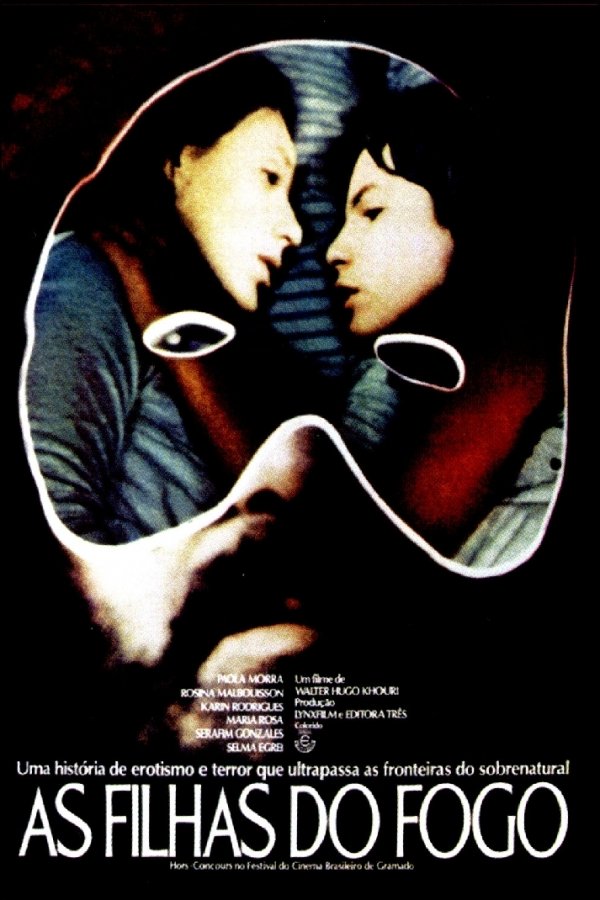

It took four years (during which Khouri directed another three films) for Khouri’s next excursion in horror to arrive, but 1978’s DAUGHTERS OF FIRE/AS FILHAS DO FOGO was worth the wait. Highly refined and atmospheric in nature, it makes for an excellent fit with more celebrated soft-spoken genre fests like CARNIVAL OF SOULS and DON’T LOOK NOW.

It’s about the inquisitive young Ana (Rosina Malbouisson), who goes to stay with her friend Diana (Paola Morra) at the latter’s country home, where the two waste no time initiating a lesbian relationship. Also residing in the area are a mysterious vagrant and an old woman who claims she can speak with the dead. The protagonists gradually fall under the old woman’s malevolent spell amid a succession of horrific events, which include an unexplained killing, periodic appearances by Diana’s long-dead mother and an odd Pagan-esque ritual performed by the vagrant. Then there’s the creeping vegetation invading Diana’s home, which grows downright horrific and threatening before long.

A fascinating and confounding film to be sure, although it’s annoyingly reactionary in its portrayal of lesbianism (with the unmistakable implication that the protagonists’ “forbidden” relationship is a key component in their bleak fate). Yet there are definite flashes of brilliance on the part of Khouri, who as in THE ANGEL OF THE NIGHT makes excellent use of the deceptively placid Brazilian countryside. He also succeeds in creating a deeply ominous atmosphere of encroaching darkness, with pointed visual motifs (zoom-ins on household plants, etc.) that subtly foreshadow the surreal denouement.

The eroticism of DAUGHTERS OF FIRE and many of Khouri’s other seventies-era films appears to have heavily informed his subsequent filmography, which is quite sexual in nature (and has led to him being labelled a “soft porn auteur”). The most memorable of those later films is probably LOVE STRANGE LOVE/AMOR ESTRANHO AMOR from 1982, which achieved notoriety due to the fact that one of its co-stars, future Brazilian kid show host Xuxa Meneghel, plays a frequently nude prostitute. The film overall, however, is a far cry from Khouri’s best work, as are other late Khouri efforts like EROS, O DEUS DO AMOR and AMOR VORAZ.

It’s a shame Walter Hugo Khouri only made two horror films in his lifetime, as he clearly had an affinity for the genre. In this respect he joins world-renowned auteurs like Ingmar Bergman (who made an interesting excursion into horror territory in THE HOUR OF THE WOLF), Federico Fellini (who went effectively horrific in the unforgettable “Toby Dammit” segment of SPIRITS OF THE DEAD), Werner Herzog (whose remake of NOSFERATU is a genre classic), and Robert Altman (whose IMAGES and THREE WOMEN both liberally partook of horror movie iconography), who all proved quite adept at crafting scary cinema, proving that the line between horror and arthouse filmmaking is a thin one indeed.