The late Juraj Herz was the Czech Republic’s cinematic master of all things fantastic. His filmography, which commenced in the 1960s, encompassed every conceivable genre, but it’s the eleven horrific and fantastic films profiled below for which Herz is best known. Those films are admittedly frustratingly uneven, often due to governmental interference (a problem that has dogged Herz throughout his career), but his achievement in the realm of fantastic cinema is assured.

The late Juraj Herz was the Czech Republic’s cinematic master of all things fantastic. His filmography, which commenced in the 1960s, encompassed every conceivable genre, but it’s the eleven horrific and fantastic films profiled below for which Herz is best known. Those films are admittedly frustratingly uneven, often due to governmental interference (a problem that has dogged Herz throughout his career), but his achievement in the realm of fantastic cinema is assured.

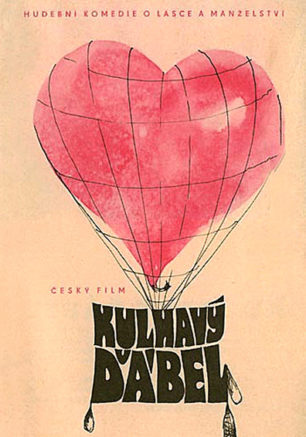

Juraj Herz’s interest in the fantastic was first evinced in KULHAVY D’ABEL (THE LIMPING DEVIL), which appeared in 1968. Very much a product of its time, it’s a heavily stylized, psychedelic account that introduced the superbly textured visuals and elaborate set design that would come to define his films. Unfortunately, it  bore another attribute common to his later work: censorship, which was apparently responsible for, in Herz’s own words, “depluming” the film.

bore another attribute common to his later work: censorship, which was apparently responsible for, in Herz’s own words, “depluming” the film.

Bold and anarchic in its approach, KULHAVY D’ABEL features copious musical numbers, visuals that haphazardly shift from black-and-white to bold primary color, occasional animated segues and a tone that wavers between comedic and horrific. Herz himself, with his Peter Sellers-esque looks, plays Asmodeus, a mythological demon who amuses himself by creating random couplings amid his human subjects. When his latest attempt at creating a relationship is thwarted by the intervention of a love-struck young man named Honza (Vaclav Neckar), Asmodeus becomes determined to thwart him, inducing a lengthy dream journey in which Asmodeus shows Honza the many unpleasant facets of love—not that it does any good! The film is a trifle, certainly, but a striking one.

THE CREMATOR (SPALOVAC MRTVOL), which also debuted in 1968, is a far more resonant work. Set in the 1930s, it’s told from the cockeyed viewpoint of Mr. Kopfkringl, a cremator. An almost impossibly cheerful man, Kopfkringl loves his job, which he sees as returning people’s bodies to where they originated. Unfortunately Kopfkringl finds his happy-go-lucky state waning as poisonous Nazi ideals increasingly contaminate his thinking. This is especially problematic considering that his wife has Jewish blood in her veins, which inspires Kopfkringl to take some drastic actions (hint: they involve his occupation).

THE CREMATOR (SPALOVAC MRTVOL), which also debuted in 1968, is a far more resonant work. Set in the 1930s, it’s told from the cockeyed viewpoint of Mr. Kopfkringl, a cremator. An almost impossibly cheerful man, Kopfkringl loves his job, which he sees as returning people’s bodies to where they originated. Unfortunately Kopfkringl finds his happy-go-lucky state waning as poisonous Nazi ideals increasingly contaminate his thinking. This is especially problematic considering that his wife has Jewish blood in her veins, which inspires Kopfkringl to take some drastic actions (hint: they involve his occupation).

Loosely adapted from a novel by Ladislav Fuks, the film is marked by a (deliberately) meandering non-story. Herz favors handheld camerawork and ultra-wide angle lenses, which lend a real sense of tension and unease to even the most mundane sequences. The set-ups are wildly baroque and expressionistic, especially toward the end, when the protagonist appears framed before a reproduction of Bosch’s “The Garden of Earthly Delights” (Herz, for the record, has since claimed that he finds the film’s stylistic choices overwrought).

In such a visually concentrated work it’s inevitable, I guess, that the performances take a back seat. Rudolf Hrusinsky as Kopfkringl goes clear over the top, and Herz does little to rein him in. The character may function as an exaggerated caricature, but I say Hrusinsky overdoes it: his Kopfkringl is such a weirdie it hardly seems a stretch when he goes mad. But as a purely visual exercise THE CREMATOR is quite an achievement, with the overall effect being one of macabre fascination and profound disquiet.

1971’s MORGIANA, with its baroque visuals and deliriously melodramatic storyline, is often cited as the final entry in the Czech cinematic New Wave of the  1960s (which included films like DAISIES, THE FIREMEN’S BALL and of course THE CREMATOR), even though Herz never formally identified himself with the movement. The film was quite controversial in its native land, so much so that Herz claims he was forbidden to make any features for two years following its completion.

1960s (which included films like DAISIES, THE FIREMEN’S BALL and of course THE CREMATOR), even though Herz never formally identified himself with the movement. The film was quite controversial in its native land, so much so that Herz claims he was forbidden to make any features for two years following its completion.

MORGIANA, based on a short story by Alexandr Grin, was conceived quite differently than it turned out. The conceit of actress Iva Janzurova playing dual roles was apparently due to the fact that her characters were originally intended as different facets of a single person, but government regulators took issue with that interpretation and forced Herz to make a film he admittedly “didn’t like.”

It takes place in an unidentified 19th Century setting of decadent opulence, where the vivacious blonde Klara and the pouty brunette Viktoria live a charmed existence. Viktoria, however, grows increasingly jealous of her sister and poisons her, but the poison somehow manages to spread to much of the surrounding population. The poisoned Klara, meanwhile, finds herself drifting into an increasingly hallucinatory reality and eventually expires…or at least seems to.

The proceedings are marked by delirious visuals conjured by Herz and cinematographer Jaroslav Kucera. The color scheme is a gaudy one and the ever-fluid camerawork extremely expansive. Credit must also be given to Iva Janzurova’s duel performances and Lubos Fiser’s noisy and insistent yet resonant music score (which was recently released on CD by Finders Keepers), which aids immeasurably in creating an atmosphere of melodramatic delirium. The tacked-on happy ending, however, could definitely have used some work.

Herz’s VIRGIN AND THE MONSTER (PANNA A NETVOR), from 1978, is perhaps the darkest-ever cinematic interpretation of the “Beauty and the Beast” fairy tale.

Herz’s VIRGIN AND THE MONSTER (PANNA A NETVOR), from 1978, is perhaps the darkest-ever cinematic interpretation of the “Beauty and the Beast” fairy tale.

The Beauty here is Julie (Zdena Studenkova), the daughter of a bankrupt merchant who’s been sentenced to death for plucking a rose in the “Haunted Woods.” In an effort to save her father’s life Julie travels to the Haunted Woods and the gloomy castle situated therein. There resides Netvor (Vlastimil Harapes), a fearsome creature who shuns the human world but has eyes for Julie. Netvor uses magic to keep Julie in his employ, all the while hiding his face, but eventually she spots his visage in a mirror and freaks out—yet is unable to fully shake his hold on her.

Herz follows the perimeters of the original fairy tale reasonably closely, but what makes this THE VIRGIN AND THE MONSTER distinct is its incredibly vivid atmosphere of grit and despair. Technically the film is a veritable gothic wet dream, from the dark-hued photography to the haunting organ score to the artfully decayed, cobwebby production design. With all the darkness it’s no surprise that the romance so integral to the tale barely registers, and that the happy ending falls woefully flat. Nor, for that matter, is there much of a narrative of any sort, as Herz is concerned primarily with atmosphere and visual splendor—and in those areas, at least, he and his collaborators have definitely succeeded.

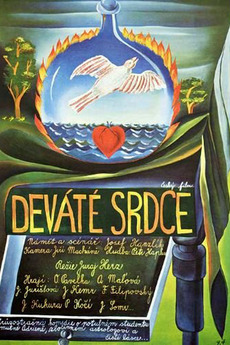

Herz’s next excursion in the fantastic was THE NINTH HEART (DEVATE SRDCE) from 1979, and it was a definite  step down. In fact, the film’s first half is plain bad, suffused with a cloyingly cutesy aura. It concerns a vagrant student (Ondrej Pavelka) residing in an enchanted land who’s given an invisibility cloak that allows him to wriggle out of quite a few tense situations, at least until he’s enlisted in a quest to free a captive princess (Julie Juristova). She’s imprisoned in a castle by a scumbag magician (Juraj Kukura) who’s looking to prolong his life by imbibing blood from the hearts of children—nine of them, to be exact.

step down. In fact, the film’s first half is plain bad, suffused with a cloyingly cutesy aura. It concerns a vagrant student (Ondrej Pavelka) residing in an enchanted land who’s given an invisibility cloak that allows him to wriggle out of quite a few tense situations, at least until he’s enlisted in a quest to free a captive princess (Julie Juristova). She’s imprisoned in a castle by a scumbag magician (Juraj Kukura) who’s looking to prolong his life by imbibing blood from the hearts of children—nine of them, to be exact.

It’s at this point that the film picks up, with the tone growing quite dark and evocative. The same is true of the visual design, whose wonders include a splendorous candlelit room where time runs on a different course than it does in the rest of the world, and so causes the people in it to grow old at an extremely advanced rate. The special effects, I should mention, were accomplished by the great Jan Svankmajor, but are surprisingly unimpressive, consisting of rudimentary stop motion (such as a line drawn in chalk by the invisible protagonist) and puppet work that fails to make the most of Svankmajor’s—and Herz’s—staggering abilities.

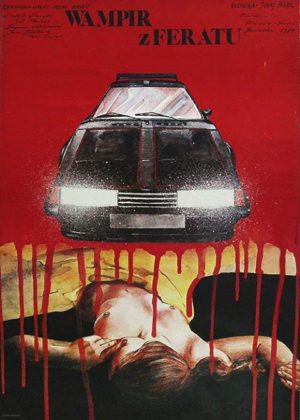

1981’s FERAT VAMPIRE (UPIR Z FERATU) added a strain of satiric comedy to Herz’s unique brand of dark fantasy, as is evident in the film’s premise: a vampire car called a Ferat (as Nos_ _ _ _ _u) that drains its driver’s life essence.

1981’s FERAT VAMPIRE (UPIR Z FERATU) added a strain of satiric comedy to Herz’s unique brand of dark fantasy, as is evident in the film’s premise: a vampire car called a Ferat (as Nos_ _ _ _ _u) that drains its driver’s life essence.

According to Herz himself, who has publicly branded this film a “disaster,” government censors crippled FERAT VAMPIRE at the screenplay stage. That would explain the sparseness of the narrative, although the shockingly unexpressive filmmaking is a bit harder to forgive. Considering that the titular automobile is a souped-up hot rod, one might reasonably expect a lot of high speed action—and certainly the exciting opening, in which the Ferat is pursued by renegade ambulance drivers, seems to promise that—which makes it all the more dispiriting that the whole thing is so talky and unexciting. The climax is good, I’ll say that, with the heroine (Dagmar Havlova) taking the Ferat for a final drive and getting her energy drained in the process, but by then it’s strictly a case of far too little, way too late.

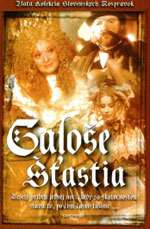

GALOSE STASTIA (THE OVERSHOES OF HAPPINESS; 1986) is a sporadically effective fantasy based on a Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale about a trio of seductive fairies (Jana Brejchova in a duel role and Tereza  Pokorna) who procure a pair of magical galoshes that promise to fulfill their human wearer’s most coveted desire. It would seem the shoes are the key to happiness, but as it turns out that’s not the case, as one wearer ends up imprisoned in a hanging cage and another transformed into a galoshes-wearing parrot. Things are further complicated when one of the fairies falls in love with a human subject, much to the consternation of her fellows.

Pokorna) who procure a pair of magical galoshes that promise to fulfill their human wearer’s most coveted desire. It would seem the shoes are the key to happiness, but as it turns out that’s not the case, as one wearer ends up imprisoned in a hanging cage and another transformed into a galoshes-wearing parrot. Things are further complicated when one of the fairies falls in love with a human subject, much to the consternation of her fellows.

The film is plagued by problems that would come to mar quite a few of Herz’s late-period fantasies, including a cluttered narrative, uneven performances and so-so special effects. It looks good, at least, although in keeping with many other 1980s fantasy films the  visuals are distractingly hazy and smoke-filled.

visuals are distractingly hazy and smoke-filled.

I’d like to report that Herz’s films picked up from there, but I’m afraid that’s just not the case. For corroboration see THE FROG PRINCE (ZABI KRAL; 1990), a fleshing out of the famous Brothers Grimm fairy tale about a strapping young prince (Michal Dlouhy) cursed to live life as a talking frog until being kissed by his true love.

The film is visually impressive, with the gorgeous widescreen photography and lush scenery we’ve come to expect from Herz. The problem is with the by-the-numbers narrative, which does nothing particularly interesting with the tale, and the special effects—specifically the frog the prince turns into, a transformation Herz holds off until nearly an hour into the film. A wise choice, as the prince-frog is a thoroughly goofy-looking creation that I never found the slightest bit convincing, and leaves us with a film that works best as camp.

THE EMPEROR’S NEW CLOTHES (CISAROVY NOVE SATY; 1994) is even less inspiring. It’s notable, at least, for its sumptuous visual design depicting a  fantasy kingdom packed with what look like thousands of extras. Its basis is the popular fairy tale by Hans Christian Anderson about a vain emperor (Harald Juhnke) who demands a new set of clothes to wear each day, only to be tricked by a prankster (Jan Kalous) who offers to make magical clothes that only certain people will be able to see—or so he claims.

fantasy kingdom packed with what look like thousands of extras. Its basis is the popular fairy tale by Hans Christian Anderson about a vain emperor (Harald Juhnke) who demands a new set of clothes to wear each day, only to be tricked by a prankster (Jan Kalous) who offers to make magical clothes that only certain people will be able to see—or so he claims.

The problem is that the film was aimed at children, which explains the atmosphere of forced whimsy and the overdone happy ending. It’s a fact that Herz is at his best with dark and aberrant material, which this terminally lightweight film most definitely isn’t.

Herz’s quality depletion continued with 1996’s PASSAGE (PASAZ), a disappointing exercise in surreal apprehension.

Herz’s quality depletion continued with 1996’s PASSAGE (PASAZ), a disappointing exercise in surreal apprehension.

In this film a harried businessman (Jacek Borkowski) witnesses a person run down on a busy street outside an underground shopping mall. Borkowski responds by impulsively fleeing into said mall, where he undergoes all sorts of bizarre shenanigans, most of which tend to involve a mysterious film crew, an alluring prostitute and a strange little girl. It certainly sounds promising, but the visuals are shockingly pedestrian overall (despite some strikingly off-kilter camerawork), and the narrative pivots on a reality-warping “twist” that isn’t difficult to foresee. One can only imagine how PASSAGE might have played in the hands of David Lynch, or for that matter a young Juraj Herz.

The final film of this overview, and the last horror/fantasy film by Juraj Herz, is 2009’s DARKNESS (T.M.A.). Once again, it is not among his best work!

It involves a graphic artist (Ivan Franek) who moves back into the creepy house in which grew up. As you might guess,  he’s assailed with all manner of weirdness, including pipes that rattle so much they shake the entire house, chanting by spectral children and a break-in by an unseen someone—or something. Throughout it all he finds himself flashing back to his childhood, haunted by a mysterious sibling with whom he performed a barely-remembered horrific act.

he’s assailed with all manner of weirdness, including pipes that rattle so much they shake the entire house, chanting by spectral children and a break-in by an unseen someone—or something. Throughout it all he finds himself flashing back to his childhood, haunted by a mysterious sibling with whom he performed a barely-remembered horrific act.

This was perhaps the most overtly commercial film of Juraj Herz’s career. The artistry of his earlier films is absent, replaced with lurid gore, overdone Steadicam visuals and lightning-fast pacing. Yet DARKNESS proved that Herz, well into his seventies when it was made, hadn’t lost his filmmaking skill, and may well have had more interesting films in him. Sadly, we’ll never get to see them.

Juraj Herz: 1934-2018