Richard Stanley is one of the most interesting genre filmmakers on the scene, and also one of the least prolific. The South African bred Stanley burst upon the scene during (roughly) the same period as revered auteurs like Peter Jackson, Quentin Tarantino and the Coen brothers, although Stanley’s fortunes were more in line with those of Buddy Giovinazzo (of COMBAT SHOCK) and Jim VanBebber (DEADBEAT AT DAWN), i.e. filmmakers who are arguably just as gifted as their more famous contemporaries but whose careers panned out far differently.

Richard Stanley is one of the most interesting genre filmmakers on the scene, and also one of the least prolific. The South African bred Stanley burst upon the scene during (roughly) the same period as revered auteurs like Peter Jackson, Quentin Tarantino and the Coen brothers, although Stanley’s fortunes were more in line with those of Buddy Giovinazzo (of COMBAT SHOCK) and Jim VanBebber (DEADBEAT AT DAWN), i.e. filmmakers who are arguably just as gifted as their more famous contemporaries but whose careers panned out far differently.

Stanley began his career at age 24, with 1990’s HARDWARE. Released by Miramax (who Stanley has accused of “taking foreign movies and then marketing them to the lowest common denominator”), it was a financial success and a suitably intense and enjoyable film, even if it isn’t “the best science fiction thriller since ALIEN” (as an overenthusiastic Fangoria reviewer claimed). What it is is a good barometer of Stanley’s strengths and weaknesses; in the former category is an audacious mixture of subtlety  and intensity, with a cerebral art film sensibility coexisting quite harmoniously with extreme gore and violence, while in the latter category is the obnoxiously derivative nature of the script and visual design. All those things would characterize Stanley’s later films.

and intensity, with a cerebral art film sensibility coexisting quite harmoniously with extreme gore and violence, while in the latter category is the obnoxiously derivative nature of the script and visual design. All those things would characterize Stanley’s later films.

HARDWARE was adapted from a 1985 short entitled INCIDENTS IN AN EXPANDING UNIVERSE (which I’ll get to in a bit), and also took uncredited inspiration from a 1980 2000 A.D. comic called “SHOK!” The film is set in a pollution-choked futuristic landscape where a big city punk (Dylan McDermott) and his sculptor girlfriend (Stacey Travis) are menaced by scattered android scraps she plans to use in a sculpture, but which reconstitute themselves into what they started out as: a robotic population control device whose function is to destroy whatever gets in its way.

One might rightly complain that HARDWARE’S first hour is too arty for its own good, and the final third too implausible in its relentless cavalcade of destruction. The film also shows its influences—ALIEN, THE TERMINATOR (whose skinless form the android antagonist too-closely resembles) and THE TEXAS CHAINSAW MASSACRE—a bit too blatantly, while the performances of Stacey Travis and Dylan McDermott contribute very little to the proceedings outside the sight of Travis’ generously exposed body (it’s actually the late William Hootkins, in a small role, who makes the biggest impression acting-wise). But the film works, boasting gorgeously multi-hued visuals and a fully realized futuristic landscape.

Richard Stanley more than made good on the promise of HARDWARE with DUST DEVIL, a veritable epic of gore and magic set in the deserts of Namibia, Africa. It has its flaws (unavoidable considering the film’s troubled production history) but registers as a work of unique integrity and audacity.

The film was financed by England’s Palace Productions, who on the basis of HARDWARE’s success agreed to mount the far more ambitious DUST DEVIL. The calamitous shoot (as recoded in Stanley’s on-set diaries, published in the British anthology PROJECTIONS 3) was something of a nightmare, and postproduction an even bigger ordeal. Palace Productions went bankrupt during the process, leaving the film unfinished. The co-financier Miramax created an 87-minute cut, which was released on video in the US in 1993. Thankfully Stanley, using his own money, managed to buy back the negative and create a 103-minute director’s cut in 1994, followed by a 108 minute “Final Cut” that appeared on DVD in 2006.

The film was financed by England’s Palace Productions, who on the basis of HARDWARE’s success agreed to mount the far more ambitious DUST DEVIL. The calamitous shoot (as recoded in Stanley’s on-set diaries, published in the British anthology PROJECTIONS 3) was something of a nightmare, and postproduction an even bigger ordeal. Palace Productions went bankrupt during the process, leaving the film unfinished. The co-financier Miramax created an 87-minute cut, which was released on video in the US in 1993. Thankfully Stanley, using his own money, managed to buy back the negative and create a 103-minute director’s cut in 1994, followed by a 108 minute “Final Cut” that appeared on DVD in 2006.

Playing like a Spaghetti western (an influence that Stanley has admitted was quite intentional) crossed with an eighties slasher pic, the film is set in a vast South African desert. There a shape-shifting hitchhiker (Robert John Burke) is on a sex and murder spree. His path intersects with those of a headstrong white woman (Chelsea Field) and a black police inspector (Zakes Mokae), all of whom end up in an eerie ghost town half buried in sand.

DUST DEVIL surpasses HARDWARE in every respect. It’s impressively rendered in bold Sergio Leone-inspired visual compositions, and has excellent music by Simon Boswell that incorporates animal sounds and African chants (if it ultimately sounds a bit like the score for Alejandro Jodorowsky’s SANTA SANGRE that shouldn’t surprise, as Boswell also composed that film). The film’s windswept African locations make for a peerlessly haunting setting redolent of myth and prophecy; Stanley grew up in South Africa and shows a real feel for its deserts and waste lands.

But Stanley’s grand ambitions don’t always serve him well. The special effects are strictly of the B-movie variety, and fail to gel with the whole of the film, which despite its modest budget is A-list material all the way. Robert John Burke is strong in the (admittedly undemanding) lead part, while Chelsea Field is competent but not up to the demands of her complex role (she was forced on Stanley by the production company, having just appeared in THE LAST BOYSCOUT). Thus DUST DEVIL isn’t quite the masterpiece it aspired to be, but is still a vital work that demands to be seen more than once.

The ensuing 26 years were fallow ones for Richard Stanley, dominated by a handful of short films and documentaries, and the failure of what was intended to be Stanley’s magnum opus: THE ISLAND OF DR. MOREAU. That film’s epic unraveling was covered in the 2014 documentary LOST SOUL: THE DOOMED JOURNEY OF RICHARD STANLEY’S ISLAND OF DR. MOREAU, directed by David Gregory (who produced THE THEATER BIZARRE, which I’ll discuss below). In it we learn how Stanley, working with the biggest budget he’d ever been given, was forced out of the director’s chair after a few days, only to get rehired as a costumed extra, in which guise he was afforded an up-close view of the horrific mess the production became under the direction of the late John Frankenheimer. That mess is fully evident in the finished product, which was excreted to theaters in 1996.

Stanley was so shattered by the DR. MOREAU fiasco that he was hesitant about taking on a new feature (he reportedly turned down offers to direct JUDGE DREDD and SPICE WORLD, wise choices both), although he did reportedly attempt to mount quite a few. It took until 2019 for a new Stanley feature to appear: COLOR OUT OF SPACE, adapted from H.P. Lovecraft’s classic 1927 tale “The Colour out of Space.” Co-scripted by Stanley’s frequent writing partner Scarlett Amaris, it doesn’t approach the brilliance of DUST DEVIL, nor the transcendent eeriness of Lovecraft’s story (which was previously adapted in DIE, MONSTER, DIE! and DIE FARBE), but is worthwhile nonetheless.

In Lovecraft’s fictional Massachusetts province of Arkham, an alpaca enthusiast (Nicolas Cage) lives in a forest mansion with his wife (Joely Richardson) and three children, whose ranks include a Wicca-obsessed teenage girl (Madeleine Arthur) and her stoner brother (Brendan Meyer). After a meteor crashes into the Gardner’s front yard one night strange vegetation sprouts up, otherworldly animals and insects appear, Richardson’s flesh begins mutating, Cage’s alpacas transform into a vast multi-headed creature and Cage himself goes mad(der).

In Lovecraft’s fictional Massachusetts province of Arkham, an alpaca enthusiast (Nicolas Cage) lives in a forest mansion with his wife (Joely Richardson) and three children, whose ranks include a Wicca-obsessed teenage girl (Madeleine Arthur) and her stoner brother (Brendan Meyer). After a meteor crashes into the Gardner’s front yard one night strange vegetation sprouts up, otherworldly animals and insects appear, Richardson’s flesh begins mutating, Cage’s alpacas transform into a vast multi-headed creature and Cage himself goes mad(der).

What’s most striking about Richard Stanley’s direction, at least in the film’s first half, is its subtlety. It’s quite stately in its pacing and narrative development (thus putting it directly at odds with most of today’s genre fear), which makes it all the more disappointing when the film devolves into a noisy and undisciplined special effects blow out (in which sense it is indeed very much in keeping with today’s genre cinema).

A large part of the problem is that the Lovecraft source text is essentially a mood piece, which explains why a fully satisfying film adaptation has yet to appear. And yes, Stanley’s penchant for filching elements from past movies is very much in evidence throughout, with THE SHINING and John Carpenter’s THE THING both making their presence known. But THE COLOR OUT OF SPACE is on balance a worthwhile film, made by a talented maverick I’m glad to have back.

Here I’ll jump back in time to examine Stanley’s non-feature work. None of it is as worthwhile as HARDWARE, DUST DEVIL or  COLOR OUT OF SPACE, but there are some interesting works to be found amid the shorts, videos and documentaries to which Richard Stanley lent his talents.

COLOR OUT OF SPACE, but there are some interesting works to be found amid the shorts, videos and documentaries to which Richard Stanley lent his talents.

Stanley’s premiere short was RITES OF PASSAGE from 1983, made when Stanley was still a teenager. An imdb user summed up this 15 minute film thusly: “Whereas most lads in the 80s lucky enough to find themselves armed with a cine camera would have filmed their pals goofing around in badly applied zombie make-up…Stanley opted to make a stupefyingly dull drama about a man recalling a past life as a primitive who is killed by a wild animal.” The film is not unimpressive given its maker’s age and the incredibly primitive technical resources with which he was saddled, but it works better as a harbinger of things to come rather than a standalone work.

It was followed in 1985 with INCIDENTS IN AN EXPANDING UNIVERSE. This 45 minute mini-epic provided much of the impetus for HARDWARE in its brooding account of a young woman sculptress (Nicola Kench) and her soldier boyfriend (Charles Helps) caught up in a nightmarish future reality. There’s little in the way of a story, and the film is distractingly raggedy from a technical standpoint, as evinced by the poor sound mixing and mismatched visuals. It’s also pretentious (with dialogue like “I’m just brooding over the tyranny of clocks”) and (again) quite derivative, with flying cars and smoky interiors that are straight out of BLADE RUNNER, and outdoor battle scenes that look suspiciously like those of THE ROAD WARRIOR.

It was followed in 1985 with INCIDENTS IN AN EXPANDING UNIVERSE. This 45 minute mini-epic provided much of the impetus for HARDWARE in its brooding account of a young woman sculptress (Nicola Kench) and her soldier boyfriend (Charles Helps) caught up in a nightmarish future reality. There’s little in the way of a story, and the film is distractingly raggedy from a technical standpoint, as evinced by the poor sound mixing and mismatched visuals. It’s also pretentious (with dialogue like “I’m just brooding over the tyranny of clocks”) and (again) quite derivative, with flying cars and smoky interiors that are straight out of BLADE RUNNER, and outdoor battle scenes that look suspiciously like those of THE ROAD WARRIOR.

Stanley’s next short subject was a documentary: VOICE OF THE MOON (1990), a thirty minute portrait of Afghanistan during the Russian invasion of the late eighties. Much of it consists of grainy bolex-lensed footage of the daily life of the Afghanis (sort of like a low budget POWAQQATSI), complete with a dialogue-free soundtrack and an ever-present ambient score by HARDWARE and DUST DEVIL’S Simon Boswell. There are also scenes of warfare, but these are far too brief (Stanley admittedly only shot portions of a single battle) to make much of an impact. Final verdict: an appealingly scenic film, but also an exceedingly slight one.

BRAVE, from 1994, was essentially a 58 minute music video interpretation of the concept album of the same name by the British prog-rock band Marillon (following similarly oriented music video features like Duran Duran’s 1985 ARENA: AN ABSURD NOTION and the Pet Shop Boys’s 1987 IT COULDN’T HAPPEN HERE). Inspired by an actual incident in which a young woman was found wandering on a bridge in England, the songs attempt to flesh out the life of that mysterious woman, which in the band’s interpretation involves childhood abuse, epilepsy, heroin addiction and murder.

Stanley’s film places actress Josie Ayers in the lead role, haunted by a heckling off-screen voice that’s constantly thrusting her back and forth between the here-and-now and a featureless masked figure dominated dream world in which Stanley’s wildest imaginings are given full reign. The film is imaginative, but let down by its cheap 90-era video imagery; then as now, Stanley has always done his best work on celluloid.

THE SECRET GLORY, another documentary, hailed from 2001. An apparent “study” for a never made feature, it’s a look at the fortunes of Otto Rahn, the alleged inspiration for  RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK. Rahn’s life was spent searching for the Holy Grail, which Stanley suggests might be actually be a set of meteorological stones that “bleed” iron. Rahn ended up becoming a high-ranking Nazi officer but was eventually rejected, allegedly because he was descended from Jews and might have been a homosexual; he eventually froze to death while fleeing his overseers in a forest.

RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK. Rahn’s life was spent searching for the Holy Grail, which Stanley suggests might be actually be a set of meteorological stones that “bleed” iron. Rahn ended up becoming a high-ranking Nazi officer but was eventually rejected, allegedly because he was descended from Jews and might have been a homosexual; he eventually froze to death while fleeing his overseers in a forest.

Stanley, as elucidated in his DVD audio commentary, now feels he was given bad information about Rahn’s life, and that this film is a “work in progress”. Whatever THE SECRET GLORY might be, I found it off-putting initially, with its combination of archival footage and dramatic recreations held together entirely by after-the-fact interviews, but gradually came to appreciate its uniqueness.

Yet another documentary, THE WHITE DARKNESS, followed in 2002. It’s a 45-minute depiction of Haitian voodoo, featuring people performing ecstatic dances, apparently under the influence of spirits called Loa, and sacrificing animals, as well as American military forces looking to occupy the area and convert its inhabitants to Christianity. It’s this latter aspect that registered most strongly with me; particularly attention-grabbing are the final scenes, in which Stanley and his crew are threatened by apathetic Marines.

THE SEA OF PERIDITION is an eight minute short. It was once again intended as the impetus for a feature that was never made, and stands as the most interesting of Stanley’s non-documentary shorts. It’s far from coherent, but coherency doesn’t appear to have been Stanley’s goal in this brilliantly visualized depiction of a young woman cosmonaut (Maggie Moor) traversing the surface of Mars who enters a cavern…inside which things get very weird indeed.

Stanley’s next short film was part of THE THEATRE BIZARRE, a horror anthology from 2011 with contributions from Buddy Giovinazzo, Tom Savini, Karim Hussain, David Gregory, Jeremy Kasten and Douglas Buck. Stanley’s segment, alas, was the most pointless and nonsensical of the bunch, an H.P. Lovecraft inspired goof featuring Lucio Fulci regular Catriona MacColl and a silly-looking toad monster. (For the record, Giovinazzo’s contribution, a stylish account of marital strife set within the confines of a tiny apartment, was the best.)

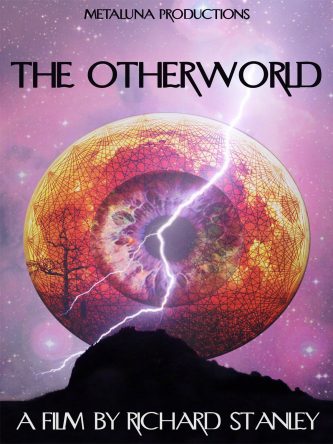

Finally we have the 105 minute THE OTHERWORLD [L’AUTRE MONDE]  from 2013, the most ambitious of Stanley’s documentaries. “This is the story of the strangest thing that ever happened to me” claims Richard Stanley himself at the beginning of this film. It explores Montsegur, a mountain region in the south of France where, according to legend, the supernatural holds sway in the form of Virgin Mary sightings, UFOs and interdimensional travel. Stanley and his cohort Scarlett Amaris claim to have once seen a spectral woman in Montsegur, apparently an incarnation of the Goddess who once ruled the Earth; Stanley and Amaris returned numerous times but only experienced one more such sighting, and now worry they’ll never have another.

from 2013, the most ambitious of Stanley’s documentaries. “This is the story of the strangest thing that ever happened to me” claims Richard Stanley himself at the beginning of this film. It explores Montsegur, a mountain region in the south of France where, according to legend, the supernatural holds sway in the form of Virgin Mary sightings, UFOs and interdimensional travel. Stanley and his cohort Scarlett Amaris claim to have once seen a spectral woman in Montsegur, apparently an incarnation of the Goddess who once ruled the Earth; Stanley and Amaris returned numerous times but only experienced one more such sighting, and now worry they’ll never have another.

As a history lesson THE OTHERWORLD is reasonably interesting, but as a piece of filmmaking it’s not very invigorating. It’s marred by a familiar Stanley movie complaint: a lot of derivative content, with visuals lifted rather blatantly from BARAKA (1992) and John Carpenter’s PRINCE OF DARKNESS (1987).

The good news is now that Richard Stanley is “back” there’s hope that he may yet create the career-defining masterpiece that has thus far eluded him—but even if he doesn’t we’re still left with a mighty interesting collection of films, some of which, obviously, are much better than others.