The untimely demise of film director Jonathan Demme on April 26, 2017 has inspired a number of obituaries. All, unsurprisingly, have been downright orgasmic about his accomplishments, and it’s true that Demme was one of America’s greatest filmmakers, with a relaxed, unpretentious mastery of the medium that produced some authentically great films. Unfortunately, it’s also a fact that Demme turned out some real clunkers in his day. My point? That this obituary is going to be a bit less effusive than the others, so if you’re expecting unbroken praise than you’d best stop reading now!

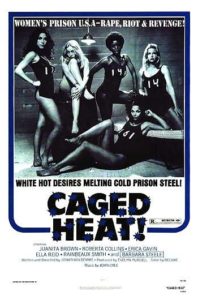

A former publicist, Demme got his filmmaking start, as did so many other directors of his era, with Roger Corman, for whom he made memorable exploitation flicks like the witty women-in-prison programmer CAGED HEAT (1974), the freewheeling crime saga CRAZY MAMA (1975) and the violent revenge drama FIGHTING MAD (1976). These films, along with ANGELS HARD AS THEY COME (1971), THE HOT BOX (1972) and BLACK MAMA WHITE MAMA (1973), all of which Demme scripted, show a real affinity for exploitation moviemaking that never entirely left him (Demme was said to be a longtime subscriber to the late Gore Gazette horror-exploitation movie review zine).

A former publicist, Demme got his filmmaking start, as did so many other directors of his era, with Roger Corman, for whom he made memorable exploitation flicks like the witty women-in-prison programmer CAGED HEAT (1974), the freewheeling crime saga CRAZY MAMA (1975) and the violent revenge drama FIGHTING MAD (1976). These films, along with ANGELS HARD AS THEY COME (1971), THE HOT BOX (1972) and BLACK MAMA WHITE MAMA (1973), all of which Demme scripted, show a real affinity for exploitation moviemaking that never entirely left him (Demme was said to be a longtime subscriber to the late Gore Gazette horror-exploitation movie review zine).

Those early films also demonstrate a rowdy comedic sensibility that was given full vent in 1977’s CITIZEN’S BAND/HANDLE WITH CARE, Demme’s first “legitimate” film. A freeform Altman-esque riff on the CB radio craze of the seventies, it’s a raggedy and low budget yet quite engaging piece of work that still holds up. Demme’s next film, the 1979 Roy Scheider headlined suspensor LAST EMBRACE, was even better, with a funky sense of humor subtly offsetting, but never overwhelming, the thriller business. Clearly this was a filmmaker whose talents were far from ordinary, as was proven by Demme’s next film.

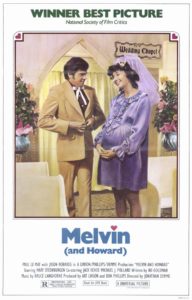

1980’s MELVIN AND HOWARD may well be Jonathan Demme’s masterpiece. A dramatization of the real-life case of Melvin Dumar, a Las Vegas everyman who claimed to have given an  elderly Howard Hughes a ride home one night, which apparently led to the latter leaving Dumar his fortune, the film marks Demme’s maturation as a filmmaker, being a fully realized, confident and inventive piece of filmmaking that satisfies in spite of an unresolved and rather bleak narrative (the authenticity of Hughes’ alleged will was never proven, and Melvin Dumar, as the film makes clear, never saw a dime of the fortune he claimed was his). Much of the tone and style of MELVIN AND HOWARD were reportedly set by its initial director Mike Nichols, who left the project because his choice for the role of Howard, Al Pacino(!), was nixed by Universal. Demme wisely went with the less starry Paul Le Mat, thuds proving that in addition to his many other talents he had a real gift for casting.

elderly Howard Hughes a ride home one night, which apparently led to the latter leaving Dumar his fortune, the film marks Demme’s maturation as a filmmaker, being a fully realized, confident and inventive piece of filmmaking that satisfies in spite of an unresolved and rather bleak narrative (the authenticity of Hughes’ alleged will was never proven, and Melvin Dumar, as the film makes clear, never saw a dime of the fortune he claimed was his). Much of the tone and style of MELVIN AND HOWARD were reportedly set by its initial director Mike Nichols, who left the project because his choice for the role of Howard, Al Pacino(!), was nixed by Universal. Demme wisely went with the less starry Paul Le Mat, thuds proving that in addition to his many other talents he had a real gift for casting.

1981’s WHO AM I THIS TIME? isn’t a movie, although it plays like an especially good one. It was a 54 minute episode of AMERICAN PLAYHOUSE, adapted from a Kurt Vonnegut story about a small-town production of A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE starring two odd individuals, played by Susan Sarandon and Christopher Walken. The latter is at his volatile and unpredictable best as a social misfit who only really comes alive when performing, and Demme compliments his work with characteristically perceptive yet eccentric filmmaking; the unorthodox use of close-ups in the sequence in which Sarandon and Walken meet at an audition is particularly representative of Demme’s unique sensibilities.

Next came the disastrous SWING SHIFT in 1984, an ambitious Goldie Hawn vehicle crippled by post production editing that left us with a plodding and predictable, and so very un-Demme, film. The director’s cut work print, which has been making the rounds of the greymarket circuit, solves many of the film’s issues, but not all.

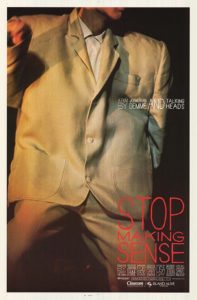

One of Demme’s most famous films, the Taking Heads concert documentary STOP MAKING SENSE, debuted that same year. I’ve always found the film overrated, with much of its enjoyment emerging from the design and costumes created by the band’s irrepressible headliner David Byrne (who turned to filmmaking himself in 1986’s TRUE STORIES) rather than the filmmaking. Demme, at least, was smart enough to document Taking Heads’s antics with a minimum of flashy editing and spastic camerawork (tendencies that today’s hyperactive videographers would do well to emulate). STOP MAKING SENSE was popular enough that it turned Demme into a sought-after music documentarian, as evinced by his subsequent concert docs STOREFRONT HITCHCOCK (1998), KENNY CHESNEY: UNSTAGED (2012), ENZO AVITABILE MUSIC LIFE (2012) and two Neil Young performance films.

most famous films, the Taking Heads concert documentary STOP MAKING SENSE, debuted that same year. I’ve always found the film overrated, with much of its enjoyment emerging from the design and costumes created by the band’s irrepressible headliner David Byrne (who turned to filmmaking himself in 1986’s TRUE STORIES) rather than the filmmaking. Demme, at least, was smart enough to document Taking Heads’s antics with a minimum of flashy editing and spastic camerawork (tendencies that today’s hyperactive videographers would do well to emulate). STOP MAKING SENSE was popular enough that it turned Demme into a sought-after music documentarian, as evinced by his subsequent concert docs STOREFRONT HITCHCOCK (1998), KENNY CHESNEY: UNSTAGED (2012), ENZO AVITABILE MUSIC LIFE (2012) and two Neil Young performance films.

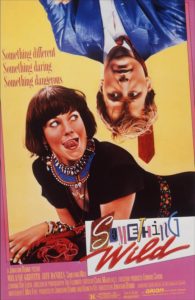

Next came the brilliant SOMETHING WILD. It remains one of Demme’s standout works, with an altogether strange, indeed near-surreal mixture of funk and mirth that for me puts it in the league of the same year’s BLUE VELVET. SOMETHING WILD was widely, and unfairly, criticized for its alleged tonal shift, with the first half being a breezy comedy about businessman Jeff Daniels and bohemian gal Melanie Griffith on a free-spirited crime spree, and the second a violent suspensor dominated by a debuting Ray Liotta as one of the screen’s great  psychopaths. Certainly there is a definite shift from one half of SOMETHING WILD to the other, but one that I’d argue is narrative rather than tonal; the film may turn dark and violent, but, intriguingly enough, it never quite loses the funky vibe of the early scenes.

psychopaths. Certainly there is a definite shift from one half of SOMETHING WILD to the other, but one that I’d argue is narrative rather than tonal; the film may turn dark and violent, but, intriguingly enough, it never quite loses the funky vibe of the early scenes.

The 1988 Michelle Pfeiffer starrer MARRIED TO THE MOB isn’t much, but it did prove that for all his quirks Demme knew how to craft a commercial audience-friendly entertainment without losing his personal touch. That talent would be used most lucratively two years later, in Demme’s next and most famous film.

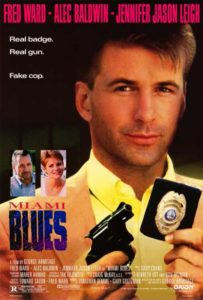

But before discussing that behemoth I’ll have to mention MIAMI BLUES, an unheralded gem from 1990 that Demme produced for his longtime pal George Armitage (another seventies exploitation movie veteran who directed PRIVATE DUTY NURSES, HIT MAN and VIGILANTE FORCE). I don’t know how much Demme actually contributed to MIAMI BLUES, but it sure  plays like a Demme film in its exuberant mixture of quirky comedy and extreme violence, all masterly visualized by Demme’s favorite cinematographer, the great Tak Fujimoto. More so even than SOMETHING WILD, MIAMI BLUES represents the logical extension of the exploitation flicks with which Demme and Armitage got their start, being an unapologetically down-and-dirty product pulled off with the verve and professionalism of seasoned masters.

plays like a Demme film in its exuberant mixture of quirky comedy and extreme violence, all masterly visualized by Demme’s favorite cinematographer, the great Tak Fujimoto. More so even than SOMETHING WILD, MIAMI BLUES represents the logical extension of the exploitation flicks with which Demme and Armitage got their start, being an unapologetically down-and-dirty product pulled off with the verve and professionalism of seasoned masters.

Onto SILENCE OF THE LAMBS, a film that should need no introduction. I’ll admit I’ve always been lukewarm toward it. It’s certainly a good movie that, like MARRIED TO THE MOB, presents many recognizable Demme quirks in a solidly commercial context, in addition to further evincing his spot-on eye for casting (with Jodie Foster and Anthony Hopkins chosen for the lead roles at a time when both were considered box office poison). Yet I’ve always preferred Michael Mann’s stylish and unnerving MANHUNTER, to which SILENCE was an unacknowledged sequel. SILENCE also introduced a number of annoying tendencies that would come to define Demme’s films, the trademarked Demme Close-Up (in which actors are directed to stare meaningfully at each other in place of expository dialogue) in particular.

Such close-ups littered 1993’s PHILADELPHIA, which began Demme’s socially conscious (read: politically correct) period. The flick, starring Tom Hanks as a gay lawyer with AIDS who sues his homophobic employer (a perpetually smirking Jason Robards) for wrongful termination, is precisely the sort of “important” picture Hollywood likes to pat itself on the back for making, even though it isn’t very good (the outcome of Hanks’ lawsuit is never in any doubt, nor his ultimate fate, which is presented in a shockingly offhand manner). The film’s saving grace is Demme’s consistently colorful and inventive filmmaking, which delivers some arrestingly odd angles and compositions, as well as one of the all-time great opening credits sequences.

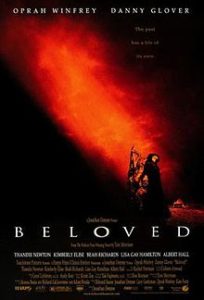

BELOVED followed in 1998. An adaptation of Toni Morrison’s Pulitzer Prize winning novel that was produced by and starring Oprah Winfrey, it’s one of Demme’s most vexing and difficult works. BELOVED isn’t a bad film by any means, but it is strange, incoherent, overlong (three hours!) and often downright artsy—and those aforementioned Demme Close-Ups are allowed to run riot. I claimed upfront that one of Demme’s virtues as a filmmaker was his “unpretentious” touch—here, then, is the exception.

It’s understandable that after such a heavy film Demme would turn to more lighthearted fare, but 2002’s THE TRUTH ABOUT CHARLIE, a remake of CHARADE (1963) that attempted to pay homage to the French new wave films of the 1960s in the guise of a commercial comedy, was plain awful. I’ve often said that my favorite Jonathan Demme film of 2002 was PUNCH-DRUNK LOVE, written and directed by Paul Thomas Anderson. An admitted Demme fanatic, Anderson provided a formally audacious romantic comedy whose violent edge put it in the company of SOMETHING WILD. THE TRUTH ABOUT CHARLIE, by ironic contrast, plays like someone doing a bad imitation of a Jonathan Demme movie.

2004’s THE MANCHURIAN CANDIDATE was another failed remake. The original MANCHURIAN CANDIDATE was about a presidential candidate brainwashed by Manchurian communists, whereas in Demme’s version the title refers to a corrupt corporation apparently meant to be a stand-in for the Dick Chaney run Halliburton. The result is once again dreary and unexciting, with few redeeming elements.

Following this Demme claimed he was ditching fictional features in favor of documentaries. Given how THE TRUTH ABOUT CHARLIE and THE MANCHURIAN CANDIDATE turned out, I can fully understand Demme’s decision to abandon scripted cinema. His documentaries, which include SWIMMING TO CAMBODIA (1987), COUSIN BOBBY (1992), THE ARGONOMIST (2003) and JIMMY CARTER MAN FROM PLAINS (2007), are all solid films, but lack the quirky brilliance of Demme’s pre-2000 fictional films—and anyway, he didn’t stick with his documentary-only vow for very long.

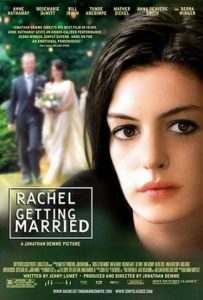

2008’s RACHEL GETTING MARRIED marked Demme’s return to non-documentary filmmaking and, despite the puzzlingly orgiastic reception it got from many critics, is middling at best. It’s another Demme product that can be described as Altmanesque, although the Robert Altman film it most resembles is A WEDDING, one of the maestro’s less successful efforts. To be sure, RACHEL GETTING MARRIED contains some terrifically perceptive moments, but it’s crippled by the fact that the leading role, essayed by Anne Hathaway, is (in a most un-Demme development) hopelessly miscast.

2008’s RACHEL GETTING MARRIED marked Demme’s return to non-documentary filmmaking and, despite the puzzlingly orgiastic reception it got from many critics, is middling at best. It’s another Demme product that can be described as Altmanesque, although the Robert Altman film it most resembles is A WEDDING, one of the maestro’s less successful efforts. To be sure, RACHEL GETTING MARRIED contains some terrifically perceptive moments, but it’s crippled by the fact that the leading role, essayed by Anne Hathaway, is (in a most un-Demme development) hopelessly miscast.

As for Demme’s more recent films, which include the 2013 Henrik Ibsen adaptation A MASTER BUILDER, the Diablo Cody scripted 2015 comedy RICKI AND THE FLASH and 2016 concert documentary JUSTIN TIMBERLKE + THE TENNESSEE KIDS (really?), I didn’t bother seeing them. Yes, I remain a Demme fan, but I got tired of being let down.

So okay: Mr. Demme’s filmography isn’t entirely without its lesser offerings. It still, however, contains LAST EMBRACE, MELVIN AND HOWARD, WHO AM I THIS TIME?, SOMETHING WILD, MIAMI BLUES and THE SILENCE OF THE LAMBS, which more than testify to the unique and unprecedented brilliance of Jonathan Demme, a filmmaker whose likes we won’t be seeing again.