1991 was a banner year for literary horror. While the advent of the nineties officially marked the start of the genre’s decade-long decline, some powerful and innovative horror novels appeared in ‘91 that have stood the test of time. There was Brett Easton Ellis’ AMERICAN PSYCHO, Theodore Roszak’s FLICKER, Dennis Cooper’s FRISK, John Skipp and Craig Spector’s THE BRIDGE, Kathe Koja’s THE CIPHER (which kicked off Dell’s seminal Abyss line) and THE BRAVE by the late Gregory McDonald, perhaps the most starkly powerful novel of them all.

According to its own cover description, THE BRAVE “contains episodes that will shock even the most jaded reader: it is not for the weak at heart.” It appeared in October of ‘91, several months after AMERICAN PSYCHO and FRISK, and any controversy THE BRAVE might engender had apparently been used up in all the outrage that greeted the above novels. Outrage is something that might have benefited THE BRAVE, which came and went with nary a whimper. Published in hardcover by Barricade Books, it never made it to paperback in the U.S., and is now extremely difficult to come by.

THE BRAVE is a shattering tale, and quite likely a prescient one. The protagonist is the kind-hearted Rafael, an unemployable 21-year-old drunk who as the novel opens is talking to some sleazy guys about a job. This “job” entails Rafael being tortured to death in a snuff film, delineated in a third chapter so appalling the author forewarns us about it in a nonfiction forward (“the author realizes this chapter is particularly strong and repulsive…He wishes he could have avoided writing that particular chapter”). Although the imminent fingernail ripping, eyeball gouging and penis chopping are only described by Rafael’s would-be employers, said descriptions are so horrid they suffuse the remainder of the novel like a shroud.

Rafael, it transpires, lives in an abandoned motor home with his wife and three young children. Their “neighborhood” is Morgantown, a filthy hillside located next to a garbage dump whose rich owners shoot anyone caught foraging. With no hope of employment, the snuff film gig seems like a good idea to Rafael, as it will bequeath a promised $30 grand to his family so they can move away—even though, as Rafael’s wife makes clear, all that really awaits them outside Morgantown is more hopelessness. Nor does the illiterate Rafael understand that the contract given him, which allegedly lays out the details of his employment, is complete gibberish.

We learn all this during a four-day furlough Rafael is given to put his affairs in order. Rafael’s final days are very much in keeping with his overall existence: bleak and uneventful. Unwilling to tell his wife or his neighbors about his new job, he stagnates, and is briefly imprisoned on suspicion of a local robbery. Eventually the fateful day rolls around and Rafael boards a bus back to the city, with the incoherent contract described above left for his wife to find.

Yes, this is a profoundly grim piece of work, but it’s also compulsively readable. Gregory MacDonald’s prose, developed in his better-known FLETCH and FLYNN crime sagas, is spare and focused to a fault, making for sharp yet disarmingly inviting prose. As with AMERICAN PSYCHO, the central concept was doubtless intended as a metaphor for the exploitation of the have-nots by the haves, yet these days, with soaring unemployment, widespread poverty and the dominance of (so-called) reality television, the idea of a guy sacrificing himself in a snuff film doesn’t seem all that farfetched.

As a horror novel, one of THE BRAVE’S most striking qualities is that not a whole lot actually happens in its 216 pages (it concludes before the scheduled killing occurs), yet its effect on the reader is profound and long-lasting. Describing a screenplay adaptation of THE BRAVE, NATURAL BORN KILLERS producer Jane Hamsher called it “the most disturbing thing I’ve ever read. I had nightmares all night…,” which adequately sums up the novel’s impact.

THE BRAVE may have never cracked the bestseller lists, but it made a mark. In France, where it was titled RAFAEL, DERNIERS JOURS (RAFAEL, LAST DAYS), it won the Trophees 813 award for Best Foreign novel, and a European critic proclaimed it “one of the two or three greatest novels ever written.” Back in its native land THE BRAVE had its greatest impact on the movie industry; the novel, with its studied uneventfulness, seems ill-suited to a film adaptation, and yet it was snapped up by Hollywood almost immediately.

The initial attempt at filming THE BRAVE was by Aziz Ghazal, the former manager of the USC film school equipment room (and producer of 1987’s ZOMBIE HIGH). Scripted by Paul McCudden, the project attracted interest from Oliver Stone, Jodie Foster and Touchstone Pictures. But the production ultimately fizzled out (a not-uncommon occurrence) and in late 1993 a despondent Ghazal killed his ex-wife and daughter and then shot himself in the head. This tragedy fostered the belief that was project was “cursed,” yet it was revived a few years later.

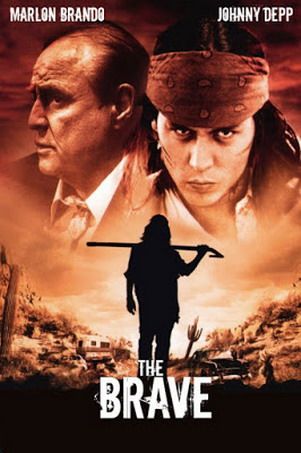

The so-called savior was Johnny Depp, who succeeded in filming THE BRAVE in 1997, with a newly written script and himself in the lead role. Some people like the film. I don’t.

It’s hard to tell if Depp has any real talent as a director, as THE BRAVE is essentially a glorified student film. Depp had just completed filming on Emir Kusturica’s phantasmagoric comedy ARIZONA DREAM, and THE BRAVE has a similarly freewheeling vibe (and no surprise, as the cinematographer Vilko Filac, production designer Miljen Kreka Kljakovic and art  director Branimir Bane Babic were all recruited from Kusturica’s film). The problem with this approach is that it’s at odds with the material, which is resolutely gritty and unforgiving. The film’s Morgantown, for starters, is a Fellini-esque wonderland packed with loveable eccentrics, which makes it difficult to understand why the protagonist would want to sacrifice himself.

director Branimir Bane Babic were all recruited from Kusturica’s film). The problem with this approach is that it’s at odds with the material, which is resolutely gritty and unforgiving. The film’s Morgantown, for starters, is a Fellini-esque wonderland packed with loveable eccentrics, which makes it difficult to understand why the protagonist would want to sacrifice himself.

Other problems include a bad guys’ lair that’s wildly overdesigned (complete with flickering neon lighting and a dungeon-like cavern) and an unforgivably hammy cameo by Marlon Brando, who recycles his Colonel Kurtz shtick in his recitation of a rambling monologue about death (which ill-advisedly takes the place of the novel’s winsome third chapter). There’s also a climactic fight scene shamelessly copied from MIDNIGHT EXPRESS and a ludicrously overwrought conclusion that, in direct opposition to the novel’s pared-down simplicity, all-but bludgeons us in delineating the tragedy of its hero’s existence.

Unsurprisingly, Depp’s film bombed at the ‘97 Cannes Film Festival, and has yet to attain a U.S. release (although it’s readily available in bootleg form and can be seen in its entirety on YouTube). It did nothing to improve the fortunes of Gregory McDonald’s novel, which despite its qualities appears destined for a fate similar to that of its tragic protagonist…or maybe not. Secondhand copies of the novel are still extant, and I hereby urge you to search one out!