Russia’s Konstantin Lopushansky is one of the greatest filmmakers you’ve never heard of. He’s known in the Western world for his 1986 masterpiece LETTERS FROM A DEAD MAN, although even that particular film has become quite obscure, having never been released in the U.S. on VHS or DVD. As for his other films, they’re all-but nonexistent in these parts.

From what I gather, Lopushansky isn’t particularly well respected in his native Russia, where his films are widely criticized for their lack of humor and overly similar subject matter. Neither criticism is entirely groundless, but Lopushansky’s films are still among the most bold and poetic of any filmmaker.

Konstantin Lopushansky was mentored by the great Andrei Tarkovsky. Lopushansky worked as a production assistant on the maestro’s 1979 masterpiece STALKER, which evidently had a sizeable effect on the young filmmaker. One of his earliest stabs at filmmaking, the 1980 short SOLO, was directly overseen by Tarkovsky.

Konstantin Lopushansky was mentored by the great Andrei Tarkovsky. Lopushansky worked as a production assistant on the maestro’s 1979 masterpiece STALKER, which evidently had a sizeable effect on the young filmmaker. One of his earliest stabs at filmmaking, the 1980 short SOLO, was directly overseen by Tarkovsky.

In SOLO the young Lopushansky created a near-perfect 29-minute distillation of his subsequent obsessions. Lensed in hazy black and white, the film is set in Leningrad during the 1942 blockade . Shell-shocked survivors huddle together in collapsing shacks while occasionally foraging in the bleak snow-bound world outside, with the gloom eventually lessened by a ragtag orchestra performed for an audience of one.

SOLO doesn’t quite approach the brilliance of Lopushansky’s two subsequent films but is stunningly effective nonetheless, showcasing a skilled and distinct filmmaking sensibility. That’s evident in the art direction, which is grittily impressive and disturbingly convincing. So too the all-pervading mood of poetic despair.

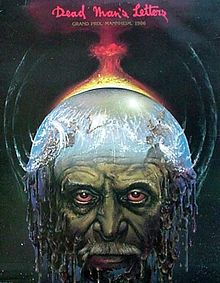

Lopushansky would enhance that mood in 1986’s astonishing LETTERS FROM A DEAD MAN (PISMA MYORTVOGO CHELOVEKA), a  shattering yet profoundly moving dramatization of the aftermath of an all-out nuclear war. Civilization has been devastated, with the scattered survivors subsiding in dimly-lit, rubble-strewn hovels. The radiation choked outside world is even more horrific, with massive piles of refuse and dead bodies scattered everywhere. It’s one of the most grimly convincing post nuke environments I’ve ever seen, a minutely imagined universe visualized in different tints of black and white, which gives the proceedings just the right touch of otherworldliness.

shattering yet profoundly moving dramatization of the aftermath of an all-out nuclear war. Civilization has been devastated, with the scattered survivors subsiding in dimly-lit, rubble-strewn hovels. The radiation choked outside world is even more horrific, with massive piles of refuse and dead bodies scattered everywhere. It’s one of the most grimly convincing post nuke environments I’ve ever seen, a minutely imagined universe visualized in different tints of black and white, which gives the proceedings just the right touch of otherworldliness.

The central character is a Nobel Prize winning professor who writes letters to his dead son while desperately trying to frame his situation in logical, easy-to-grasp terms. He can’t, of course, as he and his doomed companions are trapped in a nightmare of madness and despair.

LETTERS FROM A DEAD MAN, partially scripted by Boris Strugatsky of the Strugatsky brothers (of STALKER), may be harshly realistic, but it also has a poetic and ethereal angle to it, and concludes on an unexpected note of (possible) hope. Andrei Tarkovsky’s influence is evident in the long shots, the measured pacing and the oft-dreamlike atmosphere; it’s the film that, if you ask me, Tarkovsky’s THE SACRIFICE (also released in 1986, and also concerned with the consequences of a nuclear war) should have been.

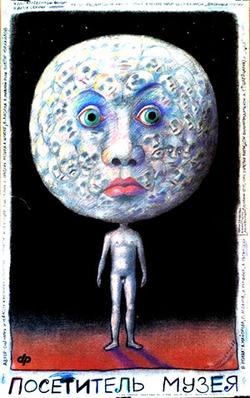

Topping such an auspicious effort seems foolhardy, if not completely impossible, yet 1989’s VISITOR TO A MUSEUM (POSETITEL MUZEYA) handily accomplished that feat. It’s a sequel of sorts, set in an even more expansive post-apocalyptic future in which mountains of scattered debris dot the landscape in the every direction and the population consists of human oddities of every stripe.

Topping such an auspicious effort seems foolhardy, if not completely impossible, yet 1989’s VISITOR TO A MUSEUM (POSETITEL MUZEYA) handily accomplished that feat. It’s a sequel of sorts, set in an even more expansive post-apocalyptic future in which mountains of scattered debris dot the landscape in the every direction and the population consists of human oddities of every stripe.

The protagonist is a young man who arrives at a burned-out beachfront hotel in search of a museum submerged beneath the waves. Much of the film’s first half consists of an extremely slow, contemplative sequence of events that again show Lopushansky’s debt to Tarkovsky. The final hour, however, is something else entirely: a hallucinatory Christ parable that has the protagonist become an unwitting savior to a vast congregation of freaks. He drifts into an increasingly psychotic reality, ending up a babbling recluse crying out to an unseen deity who offers little in the way of a response.

The proceedings are somewhat less than subtle in their overbearing Christian symbolism, but they also demonstrate a visual mastery that places Lopushansky in the front ranks of Russian filmmakers. I’ve no idea what the budget was, but it looks to have been substantial, with insanely extravagant art direction, several hundred extras, and wide shots in which nature itself—in the form of lightning, crashing waves and the sun emerging from behind clouds—appears fully complaint with the director’s vision.

1994’s RUSSIAN SYMPHONY (RUSSKAYA SIMFONIYA) was the third in Lopushansky’s so-called apocalypse trilogy (which actually wound up a  quartet), and the least of the three in many respects. Once again Lopushansky crafts a dense, Tarkovsky inspired account of faith and despair in a sumptuously detailed apocalyptic future. The protagonist is a desperate man looking to save the children of an orphanage from rising flood waters suffusing Russia, but he can’t find anyone to help him amid a populace increasingly mired in riots and insanity.

quartet), and the least of the three in many respects. Once again Lopushansky crafts a dense, Tarkovsky inspired account of faith and despair in a sumptuously detailed apocalyptic future. The protagonist is a desperate man looking to save the children of an orphanage from rising flood waters suffusing Russia, but he can’t find anyone to help him amid a populace increasingly mired in riots and insanity.

Lopushansky’s magisterial visual panoramas are once again stunning (a climactic solar eclipse and mock 19th Century battle in particular), as are his impeccably choreographed crowd scenes, featuring what look like thousands of extras. The problem is that thematically there’s really nothing here the previous films didn’t already cover, including the narrative arc that has the protagonist becoming a (false) savior to gullible flocks of people before eventually finding salvation (of a sort) in faith—just as the guy from VISITOR TO A MUSEUM did. But while that film expanded on the themes of its predecessor, RUSSIAN SYMPHONY merely rehashes them.

RUSSIAN SYMPHONY was generally well received, winning a jury prize at the Berlin Film Festival (an award that should have gone to VISITOR OF A MUSEUM), but it showed the limitations of Lopushansky’s apocalyptic bent. His next feature, 2001’s non futuristic TURN OF THE CENTURY (KONETS VEKA), was a thematic break from the previous films, being a staid and over-stylized drama about a depressed old woman led by her materialistic daughter to an institute where an aged doctor attempts to wipe the old woman’s memory. The mystical elements that suffuse the final third (in which fantasies and hallucinations increasingly overtake the proceedings), as well as the overbearing political angle (the film is set during a real-life strike in Moscow of 1993), will be familiar to viewers of the previous films, but otherwise it’s difficult to discern any trace of Lopushansky’s genius in TURN OF THE CENTURY.

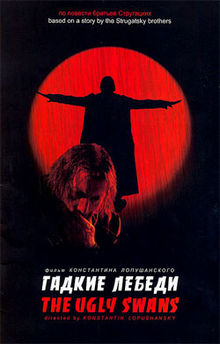

For his next film, 2006’s UGLY SWANS (GADKIE LEBEDI), Lopushansky returned to the science fiction tinged dystopias of the apocalypse trilogy, and emerged with a fairly inspired work. Based on a story by the Strugatsky brothers, the film is another bleak affair set in yet another war-ravaged future world. Here a group of mutants, damaged in some unexplained chemical accident, have set up a school of sorts where they teach kidnapped youngsters how to be geniuses and levitate. The protagonist is a UN appointee sent to investigate the school who has a personal stake in the trip: his daughter is one of the children being “taught.”

For his next film, 2006’s UGLY SWANS (GADKIE LEBEDI), Lopushansky returned to the science fiction tinged dystopias of the apocalypse trilogy, and emerged with a fairly inspired work. Based on a story by the Strugatsky brothers, the film is another bleak affair set in yet another war-ravaged future world. Here a group of mutants, damaged in some unexplained chemical accident, have set up a school of sorts where they teach kidnapped youngsters how to be geniuses and levitate. The protagonist is a UN appointee sent to investigate the school who has a personal stake in the trip: his daughter is one of the children being “taught.”

What ensues is brainy and haunting in the best Lopushansky tradition, and concludes with a hint of CLOCKWORK ORANGE-ish dark comedy when the kids are rescued from the school and made to watch moronic TV programs in order to fit in with mainstream society. The budget was evidently sparser than those of Lopushansky’s previous films, which is evident in the cut-rate production design and cheesy CGI. Yet Lopushansky’s visual genius is very much in evidence: UGLY SWANS has an arresting red-hued color scheme and quite a few mind-tugging hallucinatory segues. All in all it’s a satisfying film, even if it doesn’t exactly cover new ground.