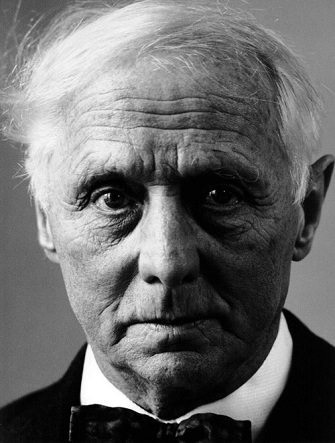

Max Ernst (1891-1976) is, after Salvador Dali, the most famous of the original surrealists. An artist of undeniable skill and vision, Ernst created many justifiably famous paintings in his lifetime, including “L’Ange Du Foyer” and “Europe after the Rain.” However, I believe Ernst’s supreme masterworks are his collage novels THE HUNDRED HEADLESS WOMAN (1929), A LITTLE GIRL DREAMS OF TAKING THE VEIL (1930) and A WEEK OF KINDNESS (1934).

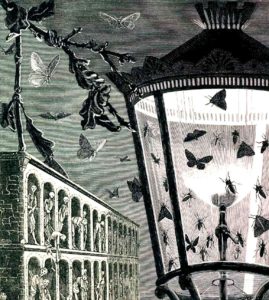

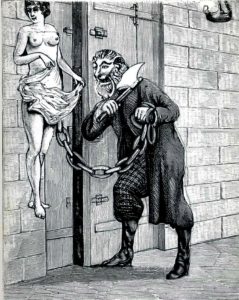

Ernst created these “novels” by cutting out sentimental woodcut illustrations and reconfiguring them into perverse and surreal collages. The results are seamlessly pasted together, so much so that it often seems difficult to imagine how these renderings could have possibly started out differently. Many other artists before and since have made similar attempts (see Freddie Baer’s ECSTATIC INCISIONS), but none of the collage work I’ve seen comes close to matching Ernst’s accomplishments.

Ernst created these “novels” by cutting out sentimental woodcut illustrations and reconfiguring them into perverse and surreal collages.

THE HUNDRED HEADLESS WOMAN [sic] (LE FEMME 100 TETES) was published in the US by George  Braziller in 1981, with English translations by Ernst’s widow Dorothea Tanning. It consists of 147 seemingly random collages grouped into nine “chapters.” Each collage has a quintessentially surreal caption below it—“The might-have-been Immaculate Conception,” “The charm of transportations and wounds will be increased in silence by boiling laundry,” “Loud chirpings of Sunday phantoms,” “So he who speculates the vanity of the dead remains the phantom of repopulation.” Among the pictures are a tiny statue grabbing a man’s crotch (with the caption “The exorbitant reward”); a woman’s nude torso draped around a guy’s neck; a fountain spouting from a top hat; a fishing net hauling in naked people; a man relaxing in a chair situated atop a crashing wave; a woman going down on a rendering of Cezanne; a “swamp of dreams” flowing through Paris.

Braziller in 1981, with English translations by Ernst’s widow Dorothea Tanning. It consists of 147 seemingly random collages grouped into nine “chapters.” Each collage has a quintessentially surreal caption below it—“The might-have-been Immaculate Conception,” “The charm of transportations and wounds will be increased in silence by boiling laundry,” “Loud chirpings of Sunday phantoms,” “So he who speculates the vanity of the dead remains the phantom of repopulation.” Among the pictures are a tiny statue grabbing a man’s crotch (with the caption “The exorbitant reward”); a woman’s nude torso draped around a guy’s neck; a fountain spouting from a top hat; a fishing net hauling in naked people; a man relaxing in a chair situated atop a crashing wave; a woman going down on a rendering of Cezanne; a “swamp of dreams” flowing through Paris.

…147 seemingly random collages grouped into nine “chapters.”

As for narrative continuity, that’s up to the individual reader to decipher for him/herself. Characters (identified by the captions) include a wise monkey who pops up periodically; Loplop the “Bird Superior,” a recurring figure in Ernst’s art who initially appears as a bird and later takes on the guise of a human; and the spectral Hundred Headless Woman (sic), who assumes many identities throughout the book–as one caption reads, “It’s enough for me to see the Hundred Headless Woman to know. It’s enough for you to demand an explanation, not to know.” That essentially sums up this maddening but altogether extraordinary work.

A LITTLE GIRL DREAMS OF TAKING THE VEIL (REVE D’ UNE PETITE FILLE QUI VOULUT ENTRER AU CARMEL) was again published in English by George Braziller and again with translations by Dorothea Tanning. It is in many ways the pinnacle of Ernst’s collage novels.

A LITTLE GIRL DREAMS OF TAKING THE VEIL (REVE D’ UNE PETITE FILLE QUI VOULUT ENTRER AU CARMEL) was again published in English by George Braziller and again with translations by Dorothea Tanning. It is in many ways the pinnacle of Ernst’s collage novels.

Unlike Ernst’s other books, A LITTLE GIRL DREAMS… contains a somewhat coherent narrative, being the blasphemous, erotic and schizophrenic dream of sixteen-year-old Marceline-Marie. A 5-page text introduction fills us in on the life of M-M before the dream, marked by a rape at age seven and a mystical episode four years later, in which she levitated in church and thereafter devoted her life to a religious vocation.

A LITTLE GIRL DREAMS… contains a somewhat coherent narrative, being the blasphemous, erotic and schizophrenic dream of sixteen-year-old Marceline-Marie.

Those things are all obliquely addressed in the dream that follows, consisting of 77 collages “explained” by surrealistic captions and divided into four chapters: “The Tenebreuse,” “The Hair,” “The Knife” (which the girl was holding during her levitation) and “The Celestial Bridegroom” (who she referenced during the episode). The cockeyed magic of THE HUNDRED HEADLESS WOMAN is once again in evidence, with the text in conjunction with the pictures creating unforgettable configurations.

The dream begins with a picture of the title character smooching her father—and a glass in the foreground obscuring the figures’ liplock. Two pages later Marceline-Marie literally splits in two, spending the remainder of the dream as Marceline and Marie. Marceline-Marie frequently has trouble distinguishing between her two selves, and on occasion even confuses herself with other characters, including an “indecent Amazon” and an “obscure beetle.” Marceline and Marie are frequently accosted by Father Dulac, who administered M-M’s first communion and who encourages both to “Follow me, my beauty, to the cracks in the walls…” At the end of each chapter M-M awakens to examine her bed clothes, and always finds her nightgown pulled up past her knees in “indecent” fashion.

The dream begins with a picture of the title character smooching her father—and a glass in the foreground obscuring the figures’ liplock. Two pages later Marceline-Marie literally splits in two, spending the remainder of the dream as Marceline and Marie. Marceline-Marie frequently has trouble distinguishing between her two selves, and on occasion even confuses herself with other characters, including an “indecent Amazon” and an “obscure beetle.” Marceline and Marie are frequently accosted by Father Dulac, who administered M-M’s first communion and who encourages both to “Follow me, my beauty, to the cracks in the walls…” At the end of each chapter M-M awakens to examine her bed clothes, and always finds her nightgown pulled up past her knees in “indecent” fashion.

As for the illustrations, they’re among the most densely layered and tantalizingly mysterious of all Ernst’s work.

As for the illustrations, they’re among the most densely layered and tantalizingly mysterious of all Ernst’s work. Stand-out images include a woman leaning out a window to address a pair of bodiless heads; a party stocked by billowing smoke, brawling men and decaying corpses; another depiction of Ernst’s alter ego Loplop, here a king attended to by a bird-headed sentry; a naked woman dancing amidst a swarm of crickets; bundles of hair sprouting from ship’s masts and the faces of pall-bearers (“the better to put you in your place, my child”); a man walking on water, exhorting shipwrecked sailors to “Come and admire the view from the top of the mast.” There are dozens more equally eerie, mind-bending sights on display, but most are frankly beyond my power to describe.

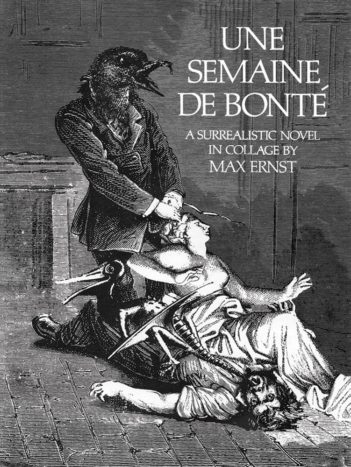

A WEEK OF KINDNESS (UNE SEMAINE DE BONTE), appeared in the US under the original French moniker in 1976, courtesy of Dover (the English  translation this time was by Stanley Appelbaum), and it at least is still in print. It was the last and most elaborate of Ernst’s experiments in collage, with 182 illustrations divided into seven parts. As the title suggests, the book is set over the course of a week (the “Kindness” part is obviously ironic), with each day based around an “Element” and “Example”. On Sunday that element is mud and the example is “The Lion of Belfort”—hence, each illustration features a man with a lion head.

translation this time was by Stanley Appelbaum), and it at least is still in print. It was the last and most elaborate of Ernst’s experiments in collage, with 182 illustrations divided into seven parts. As the title suggests, the book is set over the course of a week (the “Kindness” part is obviously ironic), with each day based around an “Element” and “Example”. On Sunday that element is mud and the example is “The Lion of Belfort”—hence, each illustration features a man with a lion head.

It was the last and most elaborate of Ernst’s experiments in collage, with 182 illustrations divided into seven parts.

Monday’s element and example is water, and so nearly everything on this day centers on flooding and/or pooled water. Tuesday’s example is the “Court of The Dragon,” meaning there’s a dragon or part of one appearing in every panel. We also see more examples of Loplop the bird-head, who all-but takes over on Wednesday, which features the book’s most striking illustrations: they all revolve around bird-headed people doing strange and pervy things (the cover image here is Oedipus!). On Thursday more bird-heads turn up, all of them roosters, the Example being “The Rooster’s Laughter.” On Friday we again see people with weird heads, this time Easter Island statues.

Saturday is the most abstract section, split into two parts. One is called “Three Visible Poems”, presenting several panels featuring bones, foliage and other ephemera stuck together. The other is “The Key to Songs,” which consists largely of floating women, making for a fitting end to the most overtly poetic of the three books. While it’s not my favorite of Ernst’s collage novels, A WEEK OF KINDNESS does close things out on a suitably ambitious note.

Saturday is the most abstract section, split into two parts. One is called “Three Visible Poems”, presenting several panels featuring bones, foliage and other ephemera stuck together. The other is “The Key to Songs,” which consists largely of floating women, making for a fitting end to the most overtly poetic of the three books. While it’s not my favorite of Ernst’s collage novels, A WEEK OF KINDNESS does close things out on a suitably ambitious note.

The shock and awe that initially greeted these books (they were vigorously denounced by the Nazis) has long since worn off, but the charm, beauty and sheer genius of their conception and execution have not. THE HUNDRED HEADLESS WOMAN, A LITTLE GIRL DREAMS OF TAKING THE VEIL and A WEEK OF KINDESS are all must-own grown-up picture books that have yet to be surpassed.