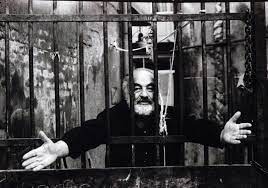

The way the media treats Sergei Paradjanov (1924-1990) and Andrei Tarkovsky, you’d think they were a tag-team. To be sure, these two were acclaimed filmmakers and longtime pals who struggled to create great cinema in the Soviet Union, and paid the price—imprisonment in Paradjanov’s case and exile in Tarkovsky’s. There, however, the similarities end.

…Longtime pals who struggled to create great cinema in the Soviet Union, and paid the price…

Paradjanov was a boisterous, life-loving individual, in stark contrast to the legendarily introverted and misanthropic Tarkovsky—and, unlike the staunchly Russian Tarkovsky, Paradjanov was born in Georgia and worked primarily in the Ukraine. Nor were their films as complimentary as they’re often claimed to be; see the 2003 documentary ANDREI TARKOVSKY & SERGEI PARDJANOV: ISLANDS, which meshes together footage from their respective films that only goes to prove just how dissimilar these two geniuses truly were.

A far better Paradjanov adjunct, in my view, was his longtime friend and sometime collaborator Yuri Ilyenko (1936-2010). These two, in contrast to Paradjanov and Tarkovsky, were actually quite similar in outlook, background and physical appearance (being hefty and imposing fellows), which may explain why their filmic collaborations were so few: quite simply, they were too much alike.

Ilyenko was born in Ukraine but grew up in Russia. He joined the Ukraine-based Dovzhenko Film Studios in 1963, and was invited to be the cinematographer of the Paradjanov helmed SHADOWS OF FORGOTTEN ANCESTORS/TINI ZABUTYKH PREDKIV (1964). The film, lensed in the Carpathian village of Kryvorivnia, is a swirl of visual exuberance that, judging by the subsequent filmographies of its director and cinematographer, can be said to have functioned as a collaboration between the two rather than the auteurist statement it’s often made out to be.

With SHADOWS Paradjanov introduced the avant-garde approach that would come to dominate his later filmography, yet what truly marks it out from his other films both earlier and later is its pictorial extravagance, which comes directly from Ilyenko.

Paradjanov was already something of a veteran when he made SHADOWS OF FORGOTTEN ANCESTORS. He began his filmmaking career in 1951 (after studying to be a singer and dancer) and helmed numerous Ukrainian melodramas that included ANDRIESH (1954) and UKRAINIAN RHAPSODY/UKRAINSKAYA RAPSODIYA (1961), all of which he later dismissed as “garbage.” Also, in a sign of things to come, he was arrested in the early 1950s, for “homosexuality,” by Soviet authorities (as he once stated, “I’m the only Soviet filmmaker to have been imprisoned under Stalin, Brezhnev and Andropov”). With SHADOWS Paradjanov introduced the avant-garde approach that would come to dominate his later filmography, yet what truly marks it out from his other films both earlier and later is its pictorial extravagance, which comes directly from Ilyenko.

The film concerns Ivan (the debuting Ivan Mykolaichuk) and Marichka (Ilyenko’s then-wife Larisa Kadochnikova), two youngsters from feuding tribes—Marichka’s tribe is rich and Ivan’s poor—who fall in love, conveyed via handheld camerawork that rarely ever stays sill and a riot of at times-bloody drama and arcane rituals. When Marichka drowns in a river Ivan is plunged into despair, as depicted by black and white photography and voice-over dialogue about his condition from the surrounding community. He eventually takes up with a woman named Palagna, but Marichka’s ghost continues to haunt him, forcing Palagna into the arms of Yurko, an evil magician.

The film is as much about the spirit of the Ukrainian people as it is an Eastern-centric ROMEO AND JULIET, with corn husking and ritual dances frequently taking center stage in an immersive riot of poetic symbolism (lambs are quite prevalent) and painterly tableaus. That most of those images will be incomprehensible to anyone not Ukrainian is beside the point, as Paradjanov and Ilyenko have created a fascinating and kinetic piece of cinema that showcases both artists at the top of their respective forms.

The film was rapturously received throughout the world. The reaction in its native land was likewise quite positive, with it having initiated the Ukrainian Poetic Cinema movement whose output includes Ilyenko’s feature directorial debut A SPRING FOR THE THIRSTY/KRYNYTSYA DLYA SPRAHLYKH (1965), Leonid Osyka’s THE STONE CROSS/KAMINNYY KHREST (1968), Boris Ivchenko’s THE LOST LETTER/PROPALA HRAMOTA (1972) and Ilyenko’s A STORY OF THE FOREST: MAVKA/LISOVA PISNYA. MAVKA (1981), in my view the true spiritual successor to SHADOWS OF FORGOTTEN ANCESTORS.

There were, however, early indicators of the dark days in store for this duo. SHADOWS’ lead actor Ivan Mykolaichuk was barred from working in the Soviet film industry for half a decade due to his participation in the film (with the official charge being that he was a “person of hostile ideology”), which furthermore was roundly condemned by the influential Moscow critic Mikhail Bleyman for its deviations from “Soviet Realism.”

The darkness accelerated with the 1968 release of Ilyenko’s second self-directed feature, the surreal and flamboyant Nikolai Gogol adaptation THE EVE OF IVAN KUPALO/VECHIR NA IVANA KUPALA, which was banned for eighteen years. Paradjanov’s 1969 masterwork SAYAT NOVA—in whose conception Ilyenko played a crucial (if indirect) role, with the film’s fixed camera style having been conceived in direct opposition to the kineticism of SHADOWS OF FORGOTTEN ANCESTORS—suffered an even worse fate, undergoing extensive recutting and a retitling (to THE COLOR OF POMEGRANATES), in addition to Paradjanov’s unjust 1973 internment in a labor camp, from which he wasn’t released until 1977.

Ilyenko wasn’t imprisoned for his films, but he was subjected to plenty of Soviet-sponsored strife. His 1971 film THE WHITE BIRD MARKED WITH BLACK/BILYY PTAKH Z CHORNOYU OZNAKOYU was, despite receiving the grand prize at the Moscow International Film Festival, banned (with the claim that it was “the most harmful movie that has ever been made in Ukraine, especially harmful to young people”), while production on his 1975 film DREAMING AND LIVING/MECHTAT I ZHIT was halted a reported 42 times during its filming and editing (resulting, according to Ilyenko’s own verdict, in a “Dead Film”).

Paradjanov, upon his 1977 parole, was exiled from the Soviet film community and arrested again in 1982. That imprisonment lasted a few months, after which, following a loosening up of Soviet restrictions, he made THE LEGEND OF SURAM FORTRESS/AMBAVI SURAMIS TSIKHITSA (1985) and ASHIK KERIB/ASHUG-KARIBI (1988), and, shortly before his demise, gathered together seven film scenarios that were eventually published in France as SEPT VISIONS (1992), and in America as SEVEN VISIONS (1998). Among those scenarios were five unrealized projects, in addition to his initial scenario for SAYAT NOVA and a quasi-autobiographical recounting of his second incarceration.

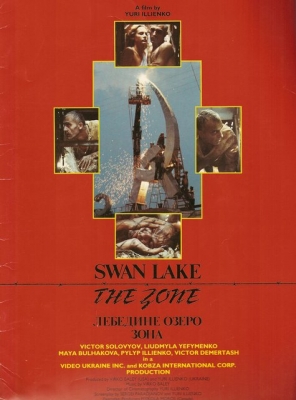

The latter text was actually transcribed by Ilyenko from recordings of a 1988 conversation with Paradjanov. It resulted in the second and last major Paradjanov-Ilyenko collaboration: 1989’s astonishing SWAN LAKE: THE ZONE/LEBEDYNE OZERO. ZONA. It’s a film that doesn’t really resemble either man’s work, being much closer to the work of Tarkovsky or Alexander Sokurov in its brooding atmosphere and glacial pacing.

Taking place in a bleak industrial landscape in the calamitous final days of the Soviet Union, it opens with an escaped prisoner (Viktor Solovyov) hiding out inside a hollow hammer-and-sickle monument (the first example of the film’s sledgehammer symbolism, and by no means the last). He’s visited by a mischievous kid (Ilyenko’s son Pylyp) and the latter’s love-starved mother (Ilyenko’s second wife Lyudmila Efimenko), with whom he has sex. Eventually the prisoner is captured by authorities and taken back to the prison camp from which he escaped, but not until after he’s been brought back from the dead by a blood transfusion (complete with Biblical voice-overs—more none-too-subtle symbolism). In the end the guy commits suicide by slashing his wrists with a broken light bulb as Efimenko waits by the monument, eager for his return.

There’s very little dialogue in this hallucinatory film, which relies entirely on Ilyenko’s wizardly visual sense (as usual, he acted as his own cinematographer), not to mention a strikingly textured soundtrack. Many Paradjanov fans have complained that the film is grim and upsetting in a very un-Paradjanov manner, but his scenario was in fact even grimmer than the finished film (with a much greater concentration on the callousness of the protagonist’s fellow prisoners). No, SWAN LAKE: THE ZONE doesn’t approach the brilliance of SHADOWS OF FORGOTTEN ANCESTORS, but it does add up to a strange and fascinating piece of impressionistic delirium.

Paradjanov died in July 1990, but lived to see the finished cut of SWAN LAKE: THE ZONE. This is evident in PARADJANOV: SCORE OF CHRIST IN C MAJOR/PARADZHANOV. PARTYTURA KHRYSTA DO MAZHOR (1994), a 24 minute camcorder documentary by Ilyenko. Taking place on September 21, 1989 (we know this because the date appears in the lower right corner of the screen), it consists of a lengthy conversation between these two old friends inside Paradjanov’s gaudily decorated house, which is so jam-packed with objects d’art and assorted junk that Ilyenko has a hard time taking it all in—although he makes a valiant effort, engaging in a jittery visual study of the walls and shelves while the cancer ridden but still irrepressible Paradjanov chatters on.

The occasion for this meeting was the completion of SWAN LAKE: THE ZONE, which Ilyenko was anxious to screen for Paradjanov, and also the resignation of the high ranking Communist official Vladimir Vasilevich Shcherbitsky, who was responsible for Paradjanov’s imprisonment (and would die the following year). That resignation is indicated in a newspaper article that Paradjanov is seen gleefully reading.

PARADJANOV: SCORE OF CHRIST IN C MAJOR is a trifle in the Ilyenko cannon, but as a verite portrait of Paradjanov and his world it ranks pretty high. In fact, I’d say it’s superior to more celebrated Paradjanov docos like PARADJANOV: A REQUIEM (1994) and PARDJANOV: THE LAST COLLAGE/PARAJANOV. VERJIN KOLAZH (1995).

In the wake of Paradjanov’s demise Ilyenko continued to make films, although doing so didn’t get any easier after the dissolution of the Soviet Union. It took until 2002 for him to complete another feature, the hallucinatory historical chronicle A PRAYER FOR HETMAN MAZEPA/ MOLITVA ZA GETMANA MAZEPU. Its banning by Russia’s Ministry of Culture led to Ilyenko announcing his resignation from filmmaking, because “I don’t want to deal with this gangster government.”

That dissatisfaction may well have led to his subsequent political stance. In 2006 and ‘07 Ilyenko ran for Ukrainian parliament as part of the notorious far right outfit Svoboda, during which he warned that if current political practices ran unchecked Ukraine would “disappear without a trace in the whirlpool of Zionist globalism,” and published a book in which he further outlined his assertions. He lost (thankfully), although the sentiments Ilyenko expressed haven’t gone away.

What might Paradjanov have made of his friend’s late-in-life political awakening? More to the point, might Paradjanov have shared Ilyenko’s incendiary views? Obviously I can’t say, but will concede that it’s always a mistake to assume an artist/filmmaker is a great person based on their output (recall the critic who jackassedly gushed about Andrei Tarkovsky having “a nobility of spirit rare in contemporary art and almost without parallel in contemporary cinema,” even though all evidence suggests the man was a flaming asshole), and anyway, Paradjanov and Ilyenko always seemed to be largely in synch opinion-wise. They did make some great films, though.