Kids books, children’s literature, juvenile fiction…call them what you will, but regarding such books one thing is certain: most of them are pretty worthless. This goes doubly for child-targeted horror fiction, which tends to be synonymous with mediocrity. That’s certainly what I’ve found upon revisiting childhood favorites like THE GHOST BELONGED TO ME by Richard Peck, THE HOUSE WITH A CLOCK IN ITS WALLS by John Bellairs and the DARK FORCES series, which from an adult perspective amount to very little.

For truly potent kid lit one has to go back to the (so-called) fairy tales that underlie today’s fiction, and the world’s most famous tellers of such fare: Germany’s Jakob and Wilhelm Grimm. Nearly every great fairy tale in existence was related during the years 1812-57 by the Grimms, who have been criticized for watering down their folklore-inspired narratives for children. In their original grown-up versions those tales (as related in the recently published TURNIP PRINCESS AND OTHER NEWLY DISCOVERED FAIRY TALES by Franz Xaver von Schonwerth) tend to be quite raw, with sexual innuendoes and bloodletting a’plenty.

Yet child-centered though they may be, the Grimms’ tales are profoundly stark and nasty in their depictions of punishment and retribution. As one who grew up (as most likely did you) hearing watered-down Grimm retellings-–in which, for instance, Little Red Riding Hood’s grandmother is revealed to have been hiding in the closet during her granddaughter’s confrontation with the wolf (in the original both gals are devoured)-–it was quite a revelation to discover the Brothers Grimm in undiluted form.

An especially potent compilation of Grimm madness can be found in the Chronicle Books volume GRIMM’S GRIMMEST, which as the title promises contains 19 of the absolute grimmest Grimm tales. Included are “The Juniper Tree,” in which an evil woman decapitates her stepson and mixes his remains into a pudding she feeds her husband(!), prior to being crushed by a millstone for her crimes. “The Dog and the Sparrow” contains enough animal cruelty for an entire book in its account of the doomed friendship between a dog and a sparrow; before the tale is done the dog meets a gruesome end, as do three horses and their brutish owner. “Aschenputtel” is the story that became “Cinderella,” in which, among other horrors, the title character’s stepsisters mutilate their feet to fit into Cinderella’s (golden not glass) slipper. There’s also “The Story of the Youth who Went Forth to Learn How to Shudder,” which indeed he does, but not before said youth breaks a man’s leg, kills several wild animals, beats an old man nearly to death and gets doused with a bucketful of slimy fish.

An especially potent compilation of Grimm madness can be found in the Chronicle Books volume GRIMM’S GRIMMEST, which as the title promises contains 19 of the absolute grimmest Grimm tales. Included are “The Juniper Tree,” in which an evil woman decapitates her stepson and mixes his remains into a pudding she feeds her husband(!), prior to being crushed by a millstone for her crimes. “The Dog and the Sparrow” contains enough animal cruelty for an entire book in its account of the doomed friendship between a dog and a sparrow; before the tale is done the dog meets a gruesome end, as do three horses and their brutish owner. “Aschenputtel” is the story that became “Cinderella,” in which, among other horrors, the title character’s stepsisters mutilate their feet to fit into Cinderella’s (golden not glass) slipper. There’s also “The Story of the Youth who Went Forth to Learn How to Shudder,” which indeed he does, but not before said youth breaks a man’s leg, kills several wild animals, beats an old man nearly to death and gets doused with a bucketful of slimy fish.

Such sublime dementia is difficult to top, much less match, yet there was a Nineteenth Century German kids’ book that gave the Grimms a serious run for their money in ugliness and outrage: STRUWWELPETER by Heinrich Hoffmann. Originally published in 1845, STRUWWELPETER is a collection of rhymes describing various horrible misfortunes that befall misbehaving kids, written by a respected physician as a “gift” for his young son.

is a collection of rhymes describing various horrible misfortunes that befall misbehaving kids, written by a respected physician as a “gift” for his young son.

“The Story of Romping Polly” is about a girl who breaks a leg after disobeying her aunt’s warning to “be more steady.” “The Little Glutton” disregards her mother’s entreaty to stop overeating, and as a result is attacked by a hive-full of bees, while “Jimmy Spiderlegs” loses all his arms and legs after too many slides down a stairway banister. The set-up in all cases is the same: a misbehaving child disobeys an adult’s instructions and meets a horrific fate.

Those fates vary, of course, in severity and plausibility. Many are decidedly fantastic, and even downright surreal, such as the giant nose grafted onto the face of “Ned the Toy-Breaker,” the stretching neck of “Phoebe Ann, the Proud Girl,” and the eyeballs of “The Crybaby,” which fall out of their sockets due to excessive crying. Then there are downright horrific entries like “The Story of Little Suck-A-Thumb,” whose thumbs are sliced off by a spectral Scissor Man, and “Cruel Paul,” who gets bitten to death by a pack of wild animals.

The latter half of the nineteenth century gave us the writings of Scotland’s incomparable George MacDonald (1824-1905). MacDonald’s childrens’ tales, the finest examples of which can be found in the omnibus volume THE COMPLETE FAIRY TALES, are less violent than those of the Grimms and Hoffmann, but just as subversive. Examples include “Cross Purposes” and “The Golden Key,” which bring the hallucinatory atmosphere of MacDonald’s adult oriented “dream romances” PHANTASTES and LILITH into the more sanitized realm of children’s fiction. Few other writers then or now are as skilled at capturing the texture of dreams, and these tales are as authentically dreamlike as any you’ll read.

The latter half of the nineteenth century gave us the writings of Scotland’s incomparable George MacDonald (1824-1905). MacDonald’s childrens’ tales, the finest examples of which can be found in the omnibus volume THE COMPLETE FAIRY TALES, are less violent than those of the Grimms and Hoffmann, but just as subversive. Examples include “Cross Purposes” and “The Golden Key,” which bring the hallucinatory atmosphere of MacDonald’s adult oriented “dream romances” PHANTASTES and LILITH into the more sanitized realm of children’s fiction. Few other writers then or now are as skilled at capturing the texture of dreams, and these tales are as authentically dreamlike as any you’ll read.

This isn’t to say that MacDonald didn’t have a nasty side, as evinced by “The Giant’s Heart.” As the Grimms did in their tales, MacDonald based it on actual folklore, in this case the Norwegian fairy tale “The Giant Who Had No Heart in His Body” (found in the 1912 volume POPULAR TALES FROM THE NORSE). The man-eating giant of MacDonald’s story likewise lacks a heart in his body, and when two overly inquisitive children find themselves trapped in the giant’s lair they decide to track down the heart to subdue their foe…but not until after witnessing a fellow child get boiled alive!

Originally published in London in 1885, ANYHOW STORIES, MORAL AND OTHERWISE by Lucy Clifford remains one of the great  curiosities of the Victorian era, a children’s book of considerable richness and bizarrie–and not a little darkness. The undoubted standout is “The New Mother,” a staunchly uncompromising fable featuring two children who (in true Grimm/Hoffmann fashion) pay a heavy price for being naughty in what ultimately adds up to a rather profound depiction of loss and despair.

curiosities of the Victorian era, a children’s book of considerable richness and bizarrie–and not a little darkness. The undoubted standout is “The New Mother,” a staunchly uncompromising fable featuring two children who (in true Grimm/Hoffmann fashion) pay a heavy price for being naughty in what ultimately adds up to a rather profound depiction of loss and despair.

That sense of loss pervades most of the remainder of the stories, especially “The Imitation Fish,” about a fake fish tossed into the sea, where it’s shunned by all the real fish. There’s also “The Story of Willy and Fancy,” the book’s most overtly surreal account. It concerns a lonely boy befriended by a spectral girl who helps satisfy his desire to travel to the end of the world. Equally worthy is the verse poem “The Paper Ship,” with its eerie descriptions of lifeless dolls and stuffed animals (“And all of them stared at me/With large glass eyes that never had blinked/And never a one could see”). The stories’ spectral beauty and sheer strangeness set them far beyond most children’s literature–and for that matter most grown-up fiction.

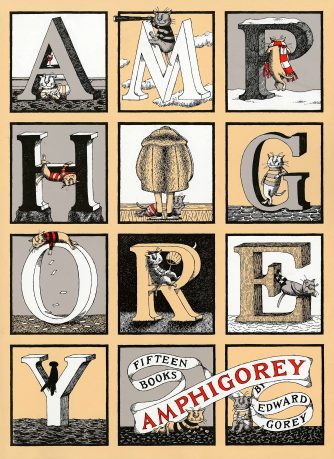

Moving into the Twentieth Century, one can discern the demented spirit of STRUWWELPETER in the macabre whimsy of Edward Gorey, whose cartoon strips contain more than a hint of the child-centered sadism of Heinrich Hoffmann. Especially representative Gorey rhymes, collected in the essential 1972 compilation AMPHIGOREY, include “An Edwardian father named Vdgeon/Whose offspring provoked him to dudgeon/Used on Saturday nights/To turn down the lights/And chase them around with a bludgeon” and “The sight of uncle gives no pleasure/But rather causes much alarm/The children know that at his leisure/He plans to have them come to harm.”

Moving into the Twentieth Century, one can discern the demented spirit of STRUWWELPETER in the macabre whimsy of Edward Gorey, whose cartoon strips contain more than a hint of the child-centered sadism of Heinrich Hoffmann. Especially representative Gorey rhymes, collected in the essential 1972 compilation AMPHIGOREY, include “An Edwardian father named Vdgeon/Whose offspring provoked him to dudgeon/Used on Saturday nights/To turn down the lights/And chase them around with a bludgeon” and “The sight of uncle gives no pleasure/But rather causes much alarm/The children know that at his leisure/He plans to have them come to harm.”

Remnants of STRUWWELPETER are also evident in the controversial kid books of Roald Dahl (1916-1990). Foremost among them is 1964’s CHARLIE AND THE CHOCOLATE FACTORY, in which bad kids are dealt some mighty harsh punishments for their wrongdoings inside the titular factory. Of a similar hue is Dahl’s oft-censored THE WITCHES, which boasts a compellingly horrific narrative about a kid staying in a hotel infested with evil witches.

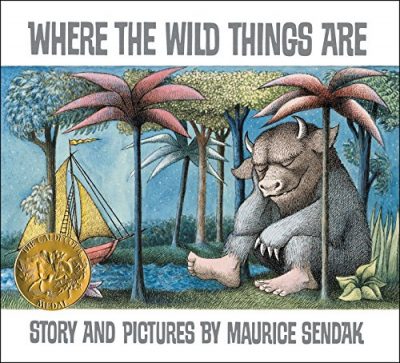

Beyond that one is left high and dry when searching for Twentieth Century kid lit that approaches the children’s fiction of old. That’s due in large part to fact that child-rearing practices of the time were far more liberal than those in vogue a century earlier. The most iconic kids’ book of our time, after all, is Maurice Sendak’s WHERE THE WILD THINGS ARE, in which a misbehaving child gives his anti-social  tendencies free reign in a wild bacchanal with otherworldly creatures in a faraway land, for which he’s ultimately rewarded in the form of the hot supper he was initially denied. Heinrich Hoffmann would be appalled!

tendencies free reign in a wild bacchanal with otherworldly creatures in a faraway land, for which he’s ultimately rewarded in the form of the hot supper he was initially denied. Heinrich Hoffmann would be appalled!

As for modern-day equivalents of the work of the Brothers Grimm, Heinrich Hoffmann, George MacDonald or Lucy Clifford, I have yet to find any. The popular A SERIES OF UNFORTUNATE EVENTS series of books (1999-2006) by Lemony Snicket, a.k.a. Daniel Handler, tend to trumpet their alleged nastiness (from the back cover of the first: “I’m sorry to say that the book you are holding in your hands is extremely unpleasant. It tells an unhappy tale…”) but are in reality high-spirited accounts of childish ingenuity. THE SAVAGE by David Almond (2008) has a truly horrific set-up involving a boy conjuring up an axe-wielding savage whose reign of terror grows all-too-real, only to squander it in a narrative that grows excessively preachy and uneventful. One can only imagine what the Brothers Grimm might have done with such material!