Russian horror cinema? Yes, there is such a thing, although examples of such tend to be few and far between. Obviously horror never jibed especially well with the tenants of the Soviet years and their strict adherence to “Soviet Realism,” and nor is it too compatible with the type of poetic reveries practiced by seminal Russian filmmakers like Alexander Dovzhenko and Andrei Tarkovsky. Nonetheless, there do exist several strong, and even essential, Russian horror films.

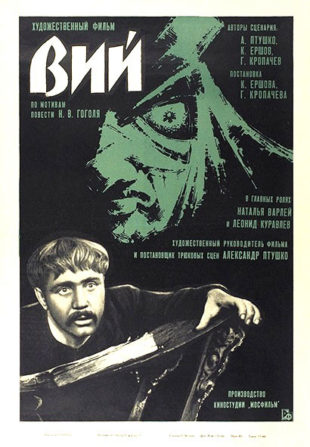

Just check out the astonishing VIY from 1967, the first and arguably best Russian horror film. Adapted from a 19th Century story by Nikolai Gogol, it’s a first-class exercise in gothic delirium that boasts a wealth of extraordinary low budget special effects.

Just check out the astonishing VIY from 1967, the first and arguably best Russian horror film. Adapted from a 19th Century story by Nikolai Gogol, it’s a first-class exercise in gothic delirium that boasts a wealth of extraordinary low budget special effects.

The amazing sights on display include the hapless protagonist flying through the air with a witch on his back, a vampire woman riding a floating coffin and the climactic procession of hell-spawned monsters, which remains a benchmark of hackle-raising horror. Credit goes to the film’s directors Georgi Kropachyov and Konstantin Yershov, whose skill with lighting and set decoration (Kropachyov is a noted production designer) is evident throughout, as well as the legendary fantasy filmmaker Alexander Ptushko (of SADKO and RUSLAN AND LUDMILA), who handled the special effects. Their combined efforts resulted in a triumph of ingenuity and imagination that has yet to be equaled, much less surpassed.

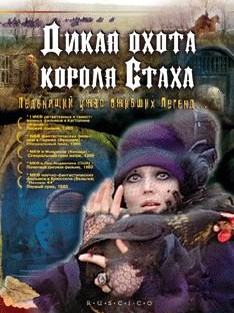

Moving forward to 1979, we come to THE SAVAGE HUNT OF KING STACH (DIKAYA OKHOTA KOROLYA STAKHA), a somewhat more traditional horror fest. Inspired by a 1964 novel by Uladzimir Karatkievic, the film is about a (seemingly) ghostly band of 17th Century hunters who are seeking to kill off the ancestors of those who betrayed and murdered their leader.

Moving forward to 1979, we come to THE SAVAGE HUNT OF KING STACH (DIKAYA OKHOTA KOROLYA STAKHA), a somewhat more traditional horror fest. Inspired by a 1964 novel by Uladzimir Karatkievic, the film is about a (seemingly) ghostly band of 17th Century hunters who are seeking to kill off the ancestors of those who betrayed and murdered their leader.

The problem with the film (and the novel) is that it explains away its tantalizingly spooky premise in a disappointing SCOOBY DOO-like coda, wherein we learn all the ghostliness has a rational explanation. Phooey! I do recommend this film, however, for its gorgeous dark-hued photography and powerfully ominous ambiance. In this respect it favorably recalls the work of masters of the form like Georges Franju and Mario Bava, and had THE SAVAGE HUNT OF KING STACH sustained that ominous air it might well have joined their company.

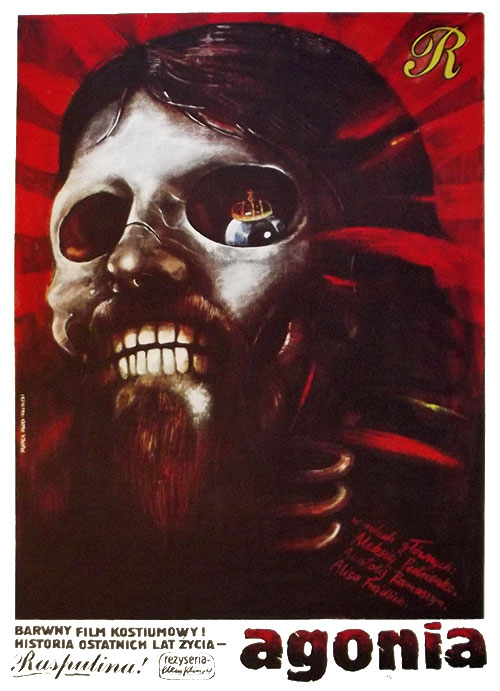

Elem Klimov’s frenzied historical epic AGONY (AGONIYA) wasn’t intended as a horror movie, yet that’s  arguably how it wound up. It’s an epic dramatization of the reign of Nikolai Rasputin, a peasant who managed to exert a near-hypnotic influence over the Russian Tsar and Tsarina during the early part of the 20th Century. There exists at least one outright horror movie on the subject, 1966’s Hammer production RASPUTIN THE MAD MONK (with a suitably over-the-top Christopher Lee in the title role), but Klimov’s is by far the most horrific and excessive Rasputin film ever made. It was completed in 1975 and promptly banned by communist authorities, only to reappear in a pared-down 143-minute cut in the eighties, which is the version currently available on DVD and the one under review here.

arguably how it wound up. It’s an epic dramatization of the reign of Nikolai Rasputin, a peasant who managed to exert a near-hypnotic influence over the Russian Tsar and Tsarina during the early part of the 20th Century. There exists at least one outright horror movie on the subject, 1966’s Hammer production RASPUTIN THE MAD MONK (with a suitably over-the-top Christopher Lee in the title role), but Klimov’s is by far the most horrific and excessive Rasputin film ever made. It was completed in 1975 and promptly banned by communist authorities, only to reappear in a pared-down 143-minute cut in the eighties, which is the version currently available on DVD and the one under review here.

You can certainly argue with this film’s Soviet-friendly portrayal of Rasputin as a blathering psychopath. Most accounts I’ve read (including Rene Fulop-Miller’s RASPUTIN THE HOLY DEVIL and a memoir by Rasputin’s daughter) depict the man as a dedicated and enormously charismatic individual who liked to party not unlike a Russian Bill Clinton), which definitely isn’t how he’s portrayed here. Yet taken purely for it is—an unabashedly nightmarish, almost CALIGULA-esque depiction of a country held captive by a madman—I can’t argue that AGONY works smashingly well, with a lead performance by Alexei Petrenko that’s so wildly unhinged it often approaches camp…and so fits right in with the film as a whole.

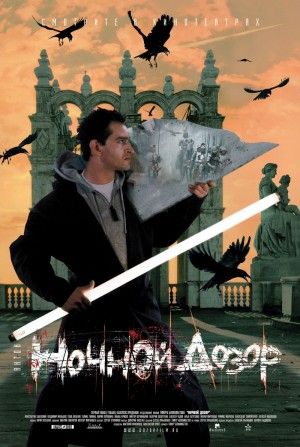

We’ll have to skip over a full two decades to arrive at the following selection. To be sure, Russia turned out many interesting horror-tinged science fiction dramas during the eighties (LETTERS FROM A DEAD MAN, KIN-DZA-DZA), and the nineties brought quite a few notable cult films (CITY ZERO, OF FREAKS AND MEN), but it wasn’t until 2004 that the next great Russian horror film arrived: Timur Bekmambetov’s NIGHT WATCH (NOCHNOY DOZOR).

We’ll have to skip over a full two decades to arrive at the following selection. To be sure, Russia turned out many interesting horror-tinged science fiction dramas during the eighties (LETTERS FROM A DEAD MAN, KIN-DZA-DZA), and the nineties brought quite a few notable cult films (CITY ZERO, OF FREAKS AND MEN), but it wasn’t until 2004 that the next great Russian horror film arrived: Timur Bekmambetov’s NIGHT WATCH (NOCHNOY DOZOR).

It’s an unabashedly flashy and commercial product about an age-old battle between supernaturally endowed good and evil factions, whose participants keep day and night watches to contain each other. The film is despised by many but I got a kick out of it, if only because it’s extremely well produced and has a wonderfully unhinged, go-for-broke spirit reminiscent of Tsui Hark’s Hong Kong classic ZU: WARRIORS FROM THE MAGIC MOUNTAIN.

Originally made for Russian television, NIGHT WATCH was an attempt at competing with Hollywood special effects extravaganzas, and, in its native country (where it quickly became a box office smash) it definitely achieved its goal. The ending, needless to add, leaves the door wide open for a sequel, which arrived in the form of ‘05’s equally bombastic DAY WATCH. A third WATCH film has been promised but has yet to materialize.

Finally we have what may be the most Russian-seeming film on this list: Alexandr Sokurov’s FAUST from  2011. A brooding, poetic and unabashedly arty reverie, the film was shot in German with continuous dialogue, much of it taken directly from Goethe’s text. Nonetheless, the film is pure Alexandr Sokurov through and through. Sokurov was a protégée of the late Andrei Tarkovsky, and has taken his mentor’s place as Russia’s premiere art-house filmmaker with highly idiosyncratic films like MOTHER AND SON (1997) and RUSSIAN ARK (2002). FAUST, despite its surfeit of dialogue (Sokurov’s other films have been called “filmed paintings”), is very much a like-minded addition.

2011. A brooding, poetic and unabashedly arty reverie, the film was shot in German with continuous dialogue, much of it taken directly from Goethe’s text. Nonetheless, the film is pure Alexandr Sokurov through and through. Sokurov was a protégée of the late Andrei Tarkovsky, and has taken his mentor’s place as Russia’s premiere art-house filmmaker with highly idiosyncratic films like MOTHER AND SON (1997) and RUSSIAN ARK (2002). FAUST, despite its surfeit of dialogue (Sokurov’s other films have been called “filmed paintings”), is very much a like-minded addition.

The film is not for everybody, having apparently inspired mass walkouts during preliminary screenings. Yet those willing to brave Sokurov’s labyrinths and enigmas are in for a difficult yet rewarding viewing experience that’s about as close to a dream as cinema has come. I will concede, however, that Sokurov’s film is a lot more fun to describe and/or think back on than it is to sit through.