For those of us who came of age in the 1980s, the name Joel Schumacher, a film director who died on June 22 at age 80, has great meaning. Even if it doesn’t you’re probably familiar with at least a portion of his filmography. His movies weren’t always “good,” but that, frankly, is beside the point, as Schumacher’s brand of moviemaking was never intended to produce great art—and anyway, a number of his movies (yes, they are most definitely movies and not “films”) are indeed pretty damn good.

For those of us who came of age in the 1980s, the name Joel Schumacher, a film director who died on June 22 at age 80, has great meaning. Even if it doesn’t you’re probably familiar with at least a portion of his filmography. His movies weren’t always “good,” but that, frankly, is beside the point, as Schumacher’s brand of moviemaking was never intended to produce great art—and anyway, a number of his movies (yes, they are most definitely movies and not “films”) are indeed pretty damn good.

Not all of Schumacher’s movies were financially successful, but they tended to showcase an unparalleled ability to capture the zeitgeist. That Schumacher began his career as a fashion designer in the 1960s, and continued as a movie costumer in the 70s, explains the obsession his self-directed movies had with trendy hairstyles, wardrobes and flashy visuals.

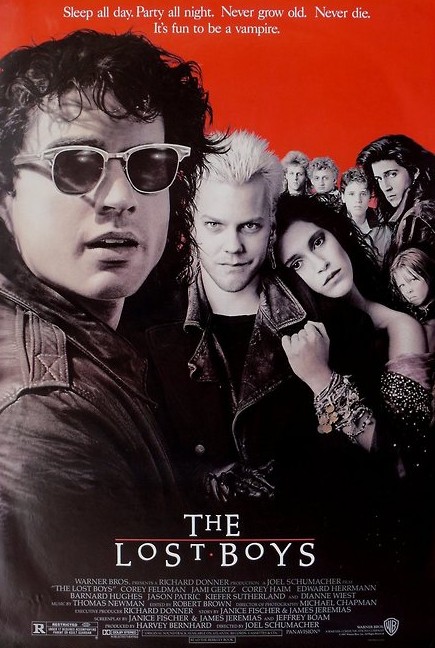

It was Schumacher who, after John Hughes, is most widely credited with establishing the “brat pack” contingent of 1980s-era actors that included Emilio Estevez, Rob Lowe, Judd Nelson, Andrew McCarthy, Ally Sheedy and Demi Moore. As if that weren’t enough, Schumacher was also the creator of the entity known as “the Coreys,” consisting of the late Corey Haim and Corey Feldman (who were first paired onscreen in Schumacher’s THE LOST BOYS), about which he later admitted “I’m not sure that was the greatest thing.”

That his name has become synonymous with “eighties hack” seems a bit unfair, as he did have a vision, although it does bespeak how ubiquitous Schumacher’s films have become. You don’t hear less-known names like Alan Metter, Jeff Kanew or David Greenwalt being equated with eighties-era cinematic hackwork, even though any of them would have fit the term better than Joel  Schumacher.

Schumacher.

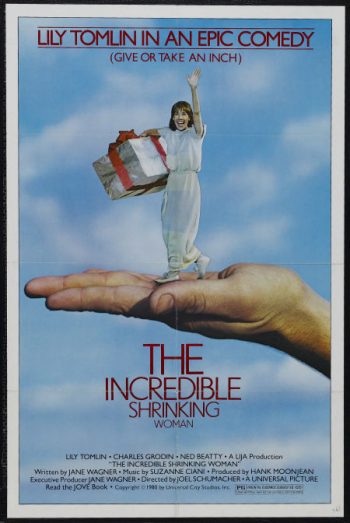

I’ll always remember his debut feature THE INCREDIBLE SHRINKING WOMAN from its near-constant rotation on cable television. It’s far from great, but adequately showcased Schumacher’s talent for crafting inoffensive and enjoyable cinema. Film scholars might not be too jazzed by such fare, but there is a place for it in the heart (and streaming platform) of every film buff, whether they admit to it or not.

Schumacher’s second movie, the urban comedy D.C. CAB (1983), was likewise a cable TV mainstay, as was his third, the vomitous brat pack whine-fest ST. ELMO’S FIRE (suggesting that Schumacher, like quite a few other eighties moviemakers, owes a sizeable debt to HBO). The vampire themed horror-comedy THE LOST BOYS followed, and marked Schumacher’s signature style: an ultra-flashy, kinetic visual extravaganza whose glitz is strictly surface-level, lacking any real innovation or artistry. A quintessentially 1980s style, in other words, which made Schumacher an ideal director for that decade.

It was in the eighties, remember, that more artistically motivated filmmakers like Martin Scorsese and Robert Altman were forced to abandon, or at least tame, their idiosyncrasies. The eighties saw Scorsese forced to take on commercial assignments (like AFTER HOURS and THE COLOR OF MONEY) and Altman relegated to made-for-TV movies and no-budget theatrical adaptations (SECRET HONOR, BEYOND THERAPY, etc.) while Schumacher thrived.

Schumacher’s major competition? It included the talented but irascible Herbert Ross, a former choreographer and 1970s holdover who after flopping with his 1981 passion project PENNIES FROM HEAVEN found himself stuck helming a rapidly diminishing succession of commercial crap; Michael Schultz, who directed Schumacher’s script for CAR WASH back in 1976, and probably would have done a better job than Schumacher did with D.C. CAB, which was essentially CAR WASH 2 (instead Schultz made 1985’s KRUSH GROOVE, a sanitized depiction of the founding of Def Jam Recordings); Martha Coolidge, who specialized in turning trashy teen comedies into semi-respectable mainstream fare like 1983’s VALLEY GIRL and ‘85’s REAL GENIUS (and who twice got fired for tweaking the scripts she was tasked with filming); Adrian Lyne, whose 1983 FLASHDANCE (the title, that is) could well sum up Schumacher’s career; James Bridges, another seventies holdover who directed 1988’s BRIGHT LIGHTS, BIG CITY, a film initially intended for Schumacher; and the late Tony Scott, who often came off like a more macho variant on the famously gay Schumacher.

Schumacher’s major competition? It included the talented but irascible Herbert Ross, a former choreographer and 1970s holdover who after flopping with his 1981 passion project PENNIES FROM HEAVEN found himself stuck helming a rapidly diminishing succession of commercial crap; Michael Schultz, who directed Schumacher’s script for CAR WASH back in 1976, and probably would have done a better job than Schumacher did with D.C. CAB, which was essentially CAR WASH 2 (instead Schultz made 1985’s KRUSH GROOVE, a sanitized depiction of the founding of Def Jam Recordings); Martha Coolidge, who specialized in turning trashy teen comedies into semi-respectable mainstream fare like 1983’s VALLEY GIRL and ‘85’s REAL GENIUS (and who twice got fired for tweaking the scripts she was tasked with filming); Adrian Lyne, whose 1983 FLASHDANCE (the title, that is) could well sum up Schumacher’s career; James Bridges, another seventies holdover who directed 1988’s BRIGHT LIGHTS, BIG CITY, a film initially intended for Schumacher; and the late Tony Scott, who often came off like a more macho variant on the famously gay Schumacher.

What gave Schumacher an edge over his fellows was his versatility. A true journeyman director, he spread his talents over numerous genres, which helped him move past the many flops he turned out. After, for instance, D.C. CAB underperformed Schumacher appears to have been forgiven, with the proviso that urban comedies simply weren’t his forte—and indeed, he never directed another. Likewise DYING YOUNG, a turgid Julia Roberts-headlined drama that tanked upon its release in 1991, ensuring that Schumacher never made another such film.

Contrast that with the case of Albert Magnoli, who after directing the hit Prince vehicle PURPLE RAIN in 1984 struck out two years  later with AMERICAN ANTHEM. Like the former film, AMERICAN ANTHEM was a flashy music driven spectacle with a famous figure whose name had been made outside Hollywood (gymnast Mitch Gaylord), and its failure put an end to Magnoli’s Hollywood career, seeing as how (in Hollywood’s eyes) that was the only type of film he was capable of turning out; as of this writing his final film credit was 1997’s DARK PLANET, a far cry from PURPLE RAIN, or even AMERICAN ANTHEM.

later with AMERICAN ANTHEM. Like the former film, AMERICAN ANTHEM was a flashy music driven spectacle with a famous figure whose name had been made outside Hollywood (gymnast Mitch Gaylord), and its failure put an end to Magnoli’s Hollywood career, seeing as how (in Hollywood’s eyes) that was the only type of film he was capable of turning out; as of this writing his final film credit was 1997’s DARK PLANET, a far cry from PURPLE RAIN, or even AMERICAN ANTHEM.

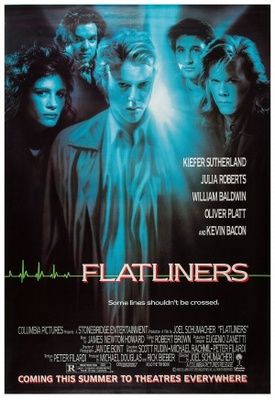

Entering the nineties it seemed that, with FLATLINERS (1990), Schumacher might have caught a second wind. It is, once again, not a great movie, but it’s also, once again, an extremely entertaining one, with Kiefer Sutherland, Julia Roberts, Kevin Bacon and others experimenting with near-death experiences. The script could have been stronger in my view, but Schumacher’s direction, for once, is the saving grace, with the emphasis on narrative momentum in a Hollywood product that actually tells a story; not a terribly good story, mind you, but one that’s related quite well.

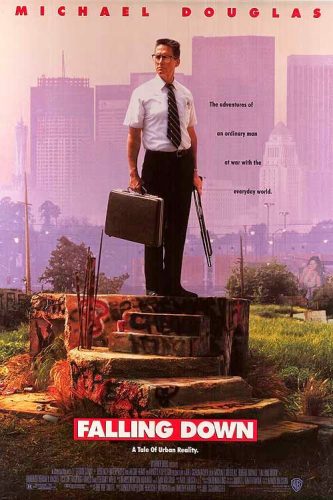

Skipping over the aforementioned DYING YOUNG, we arrive at 1993’s FALLING DOWN, arguably Schumacher’s most satisfying picture. It features Michael Douglas in what he himself has proclaimed, correctly, his greatest-ever performance as D-Fens, an LA businessman who snaps while stuck in traffic one morning (anyone who’s ever experienced an LA traffic jam can readily identify) and embarks on a rampage that takes him from downtown LA to Venice Beach, where his estranged wife (Barbara Hershey) and daughter reside. It’s a darkly funny, visually evocative and disturbing film that perfectly captured the mood in LA in the wake of the 1992 riots, while simultaneously harkening  forward to the white male rage that would become especially virulent in the coming decades.

forward to the white male rage that would become especially virulent in the coming decades.

Unfortunately FALLING DOWN, like so many Schumacher products, wasn’t perfect. It was marred by the addition of Robert Duvall as an aging inspector on D-Fens’s trail, a character and plot strand that were both hopelessly clichéd (did I mention that its Duvall’s last day?).

From there Schumacher made some puzzling choices. The first was signing onto the 1994 John Grisham adapted THE CLIENT, and the second was 1996’s A TIME TO KILL, another Grisham adaptation that provided Matthew McConoughay with his breakout role. Both were satisfying adult thrillers that actually play better today than they did previously, seeing as how grown-up dramas are currently an endangered species in Hollywood (just ask Mr. Grisham, in whose books modern moviemakers appear to have lost interest). Both movies, however, seemed somewhat removed from Schumacher’s flamboyant sensibilities.

In between them Schumacher directed 1995’s BATMAN FOREVER. It was, in contrast to Tim Burton’s dark and scary BATMAN (1989) and BATMAN RETURNS (1992), a bright, campy and unerringly family friendly entertainment. It’s well known that Warner Bros. execs were none too happy with the bleak gist of BATMAN RETURNS, and BATMAN FOREVER had a very corporate (and merchandising) friendly vibe. About the best I can say for the pic is that it’s about on par with Burton’s efforts, which are, for the record, impressively visualized but underwhelming in most all other departments. What’s surprising about BATMAN FOREVER is how far it departs from its director’s career-long predilections—as author James King wrote of Schumacher, “Kids’ films weren’t his thing.”

It was followed, unfortunately enough, by the even more kid-oriented BATMAN AND ROBIN (1997), which enraged comic geeks everywhere and tarnished Schumacher’s reputation irreparably. No wonder he spent much of the ensuing two decades apologizing for it.

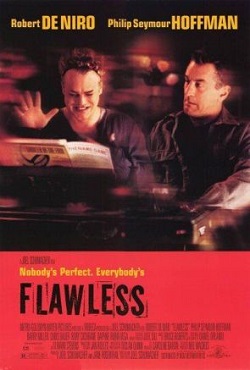

1999’s Nicolas Cage vehicle 8MM certainly did nothing to improve matters, being a thoroughly misguided filming of what was said to be a pretty powerful script by SEVEN’S Kevin Andrew Walker. The same year’s Robert de Niro-Philip Seymour Hoffman comedy FLAWLESS, by contrast, wasn’t bad, being a funny and endearing piece of work with an excellent Robert de Niro performance as a homophobic cop, matched quite nicely by the late Philip Seymour Hoffman as a drag queen with whom de Niro, after suffering a stroke, is forced to take singing lessons to help with his slurred speech.

And Schumacher continued to (mostly) thrive in the 2000s. Ever the trend-meister, he commenced the decade by joining the American independent film movement. Obviously that movement was no longer what it was back in the early nineties, when iconic films like SEX, LIES AND VIDEOTAPE, SLACKER and RESERVOIR DOGS were among the entries; in 2000, by contrast, the major indie releases were JESUS’ SON, PIECES OF APRIL and CHUCK AND BUCK, which weren’t exactly in the same league. Schumacher’s TIGERLAND, a so-so COOL HAND LUKE wannabe marked by highly mobile digital camerawork and a debuting Colin Farrell, actually fits in quite well with those post-nineties indies (which explains in part why the movement only lasted a few more years).

Colin Farrell reteamed with Schumacher in 2002’s PHONE BOOTH. It’s a cannily made suspense thriller notable for the fact that its Larry Cohen penned script took place almost entirely inside a big city phone booth, where Farrell’s character is held hostage by a sniper whose voice (spoken by Schumacher regular Kiefer Sutherland) issues from the phone.

Colin Farrell reteamed with Schumacher in 2002’s PHONE BOOTH. It’s a cannily made suspense thriller notable for the fact that its Larry Cohen penned script took place almost entirely inside a big city phone booth, where Farrell’s character is held hostage by a sniper whose voice (spoken by Schumacher regular Kiefer Sutherland) issues from the phone.

Yet for all his dabbling in independent film, Schumacher was careful to keep his feet in the big budget world. See the Schumacher directed Jerry Bruckheimer productions BAD COMPANY (2002) and VERONICA GUERIN (2003), the first a mindless action-comedy and the second a rather listless biopic about the martyred Irish crime reporter Veronica Guerin (played by Cate Blanchett). Then there was THE PHANTOM OF THE OPERA (2004), a glossy but empty-headed Andrew Lloyd Webber adaptation; Lloyd Webber invested a great deal of his own money in the film, and reportedly took a huge loss when it tanked. Not that he has anyone to blame but himself, as it was Lloyd Webber who chose Schumacher to direct the film back in the early 1990s (a decision based, allegedly, on Schumacher’s work on THE LOST BOYS).

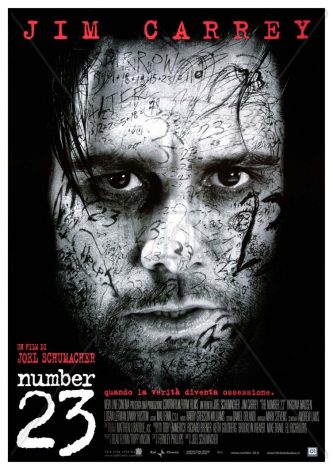

In the years after PHANTOM Schumacher kept active, but his films just weren’t what they once were. THE NUMBER 23 (2007) was a thriller that saw Jim Carrey attempting to broaden his range as an actor, playing a dog catcher who becomes obsessed with the number 23 while reading a mysterious novel. The film, like 8MM, suffers from a misguided treatment whose stylistic poles—the music video-esque dramatizations of passages from the book and the drabness of Carey’s “reality”—repeatedly clash.

As it turned out, THE NUMBER 23 was to be Schumacher’s last major film. He finished out his career with the 2009 horror film  BLOOD CREEK, a German co-production whose release was extremely limited; TWELVE, an account of wealthy teenaged drug pushers that plays like a subpar LESS THAN ZERO; and TRESPASS, a home invasion thriller with Nicolas Cage and Nicole Kidman that offers some mild B-movie thrills.

BLOOD CREEK, a German co-production whose release was extremely limited; TWELVE, an account of wealthy teenaged drug pushers that plays like a subpar LESS THAN ZERO; and TRESPASS, a home invasion thriller with Nicolas Cage and Nicole Kidman that offers some mild B-movie thrills.

Perhaps when discussing Schumacher it’s more pertinent to talk about this life than his movies. It’s not insignificant that most of the social media obituaries that have appeared thus far have focused more on the man himself, who it seems was an all-around great guy and tireless worker, than his filmic output.

I’ve found myself revisiting an August, 2019 Vulture.com interview with Schumacher, in which his life was widely discussed (and quoted). Among the interesting tidbits were a clarification of Schumacher’s feelings about Val Kilmer (“I didn’t say Val was difficult to work with on BATMAN FOREVER. I said he was psychotic”), revelations about his childhood (“I was on my own. The street was my education”), his activities in the 1960s (“I was so stoned all the time on speed, I’m lucky to be here”), his number of sexual partners (“in the double-digit thousands”) and his own filmmaking talent (“It’s very hard to realize you have a calling and realize you’re not gifted”). We also hear from Schumacher’s longtime friend Bill Maher, who claims “The reason I love Joel Schumacher is he went to a party when he was 11 and got home when he was 52.”

So perhaps it’s not a Joel Schumacher obituary we need, but a biography. Until one of those turns up we’ve got the many films he directed to keep us sated, for better or worse.