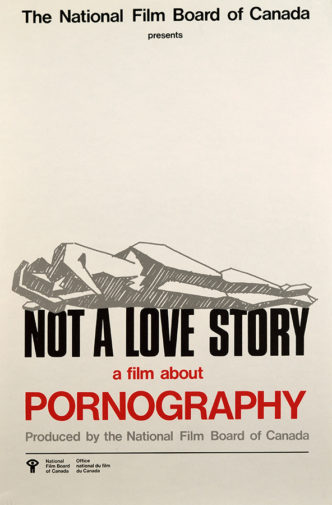

Here I’m going look to the Great White North, the source of 1981’s NOT A LOVE STORY: A FILM ABOUT PORNOGRAPHY, one of the most infamous documentaries of its time, and 1984’s THE MASCULINE MYSTIQUE, which is considerably less well known (although it did spawn two sequels, 90 DAYS and THE LAST STRAW, which I’ll also briefly discuss). The two films were made by Canada’s National Film Board, and have a definite connection, one being a feminist anti-porn screed and the other a study of male intimacy that was made in direct response to the former film.

NOT A LOVE STORY was a product of the late Studio D, the NFB’s “women’s unit.” Studio D was once described as “an island within an island within an island within an island,” and that insularity would appear to have been a prime reason for its 1996 dissolution, and the wrong-headedness of NOT A LOVE STORY. Then again, though, it’s that very wrong-headedness—i.e. an air of inflated self-righteousness that borders on psychotic—that makes the film fascinating, despite the fact that it is, frankly, a train wreck.

NOT A LOVE STORY was a product of the late Studio D, the NFB’s “women’s unit.” Studio D was once described as “an island within an island within an island within an island,” and that insularity would appear to have been a prime reason for its 1996 dissolution, and the wrong-headedness of NOT A LOVE STORY. Then again, though, it’s that very wrong-headedness—i.e. an air of inflated self-righteousness that borders on psychotic—that makes the film fascinating, despite the fact that it is, frankly, a train wreck.

The director, narrator and primary subject of NOT A LOVE STORY is Bonnie Sherr Klein, who comes off as essentially a female Travis Bickle in her single-minded crusade against pornography (a connection bolstered by footage of an NYC street drummer who also appears in TAXI DRIVER). Alternately mousey and hectoring, Klein films herself visiting a number of big city porn venues and interviewing/lecturing various people involved in the pornographic industry, together with Lindalee Tracey (1957-2006), an exotic dancer who assumes the Jodie Foster role of a corrupted angel who needs saving.

Tracey often does Klein’s work for her, as in a scene in which she berates the sleazy proprietor of a peep show for his exploitative treatment of women. Klein shows her gratitude in the next scene, by cornering Tracey outside said peep show, claiming her exotic dance routines are no different from the amoral practices of the guy she just shamed (Klein seems to lump stripping, prostitution and pornography into a single category). Throughout, endless movie clips and pornographic images are shown, all of them depicting women gagged, tied up and beaten, to demonstrate Klein’s thesis that all pornography is demeaning to women, with no opposing viewpoints offered.

Offsetting all the grossness and sleaze are interviews with the anti-porn feminists Susan Griffin, Kate Millet, Robin Morgan and Kathleen Barry, priv ileged white women all who intellectualize at length about the evils of pornography amid comfortable middle-class settings (in scenes the film’s editor Anne Henderson claims “bored me to tears”). We also see a demonstration by a boisterous group called Women Against Violence in Pornography and Media outside a San Francisco porn emporium, while enlightened manhood is represented by an uber-dweeby group of guys who call themselves Men Against Male Violence.

ileged white women all who intellectualize at length about the evils of pornography amid comfortable middle-class settings (in scenes the film’s editor Anne Henderson claims “bored me to tears”). We also see a demonstration by a boisterous group called Women Against Violence in Pornography and Media outside a San Francisco porn emporium, while enlightened manhood is represented by an uber-dweeby group of guys who call themselves Men Against Male Violence.

Klein alerts us how to feel through close-ups of her reacting to her subjects; to the feminist activists she smiles and listens intently, while the pornographers and their subjects get disapproving frowns. The film concludes with Tracey undergoing a degrading photo shoot for Hustler magazine and then reciting an essay about the demeaning effects of the preceding sequence (which apparently went a lot  further in its initial form but ended up truncated due to a technical glitch) while an approving Klein looks on, leading to a final freeze-frame of Tracey joyously dancing on a beach, apparently free of the shackles of pornography.

further in its initial form but ended up truncated due to a technical glitch) while an approving Klein looks on, leading to a final freeze-frame of Tracey joyously dancing on a beach, apparently free of the shackles of pornography.

The film’s reception was as you might expect. Anti-porn feminists loved it, of course, but overall the film caused quite a bit of controversy, even among its target audience. The so-called “porn wars” between anti-pornography and pro-sex feminists were underway, and NOT A LOVE STORY got swept up in the conflict. The feminist filmmaker Lizzie Borden has stated that her 1986 comedy WORKING GIRLS, about upscale prostitutes, was made “in response” to NOT A LOVE STORY, and Lindalee Tracey herself denounced the film repeatedly in her final years, calling it a “pretentious middle-class strike against porno.”

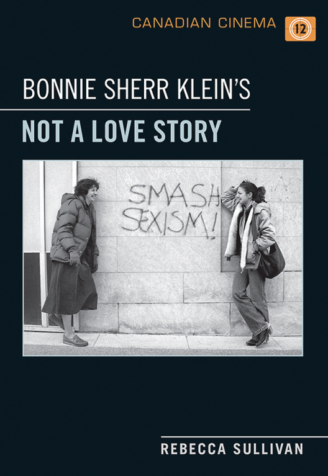

Yet the film remains famous enough that a book was written about it, BONNIE SHERR KLEIN’S NOT A LOVE STORY by Rebecca Sullivan, in 2014. In it Sullivan attempts to defend the film yet can’t keep from pointing out its “failures, flaws and lapses in judgement,” which are plentiful. In fact, I’d say the book offers a more thorough and effective takedown of NOT A LOVE STORY than many of its more vociferous detractors.

Among the things criticized are Klein’s abovementioned reaction shots, which Sullivan discredits through a quote by Janis Dale stating that “Nothing demeans a doc faster for me than employing an unauthentic voice of authority or inserting cutaways meant to tell me how to think. Klein does both.” Sullivan also finds that the film “gives too much attention to anti-porn activism,” with the feminist “experts” dismissed—correctly—as “strident,” “unconvincing,” “smug” and “condescending.” Bonnie Sherr Klein herself, in retrospective interviews for the book, is upfront about many of the film’s shortcomings, admitting that she now “cringes” at her cutaway shots and the Women Against Violence protesters, that the dudes of Men Against Male Violence “come across as wimps,” and that the concluding freeze frame “looks like an advertisement for soap.”

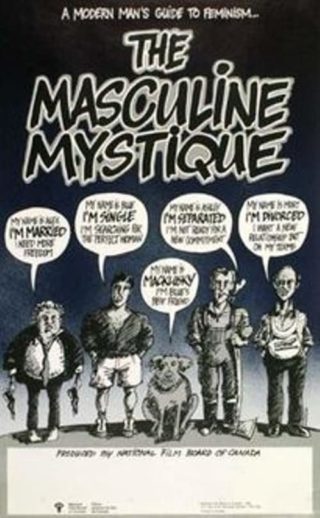

Onto THE MASCULINE MYSTIQUE. It was made by a handful of male NFB employees in reaction to the notoriety engendered by NOT A LOVE STORY and other studio D productions. As in NOT A LOVE STORY, NFB filmmakers are the main subjects of a unique gender oriented study of sexual mores, as seen from a white middle-class perspective. The similarities, however, end there, as THE MASCULINE MYSTIQUE is neither angry nor pedantic in its approach, possessing something NOT A LOVE STORY lacked: a sense of humor. Certain eighties-era critics apparently believed THE MASCULINE MYSTIQUE was a “put on,” and indeed, it’s difficult to discern how seriously we’re supposed to take scenes like the one in which one of the principal filmmakers/subjects tells his GF “You only want me for my body!”

The film, directed by John N. Smith and Giles Walker, was the first in the NFB’s “Alternative Drama” program that combined documentary and fiction. THE MASCULINE MYSTIQUE consists of four men at an informal group encounter meeting, discussing their issues with the opposite sex. The descriptions are fleshed out via staged vignettes in which the men, and their wives and children, play themselves.

The guys include Blue (Stefan Wodoslawsky), who’s attempting to keep his sexist impulses, bequeathed by his late father, at bay in his relationship with the free spirited Amurie (Char Davies). Mort (Mort Ransen) is a divorcee with three young children who desires commitment above all else, and so has a hard time with his nontraditional sexed-up GF Bet (Annebet Zwartsenberg). Alex (Sam Grana) is a selfish and short-tempered asshole who screws around on his wife and berates his children for minor offenses. Then there’s Ashley (Ashley Murray), the oldest of the group (and the one who gets the least screen time), who’s been devastated by the break-up of his marriage and is now attempting, clumsily, to raise two children on his own. At one point Alex stays overnight at Blue’s house, and the altercation that occurs the following morning shows these guys don’t understand each other any more than they do the women in their lives.

That and other scenes are funny, yet there are touching moments, such as Ashley’s heartfelt description of the effects of divorce: “Your ego is absolutely squashed to nothing, your pride in what you’ve talked about to people and what you’ve lived for and what you’ve worked for is devastated, you are just unbelievably small and you have a long, long climb back up.” The result is an occasionally pleasing but quite choppy and uneven concoction.

That and other scenes are funny, yet there are touching moments, such as Ashley’s heartfelt description of the effects of divorce: “Your ego is absolutely squashed to nothing, your pride in what you’ve talked about to people and what you’ve lived for and what you’ve worked for is devastated, you are just unbelievably small and you have a long, long climb back up.” The result is an occasionally pleasing but quite choppy and uneven concoction.

This is to say that the film’s documentary overlay is often at odds with the staged drama—the raggedy and undisciplined camerawork is always calling attention to itself, as do the sometimes-awkward performances by the non-actor cast—and the chaotic intercutting between the protagonist’s various accounts and the group encounter session prevents one from ever getting too involved in the proceedings. THE MASCULINE MYSTIQUE may not be the train wreck NOT A LOVE STORY was, but it leaves a lot to be desired.

Yet the film was, unlikely enough, a success. No books have been written about it, but THE MASCULINE MYSTIQUE accomplished something NOT A LOVE STORY didn’t: it spawned a franchise. The Giles Walker directed 90 DAYS was the 1985 follow-up, a scripted drama that follows Stefan Wodoslawsky’s Blue and Sam Grana’s Alex as the former attempts to settle down with a Korean mail order bride (Christine Pak) and the latter (who’s still a giant asshole) becomes a sperm donor. It’s a funny and perceptive little film with some terrific bits of comedy (a surprise visit by Blue’s mother and Alex’s fraught encounter with a male nurse being the stand-outs), although its screwball sequel THE LAST STRAW (1987), in which Blue discovers he’s infertile and Alex fronts a sperm donation outfit, put a none-too-auspicious end to the trilogy—or, perhaps more accurately, quartet.