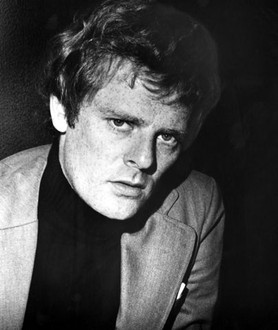

There exist three major factors that can do in a gifted filmmaker: being ahead of one’s time, having unpopular political opinions and aligning oneself with a credit-grabbing superstar. It’s a rare director who embodies all those issues, but Paul Morrissey, who died on October 28, 2024, did.

Morrissey was a true renaissance man, a fearless innovator with no ties to Hollywood. As a pioneering independent director he was as important, I’d argue, as Sam Fuller or John Cassavetes, yet is rarely (if ever) mentioned in the same breath with either. For that matter, Morrissey’s name isn’t brought up much at all these days; as the man himself lamented in 2000, “It’s like I never existed.”

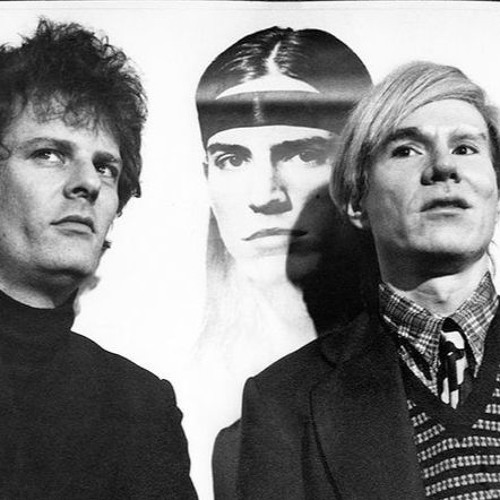

A large part of the problem was Morrissey’s decade-long association with Andy Warhol. The two connected back in 1965 because, according to Morrissey, “I was doing some little experiments at the same time Andy was doing some experiments.” Warhol’s name proved beneficial in securing financing for Morrissey opuses like HEAT (1972), FLESH FOR FRANKENSTEIN (1973) and BLOOD FOR DRACULA (1974), with the problem being that those films are more widely known as ANDY WARHOL’S HEAT, ANDY WARHOL’S FRANKENSTEIN and ANDY WARHOL’S DRACULA.

HEAT (Trailer)

As with POLTERGEIST (1982), whose director Tobe Hooper was overshadowed by producer Steven Spielberg, or the TV miniseries WILD PALMS (1993), whose creator Bruce Wagner tended to be ignored by the media in favor of executive producer Oliver Stone, it was Warhol’s name that resonated over Morrissey’s. But Hooper and Wagner each suffered credit grabbing on a single film, whereas Morrissey had his entire career overshadowed.

An interesting fact: Morrissey, despite his underground leanings, was staunchly conservative in both his politics and demeanor. He never failed to publicly reference his military background, and liked to claim his films, with their casts of whores, junkies and killers, were intended as cautionary tales. That’s an ironic stance given that the none-too-conservative Andy Warhol, his “factory” and its players—including iconic names like Nico and Joe Dallesandro—were managed by Morrissey, who furthermore had a hand in the making of 1960s era Warhol credited films like MY HUSTLER (1965) and CHELSEA GIRLS (1966). The precise nature of Morrissey’s contributions remains a point of debate, but contribute he most certainly did.

In the years following his 1975 break with Warhol, Morrissey continued making resolutely offbeat films (not counting 1978’s best-ignored HOUND OF THE BASKERVILLES, his one and only attempt at big studio filmmaking). In doing so he developed a deadpan style that foreshadowed the work of indie auteurs like Jim Jarmusch and Hal Hartley.

Morrissey was, in short, ahead of his time, which (as Francis Ford Coppola is fond of saying) is never a good thing. Being ahead of the curve was a particular problem with Morrissey grit-fests like MADAME WANG’S (1981), FORTY DEUCE (1982) and MIXED BLOOD (1984), which were widely misunderstood in their day. They actually harkened forward to the following decade, when lowlife dramas—LAWS OF GRAVITY (1992), WHERE THE DAY TAKES YOU (1992), CLOCKERS (1995), etc.—proliferated, but in the early eighties such fare felt distinctly out of place.

FORTY DUECE (Full movie)

Quality-wise Morrissey’s films ran the gamut from cloying to brilliant. In the latter category was FLESH FOR FRANKENSTEIN, in my view his best film, a still-unsurpassed mixture of art and exploitation, and its nearly-as-strong follow-up BLOOD FOR DRACULA. FORTY DEUCE and MIXED BLOOD were raggedy and unpolished, in common with their slummy settings, yet impressively stylized and memorably acted by casts that included a young Kevin Bacon and PIXOTE’s late Marília Pêra (Morrissey had very definite thoughts on acting, stating that “With a great artist you can’t tell whether they are acting or whether they are identical to the character,” and “I find the professional actors and actresses today uninteresting”).

MIXED BLOOD (Full movie)

I’ll confess I’m not hugely enamored with Morrissey’s earlier, more experimental offerings like LONESOME COWBOYS (1968), TRASH (1970) and WOMEN IN REVOLT (1971), which like BIKE BOY and CHELSEA GIRLS are easier to admire from afar than actually sit through. As for BEETHOVEN’S NEPHEW (1985) and SPIKE OF BENSONHURST (1988), which for decades seemed to be Morrissey’s final films, they simply aren’t very good, with the former a fumbled attempt at prestige filmmaking and the latter a would-be commercial comedy. (His true final film, 2010’s NEWS FROM NOWHERE, doesn’t appear to have been commercially released anywhere, and is currently MIA online.)

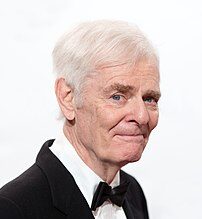

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Morrissey ended his days a bitter and lonely old man (a not-uncommon film director fate). His late-period interviews and DVD audio commentaries were invariably clogged with bitching about the sorry state of modern cinema (in which “for the past ten or so years, I don’t think anybody has done too much of anything”) and his own lack of recognition. Perhaps it would have cheered him to know that now, with Paul Morrissey no longer with us, the film world appears to have finally taken notice of this mercurial and unrestrained talent.