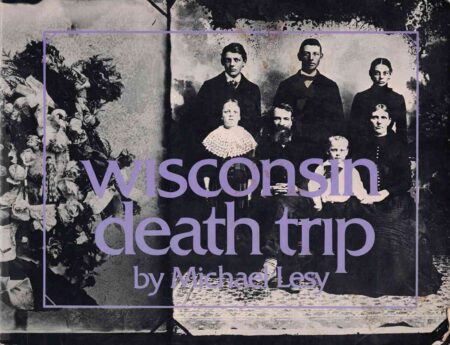

A rare (perhaps sole) example of “surreal history,” WISCONSIN DEATH TRIP is a publication whose likes you won’t see anywhere else—including the output of its own author. That author was Michael Lesy, a historian and photographer whose first book WISCONSIN DEATH TRIP was. Having begun life as a Ph.D. thesis for Rutgers University, it was published in 1973 by Pantheon Books, who provided a wholly unique layout.

A rare (perhaps sole) example of “surreal history,” WISCONSIN DEATH TRIP is a publication whose likes you won’t see anywhere else—including the output of its own author. That author was Michael Lesy, a historian and photographer whose first book WISCONSIN DEATH TRIP was. Having begun life as a Ph.D. thesis for Rutgers University, it was published in 1973 by Pantheon Books, who provided a wholly unique layout.

The subject is the Wisconsin farming town Black River Falls during 1890-1900. It was then that the community and its surrounding environs were gripped by a seeming epidemic of crime, disease and madness, exacerbated by the great depression of 1893. The book features copious vintage photographs taken by the late town photographer Charles Van Schaik (1852-1946), the negatives of which were discovered in 1970 and preserved by the Wisconsin State Historical Society. Approximately 200 of those photographs are utilized here (in the Levy’s words) “as if they were events.”

(Stephen King is evidently a fan, having used it as a direct reference for IT and the short piece, 1922.)

Lesy’s introduction to the book is oddly coy about its subject matter, if not downright vague (claiming his “primary intention is to make you experience the pages now before you as a flexible mirror that if turned one way can reflect the odor of the air that surrounded me as I wrote this”), thus reinforcing the surreal feel. The conclusion, meanwhile, is quite dated, referencing the clash between city and country life, and the “White Flight” from the big cities that occurred in the late 1960s and early 70s.

The book features copious vintage photographs taken by the late town photographer Charles Van Schaik (1852-1946), the negatives of which were discovered in 1970 and preserved by the Wisconsin State Historical Society.

Odd though it may be, WISCONSIN DEATH TRIP is quite methodically arranged. Each chapter is prefaced by a word stew indicating the subject matter to be covered (example: “Diphtheria Murder–religious Suicide Poisoning–envy Starvation Arson Grotesque insanity Brothel in the woods Amnesia and delirium Epidemic”) with the text comprised of snippets from local newspapers and books of the era, and Lesy’s own, more detailed historical reportage. The seemingly random placement of those snippets is especially important; as Lesy states, “The text was constructed as music is composed. It was meant to obey its own laws of tone, pitch, rhythm and repetition.”

Odd though it may be, WISCONSIN DEATH TRIP is quite methodically arranged. Each chapter is prefaced by a word stew indicating the subject matter to be covered (example: “Diphtheria Murder–religious Suicide Poisoning–envy Starvation Arson Grotesque insanity Brothel in the woods Amnesia and delirium Epidemic”) with the text comprised of snippets from local newspapers and books of the era, and Lesy’s own, more detailed historical reportage. The seemingly random placement of those snippets is especially important; as Lesy states, “The text was constructed as music is composed. It was meant to obey its own laws of tone, pitch, rhythm and repetition.”

“The text was constructed as music is composed. It was meant to obey its own laws of tone, pitch, rhythm and repetition.”

That text, which covers subjects like arson, insanity, murder and suicide in resolutely terse and emotionless prose, runs the gamut from perfunctory (“The reports from the burnt districts show that entire families have been destroyed”) to expansive (“A wild man is terrorizing the people north of Grantsburg…He secrets himself in the woods during the day and has the most bloodcurdling yells that have ever been heard in the neighborhood”). Cliched observations are fairly common (“Again we have been reminded of the brevity of life by the taking from among us of Mrs. F.A. Hammond”), as are questionable conclusions (“John Pabelowski, a 16 year old boy of Stevens Point, was made idiotic by the use of tobacco”).

Some portions are downright macabre, such as a report about the unearthing of a woman’s corpse, with the discovery that “The body was partly turned over and the right hand was drawn up to the face. The fingers indicated that they had been bitten by the woman on finding herself buried alive.” Others are (comparatively) mundane, as in the reports Lesy includes of repeated attempts at constructing perpetual motion machines—which inevitably drives one would-be inventor to madness. There’s even some tabloid-worthy sensationalism, as in a snippet about an invalid woman expelling a large frog after complaining of “something alive in her stomach.”

There’s even some tabloid-worthy sensationalism, as in a snippet about an invalid woman expelling a large frog after complaining of “something alive in her stomach.”

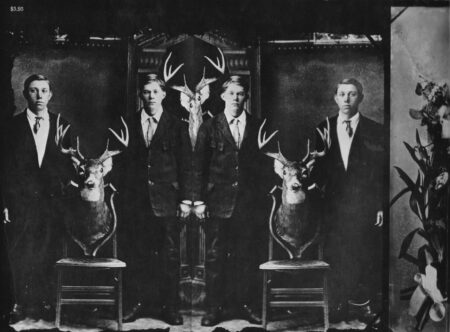

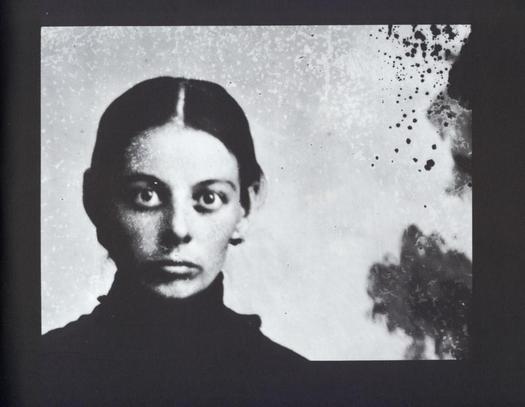

Contained between each chapter are the Van Schaik photos. Featured are nonsmiling (as was the fashion back then) family gatherings, opulently composed single person portraits, verité footage of people going about their daily business and (in another long-discarded trend) lovingly arranged depictions of deceased children in coffins. These photos are not included for mere illustrative purposes, serving a far more artistic and ephemeral role—-as is stated in the description of the subsequent Lesy tome REAL LIFE, “The text of this book is intended to elaborate not illustrate the photographs.”

Contained between each chapter are the Van Schaik photos. Featured are nonsmiling (as was the fashion back then) family gatherings, opulently composed single person portraits, verité footage of people going about their daily business and (in another long-discarded trend) lovingly arranged depictions of deceased children in coffins. These photos are not included for mere illustrative purposes, serving a far more artistic and ephemeral role—-as is stated in the description of the subsequent Lesy tome REAL LIFE, “The text of this book is intended to elaborate not illustrate the photographs.”

In yet another Lesy book, TIME FRAMES, he expounds upon his fascination with vintage photography thusly: “a photograph (is) a cultural artifact…tangled within a whole culture that was itself pinned within a social structure,” and that “to comprehend a photograph (is) like opening a set of Chinese boxes, only to discover a message that had to be translated from one language to another.” It’s that sense of foreign-ness that seems to fascinate Levy, who places special emphasis on the photos’ blurred and over-exposed portions, and often reconfigures the images into multi-picture collages, which has the paradoxical effect of bringing history to life while showing just how inscrutable the past truly is.

It’s that sense of foreign-ness that seems to fascinate Levy, who places special emphasis on the photos’ blurred and over-exposed portions, and often reconfigures the images into multi-picture collages, which has the paradoxical effect of bringing history to life while showing just how inscrutable the past truly is.

Rewards are reaped from a full engagement with the book, a superficial reading of which is more in line with what’s presented onscreen in the 1999 film adaptation of WISCONSIN DEATH TRIP. Created by the British filmmaker James Marsh (MAN ON WIRE), it consists largely of artily staged black and white recreations of several of the outrages described in the book, with narration by Ian Holm. The film (which has its admirers) may give lip service to the letter of the book, but completely misses its richness and surreality.

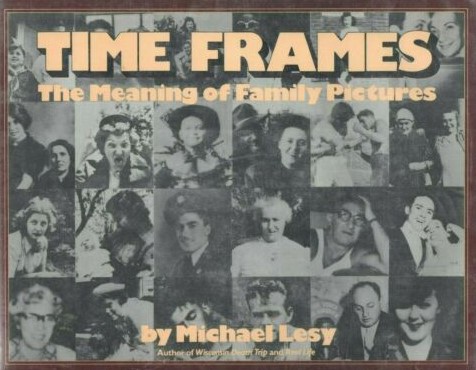

One is better off, I’d argue, checking out subsequent publications by Michael Lesy. They include REAL LIFE: LOUISVILLE IN THE TWENTIES (1976), TIME FRAMES: THE MEANING OF FAMILY PICTURES (1980) and BEARING WITNESS: A PHOTOGRAPHIC CHRONICLE OF AMERICAN LIFE, 1860-1945 (1982), all published by Pantheon. TIME FRAMES is of particular interest to readers of WISCONSIN DEATH TRIP, as it’s the closest thing that exists to a sequel.

The book consists of the confessions of several people, first and second-generation immigrants all, who lived through the era, with black and white snapshots illustrating their claims.

TIME FRAMES’ focus is on the midwestern United States in the early years of the Twentieth Century, marked by a depression whose effects outdid those of the previous one. The book consists of the confessions of several people, first and second-generation immigrants all, who lived through the era, with black and white snapshots illustrating their claims. The recountings naturally encompass great hardship, with one woman recalling the delivery of an ovarian cyst (“It had teeth. It had hair”) followed by a harrowing internment in an insane asylum, and a man describing a childhood swim in a polluted gully in which human body parts were later found.

The snapshots tend to be pretty mundane, although Lesy once again works hard to bring them to life by highlighting “accidents” in exposure and emphasizing their inherent symbolism. Images of water and trees predominate, objects that, as Lesy’s introduction makes clear, have symbolic weight that encompasses numerous cultures.

Of course neither TIME FRAMES nor any of Lesy’s subsequent publications, which include the death industry study FORBIDDEN ZONE (1987) and MURDER CITY: THE BLOODY HISTORY OF CHICAGO IN THE TWENTIES (2008), have come close to replicating the impact of WISCONSIN DEATH TRIP. It was reprinted by Anchor Books in 1991, and in 2000 by University of New Mexico Press, who gave it a cover different from that of the original Pantheon Press edition but retained the formatting.

Of course neither TIME FRAMES nor any of Lesy’s subsequent publications, which include the death industry study FORBIDDEN ZONE (1987) and MURDER CITY: THE BLOODY HISTORY OF CHICAGO IN THE TWENTIES (2008), have come close to replicating the impact of WISCONSIN DEATH TRIP. It was reprinted by Anchor Books in 1991, and in 2000 by University of New Mexico Press, who gave it a cover different from that of the original Pantheon Press edition but retained the formatting.

In terms of cultural influence WISCONSIN DEATH TRIP can be said to have adequately illustrated Lesy’s claim that, “The only reason to do art is to make more art.” Many a writer has claimed the book as an influence (Stephen King is evidently a fan, having used it as a direct reference for IT and the short piece 1922), and just as many musicians have written songs related to it (the heavy metal band Static-X put out an album called WISCONSIN DEATH TRIP). It’s even inspired filmmakers, with (the WISCONSIN DEATH TRIP film aside) the period décor of RETURN TO OZ (1985) having been reportedly copied from Charles Van Schaik’s images.

So “more art” has indeed been made from WISCONSIN DEATH TRIP. Still, to imbibe the entire macabre, provocative and surreal charge you’ll have to become acquainted with the source of it all, and return to it as often as possible.