Some filmmakers just get lucky. That’s especially true in the documentary sphere, where luck isn’t merely a virtue but, it seems, a  necessity. Up until March 2020 I believed the world’s luckiest documentary filmmaker was Andrew Jarecki, of 2003’s CAPTURING THE FRIEDMANS.

necessity. Up until March 2020 I believed the world’s luckiest documentary filmmaker was Andrew Jarecki, of 2003’s CAPTURING THE FRIEDMANS.

One of the most provocative and impactful docos of the 00s, CAPTURING THE FRIEDMANS began as a modest short about birthday clowns that became something much grander when Jarecki learned of the background of one of his principals, one David Friedman—a background that involved the incarceration of David’s father and younger brother on pedophilia charges. Even more advantageously, it transpired that the Friedmans had kept extensive home video footage of the entire sordid drama as it unfolded, which would up comprising the bulk of Jarecki’s 107 minute film.

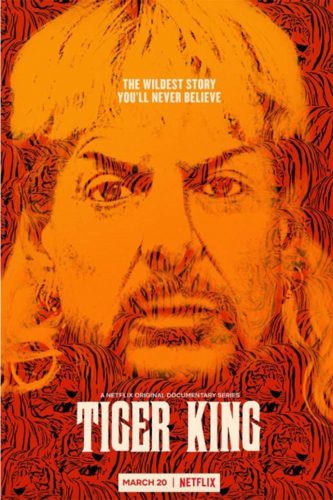

But Jarecki’s good fortune was topped on March 20, 2020, when the Netflix docu-series TIGER KING premiered. A bonafide phenomenon, TIGER KING has accrued upwards of 5 billion streaming minutes and enjoyed a 25 day ranking as Netflix’s number one show. The reasons for its popularity aren’t difficult to figure out: it’s absorbing and enjoyable, despite subject matter that at first glance doesn’t sound particularly promising. It seems the program’s co-creator Eric Goode, a passionate conservationist, forged a path directly opposite that of Jarecki, i.e. he starting with a highly expansive canvas that was gradually pared down.

that was gradually pared down.

Goode’s stated goal was to “create awareness about the suffering and exploitation of exotic animals but in a way where you can engage an audience.” His initial concept involved an exploration of various animal-centered subcultures, but he eventually narrowed his focus to concentrate on two characters: tiger breeder Joe Exotic and animal rights activist Carole Baskin. In so doing Goode uncovered a stew of madness, dismemberment, spousal abuse, embezzlement, polygamy, cults, forgery, guns, drugs, suicide, incarceration, arson and murder.

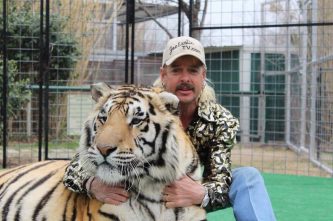

What Goode and co-creator Rebecca Chaiklin also uncovered are some amazingly varied and colorful white trash characters who make the hillbillies of DELIVERANCE look like models of refinement (for the more literarily inclined among you, the show is not unlike a Harry Crews novel come to life). Joe Exotic (real name Joseph Maldonado-Passage), the “King” of the title, is foremost among them, an insanely flamboyant, oddly charismatic gay redneck who ran an exotic animal park in Oklahoma. TIGER KING gives us an eyeful of Exotic’s questionable dealings with big cats, and also his 2019 conviction and prison sentence—Goode and Chaiklin had the good fortune of being able to profile Exotic before and after his incarceration—for the planned murder of Carole Baskin.

As presented here Baskin, the owner of the Florida based Big Cat Rescue animal sanctuary, initially seems like the saintly inverse to Joe Exotic. But, like virtually everyone in this program, she turns out to have a much darker side. The suspicious 1997 disappearance of Baskin’s husband Don Lewis is explored at some length, and Goode has strongly implied he doesn’t believe Lewis’s vanishing was entirely without premeditation on Baskin’s part (for the record, Baskin has claimed she feels “betrayed” by the series).

Other colorful individuals in TIGER KING include Bhagavan Antle, a South Carolina based wildlife park operator whose business practices and lifestyle were directly imitated by Mr. Exotic; Jeff Lowe, a Las Vegas slime ball to whom Exotic unwisely signed over his business; Joshua Dial, the hapless mastermind of Jo Exotic’s 2016 run for president of the United States(!); and Saff Saffrey, the only truly virtuous individual on display, a transgendered Iraq veteran who served as the manager of Exotic’s park (and lost an arm for his troubles).

In the documentary world such good fortune in the choice of subject matter isn’t always the case. In fact, it’s rarely the case.

“The documentary film, particularly those that seek the truth with no agenda, is an important art form that is struggling to survive in this media environment.” So claimed Joel Cheatwood, the chief content officer of the Glenn Beck owned conservative network The Blaze, on the eve of a 2012 contest dedicated to finding “The next great documentary film.” This contest was shepherded by Beck, who none-too-subtly hinted at the type of material he favored: “I’d love to see something on the Federal Reserve, the game that’s being played there. I would love to see something on why capitalism is actually a good thing.” Needless to say, this contest did not succeed in  producing the next great documentary film, but it did show just how difficult it is to come up with worthwhile nonfiction material.

producing the next great documentary film, but it did show just how difficult it is to come up with worthwhile nonfiction material.

See WELCOME TO LEITH, which documented the attempted takeover of a North Dakota town by a white supremacist, a film widely criticized for its truncated depiction. The filmmakers allegedly learned of the conflict in Leith only after it had been brewing for some time, and so missed out on some pertinent events. This, obviously, wasn’t a problem with CAPTURING THE FRIEDMANS, with its extensive home video documentation, nor TIGER KING, whose makers likewise had access to plenty of juicy pre-shot footage (such as the many outrageous YouTube videos made by Joe Exotic) in addition to having been around for a lot of pertinent events (such as Saff Saffrey’s arm ripping, which—yes—occurs on camera).

There was also the fact that in TIGER KING Goode and Chaiklin were blessed with material that was inherently unique and compelling. For an example of the inverse see KING CORN, a jazzy and energetic 2007 doco about corn growing that for all its flash can’t overcome the fact that the subject matter just isn’t very interesting. Once again: some filmmakers just get lucky—or not.

I may admittedly be wrong in bringing up KING CORN, as it, like CAPTURING THE FRIEDMANS and WELCOME TO LEITH, is a feature, whereas TIGER KING is a TV program. A docu-series to be exact, a format that encompasses the entirety of television history. Such series comprised most of the programming of British and French television in their early years, although there’s obviously a vast gap between TIGER KING and the old BBC docos, in which voice-overs filled us in on the lives of famous artists and composers (a format that lives on in the documentaries of Ken Burns), or 1960s-era French propaganda programs dedicated to glorifying the Charles De Gaulle presidency. More recent tele-docs, however, have a definite connection, particularly those made by Netflix.

The Netflix docu-series, which began in 2015 with CHEF’S TABLE, has nearly become a genre unto itself. Slick, jazzy and unerringly audience friendly, Netflix’s docos are better, for the most part, than its feature films (of which ROMA and THE IRISHMAN are outliers quality-wise rather than the norm). So too the Netflix reality TV programs, which have outdone the docu-series in popularity; it’s not insignificant that TIGER KING was knocked from its ratings perch by TOO HOT TO HANDLE, a Netflix reality series.

The Netflix docu-series, which began in 2015 with CHEF’S TABLE, has nearly become a genre unto itself. Slick, jazzy and unerringly audience friendly, Netflix’s docos are better, for the most part, than its feature films (of which ROMA and THE IRISHMAN are outliers quality-wise rather than the norm). So too the Netflix reality TV programs, which have outdone the docu-series in popularity; it’s not insignificant that TIGER KING was knocked from its ratings perch by TOO HOT TO HANDLE, a Netflix reality series.

Of course, precisely how much TIGER KING differs from the despised reality TV format is open to interpretation. “Real” documentary filmmakers would never deign to place their work anywhere near the likes of SURVIVOR or THE OSBOURNES, and TIGER KING, truth be told, isn’t that far removed from the latter. The anti-TIGER KING crowd have claimed it’s a “freakshow” and, frankly, they’re right. THE OSBOURNES, a pioneering example of reality television that delighted in exposing the weirdness and depravity of its eponymous clan, is a genuine progenitor of TIGER KING, as is THE JERRY SPRINGER SHOW, whose trailer trash guests wouldn’t be out of place amid Joe Exotic’s retinue.

Yet for all that TIGER KING is very much a Real Documentary. This is confirmed by, if nothing else, the presence of executive producer Chris Smith, a respected documentarian whose films include AMERICAN JOB (1996), AMERICAN MOVIE (1999) and COLLAPSE (2009). Smith’s output also includes the 2019 Netflix docu-series THE DISAPPEARANCE OF MADELEINE McCANN, which lasted  eight episodes (one more than TIGER KING) and failed to sustain itself.

eight episodes (one more than TIGER KING) and failed to sustain itself.

The show, about the investigation into the disappearance of a three-year-old American girl during a vacation in Portugal, probably makes for a better contrast with the subject of this essay than the aforementioned KING CORN or WELCOME TO LEITH, as it paradoxically points up one of TIGER KING’S main strengths: the way it manages to maintain audience interest throughout what initially (to these eyes, at least) seemed a needlessly inflated 5 hours. Indeed, it’s downright uncanny how Goode and Chaiklin succeed in packing so much drama into their eight episodes, each of which contains enough material to pack a more conventional documentary feature.

In speaking of drama we happen upon a major criticism of TIGER KING: its somewhat fluid relationship with “truth.” Obviously not all the drama it contains is real, which moves it further into the realm of reality TV—which would be better termed “reality” TV.

Speaking as one who gave up on SURVIVOR halfway through its third season (when it became apparent a formula had been established that its carefully chosen participants were being encouraged and/or manipulated to follow), I recognize the pratfalls, and dangers, of television’s stretching of reality. In the words of documentary producer Glen Zipper, “If we’re delivering something to you that is factually inaccurate—particularly when it has to do with something that is critically important—that ultimately could be quite dangerous” (the fact that a reality TV star was elected to run the free world handily illustrates his point).

So yes, the reality-unreality dichotomy certainly has its cons, but also some definite pros. It’s a fact that some of the finest documentaries ever made have blended fact and fiction. I’d point to Robert Kramer and John Douglas’s brilliant MILESTONES (1975), an exploration of the remnants of the 1960s counterculture that freely intermixed reality with staged drama to the point that it became impossible to discern where one began and the other left off. Likewise the documentaries of Werner Herzog, particularly LITTLE DIETER NEEDS TO FLY (1997), consisting of the late ‘Nam vet Dieter Dengler reminiscing about his experiences as a prisoner of war, and JAG MADIR (1991), about a surreal procession of eccentric performers drawn from throughout India. The former film includes details of its subject’s current existence (such as his compulsive hoarding of foodstuffs out of fear that his life might be uprooted) that Herzog admittedly fabricated, while the latter contains an extensive backstory about palaces sinking into the sea that was likewise invented by Herzog. Truth may indeed be stranger than fiction, but, as critic Clive Barnes once stated, it will never be more dramatic (I admire Frederick Wiseman’s Vietnam-era boot camp expose BASIC TRAINING, but much prefer the opening 45 minutes of FULL METAL JACKET).

So yes, the reality-unreality dichotomy certainly has its cons, but also some definite pros. It’s a fact that some of the finest documentaries ever made have blended fact and fiction. I’d point to Robert Kramer and John Douglas’s brilliant MILESTONES (1975), an exploration of the remnants of the 1960s counterculture that freely intermixed reality with staged drama to the point that it became impossible to discern where one began and the other left off. Likewise the documentaries of Werner Herzog, particularly LITTLE DIETER NEEDS TO FLY (1997), consisting of the late ‘Nam vet Dieter Dengler reminiscing about his experiences as a prisoner of war, and JAG MADIR (1991), about a surreal procession of eccentric performers drawn from throughout India. The former film includes details of its subject’s current existence (such as his compulsive hoarding of foodstuffs out of fear that his life might be uprooted) that Herzog admittedly fabricated, while the latter contains an extensive backstory about palaces sinking into the sea that was likewise invented by Herzog. Truth may indeed be stranger than fiction, but, as critic Clive Barnes once stated, it will never be more dramatic (I admire Frederick Wiseman’s Vietnam-era boot camp expose BASIC TRAINING, but much prefer the opening 45 minutes of FULL METAL JACKET).

TIGER KING might not belong in the same category as MILESTONES and LITTLE DIETER NEEDS TO FLY, but like them it amply demonstrates how a film can be enhanced by spicing its reality with scripted drama—or vice-versa. An example of the latter is a 1981 release that’s been widely linked with TIGER KING: ROAR, allegedly the “most dangerous movie ever made.”

ROAR, in contrast to the abovementioned Kramer and Herzog films, was a scripted drama enervated by unscripted reality. Set in an  African animal preserve and starring the film’s producers Tippi Hedren and Noel Marshall (the latter of whom also co-scripted and directed), the film was conceived as a comedy about the joys of animal conservation but wound up a quasi-horror movie when its cast of untrained lions and tigers acted according to their nature, and left quite a few cast and crew members (including Marshall, Hedren and daughter Melanie Griffith) with severe injuries. Not unlike TIGER KING, although in that case the predator-prey dynamic was reversed.

African animal preserve and starring the film’s producers Tippi Hedren and Noel Marshall (the latter of whom also co-scripted and directed), the film was conceived as a comedy about the joys of animal conservation but wound up a quasi-horror movie when its cast of untrained lions and tigers acted according to their nature, and left quite a few cast and crew members (including Marshall, Hedren and daughter Melanie Griffith) with severe injuries. Not unlike TIGER KING, although in that case the predator-prey dynamic was reversed.

Which brings us to the final and perhaps most grievous complaint about TIGER KING: the very real animal abuse it contains and its makers’ reaction to it. Certainly it will never be confused with good-for-you conservationist-minded docos like ANIMALS ARE BEAUTIFUL PEOPLE (1974) or BLACKFISH (2013), with TIGER KING’S “soap opera-esque drama” (as one critic termed it) often overwhelming the filmmakers’ message. But that message, I’d argue, DOES register quite strongly.

TIGER KING is quite frank in its presentation of the cruelty and neglect with which Joe Exotic treats the animals in his care. That extends to Exotic’s admitted practice of killing his tigers when they become too old and/or dangerous, a major component of his prison sentence (as is pointed out in the program, Exotic living out the remainder of his days caged is a most appropriate fate). There’s also the fact that in a show filled with jaw-dropping moments the most shocking (to me) came in the end credits, which inform us that there are currently more tigers living in captivity in the US than there are running free in the rest of the world.

The massive success of TIGER KING obviously has quite a few components. It may not entirely fulfill all of its makers’ stated goals, but succeeds as gloriously disreputable, absorbing entertainment, and a stroke of luck on the part of its makers that will probably never be replicated, much less outdone.