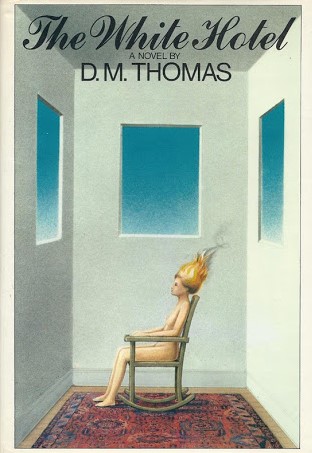

THE WHITE HOTEL, a novel written by onetime science fiction scribe turned literary darling D.M. Thomas, was initially published in 1981. The most famous of Thomas’ many works of fiction (which include BIRTHSTONE, FLYING IN TO LOVE and MEMORIES AND HALLUCINATIONS), it was an immediate publishing sensation, more so in the US (surprisingly enough) than in the author’s native Britain. The primary reason for that, according to the book’s editor Amanda Bale, was the cover art depicting a flame headed nude woman in a rocking chair, courtesy of the great Fred Marcellino (1939-2001).

THE WHITE HOTEL, a novel written by onetime science fiction scribe turned literary darling D.M. Thomas, was initially published in 1981. The most famous of Thomas’ many works of fiction (which include BIRTHSTONE, FLYING IN TO LOVE and MEMORIES AND HALLUCINATIONS), it was an immediate publishing sensation, more so in the US (surprisingly enough) than in the author’s native Britain. The primary reason for that, according to the book’s editor Amanda Bale, was the cover art depicting a flame headed nude woman in a rocking chair, courtesy of the great Fred Marcellino (1939-2001).

Of course THE WHITE HOTEL’S success is also directly attributable to its content. The novel was and remains unprecedented in its stylistic range and varying levels of reality, being one of the few examples of literary fiction that can truly be said to have just about everything: sex, violence, psychiatry, hallucination, clairvoyance and the Holocaust. There’s even a happy ending of sorts.

The idea of a happy ending, coupled with a plethora of fantastic content, in a Holocaust-tinged story might admittedly seem ill-advised. The Holocaust is always a dicey fictional proposition (Clive Barker once stated he’d never breach the subject in his writing, finding it in “bad taste”), as evinced by the novels that have attempted, directly or indirectly, to emulate THE WHITE HOTEL—including TOURS OF THE BLACK CLOCK and Thomas’s own PICTURES AT AN EXHIBITION—but failed to capture its elusive magic.

The novel begins with a lengthy poem describing an erotically charged sojourn in a secluded white hotel, marred by horrific calamities that leave masses of corpses in their wake. This poem is followed by a prose rendering of same, which is succeeded by an analysis of what we’ve just read by Sigmund Freud, drafted in a convincing imitation of Freud’s actual case histories (which Thomas calls “masterly works of literature, apart from everything else”). Here we learn these fantasies are subconscious projections of Lisa, a Ukrainian born, Vienna based opera diva who suffers from odd physical ailments caused, Freud deduces, by her own repressed desires and horrific memories of the death of her mother in a fire, mixed with premonitions—she, it transpires, is a clairvoyant who can foresee future events (although Thomas admittedly never fleshes out that aspect of the story in too satisfying a manner).

Those premonitions are born out in the later chapters, in which Lisa moves to Kiev. There she and her stepson Kolya are rounded  up by the occupying Nazis, and thrust into the 1941 massacre at Babi Yar. This section, the book’s most “terribly severe” (as claimed in a back cover blurb by Holocaust scholar Terrence des Pres), was admittedly inspired by BABI YAR, Anatoly Kuznetsov’s quasi-fictional rendering of the massacre, which has led to accusations of plagiarism (the primary reason, it’s been opined, that THE WHITE HOTEL lost the coveted Booker Prize in 1981, coming in second to Salman Rushdie’s MIDNIGHT’S CHILDREN).

up by the occupying Nazis, and thrust into the 1941 massacre at Babi Yar. This section, the book’s most “terribly severe” (as claimed in a back cover blurb by Holocaust scholar Terrence des Pres), was admittedly inspired by BABI YAR, Anatoly Kuznetsov’s quasi-fictional rendering of the massacre, which has led to accusations of plagiarism (the primary reason, it’s been opined, that THE WHITE HOTEL lost the coveted Booker Prize in 1981, coming in second to Salman Rushdie’s MIDNIGHT’S CHILDREN).

In the final chapter Thomas returns to the dreamscape of the earlier pages, and a final visit to the white hotel. The effect isn’t nearly as jarring as it might have been in the hands of a less skilled writer; in fact, the tonal gist, which moves gradually from surreal fantasy to unbearable reality only to wind up in the former category, feels just right.

The novel’s success was such that, needless to say, Hollywood came calling. THE WHITE HOTEL’s (very) rocky, and thus far unfulfilled, journey to the screen is a saga as odd and unpredictable as the events related in its pages. D.M. Thomas, in fact, wrote a 4500 word Guardian published essay, “Celluloid Dreams,” in 2004, and later an entire book, 2008’s BLEAK HOTEL, about the attempted filming of his masterpiece. It involved Thomas partnering, unwisely as it turned out, with the none-too-dynamic producing duo of Bobby Geisler and John Roberdeau. This led to an eighteen year odyssey that saw Thomas become embroiled in a lawsuit brought about by Geisler and Roberdeau’s shady business practices, which drained his finances and wasted no small amount of time.

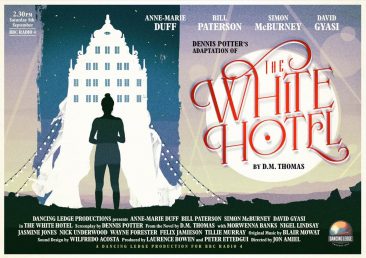

Also involved in THE WHITE HOTEL’s attempted filming were numerous great directors (Bernardo Bertolucci, David Lynch, Hector Babenco, Emir Kusturica, Pedro Almodovar, David Cronenberg, Philippe Mora), just as many top-flight actors (Barbara Streisand, Isabella Rossellini, Juliette Binoche, Kate Winslet, Tilda Swinton, Anthony Hopkins) and a much-admired screenplay adaptation by the late Dennis Potter. That 1990 script never made it to the screen, but was given an audio dramatization on BBC Radio 4, directed by Jon Amiel (of Potter’s SINGING DETECTIVE).

Detailed in BLEAK HOTEL are the upheavals in Thomas’s life that occurred during THE WHITE HOTEL’s development hell. They include the mid-1980s incarceration of Thomas’s son Sean (based, he maintained, on a false charge) and the 1998 death of his wife Denise, who apparently provided the inspiration for Lisa and haunts the pages of BLEAK HOTEL. Also featured are Thomas’s uncensored thoughts on Potter’s WHITE HOTEL script.

Detailed in BLEAK HOTEL are the upheavals in Thomas’s life that occurred during THE WHITE HOTEL’s development hell. They include the mid-1980s incarceration of Thomas’s son Sean (based, he maintained, on a false charge) and the 1998 death of his wife Denise, who apparently provided the inspiration for Lisa and haunts the pages of BLEAK HOTEL. Also featured are Thomas’s uncensored thoughts on Potter’s WHITE HOTEL script.

According to Thomas, “When I was sent Potter’s screenplay, I was dismayed to find Freud and Vienna deleted, and my operatic heroine now a high-wire act in a Berlin circus.” A faithful adaptation the screenplay isn’t, but it is pure Dennis Potter, a sustained fever dream that mixes reality, fantasy, past, present and future into a sustained hallucination a la previous Potter masterworks like THE SINGING DETECTIVE and BLACKEYES.

In some respects Potter actually improves upon the novel. The script’s constant flash-forwards to the events at Babi Yar seem irritating and even inappropriate at first, but come to harmonize quite well, showing quite conclusively that the heroine’s clairvoyant “talents” are as responsible for her condition as anything else (an aspect that was left unclear in the novel), and rendering the climactic horrors a bit less jarring than those of the text. This portion of the script, incidentally, is easily the most faithful novel-to-screenplay transposition to be found in these pages (although Potter omits the passage in which Lisa’s corpse, in a gruesome capper to the sexual content of the earlier part of the book, is violated with the tip of a Nazi soldier’s bayonet).

Another plus for Potter’s script is its seamless BBC radio transposition. The program, broadcast on September 8, 2018, was preceded by a fourteen minute preamble entitled THE LONG ROAD TO THE WHITE HOTEL, in which D.M. Thomas discusses the novel’s reception. He also speaks of Potter’s adaptation, about which he seems far more upbeat than he was in BLEAK HOTEL: “I shall feel that this is not quite THE WHITE HOTEL, but then, what adaptation ever is? And Potter, where he was very good in his screenplay, I thought, was in the sexual fantasy scenes.” Thomas is joined in the preamble by Amanda Bale and Jon Amiel, who warns that the following is “Not a show for the sexually squeamish.”

Another plus for Potter’s script is its seamless BBC radio transposition. The program, broadcast on September 8, 2018, was preceded by a fourteen minute preamble entitled THE LONG ROAD TO THE WHITE HOTEL, in which D.M. Thomas discusses the novel’s reception. He also speaks of Potter’s adaptation, about which he seems far more upbeat than he was in BLEAK HOTEL: “I shall feel that this is not quite THE WHITE HOTEL, but then, what adaptation ever is? And Potter, where he was very good in his screenplay, I thought, was in the sexual fantasy scenes.” Thomas is joined in the preamble by Amanda Bale and Jon Amiel, who warns that the following is “Not a show for the sexually squeamish.”

Well voiced by actress Anne-Marie Duff as Lisa, the audio WHITE HOTEL is slick, punchy and economical, running a pain-free 100 minutes. Featured are well modulated sound effects, excerpts from the 1930s pop tunes so integral to Potter’s universe, and narration by Simon McBurney that keeps the meat of Potter’s descriptions intact while wisely omitting the screen directions—and, as promised by Amiel, doesn’t hold back on the sexual content.

Unfortunately this program appears to have all-but vanished from circulation. That’s in direct contrast to its source text, which is still in print—as it has been for virtually the entirety of its near-40 year existence. It’s worth reading in any format, although the amazing Fred Marcellino cover so widely credited with kick-starting the book’s popularity has never been reprinted. Here’s hoping that situation is remedied in future editions of THE WHITE HOTEL, but for now prospective readers are urged to invest in a first edition. Yes, early editions of this book are still extent, and well worth your while to look upon and be amazed.