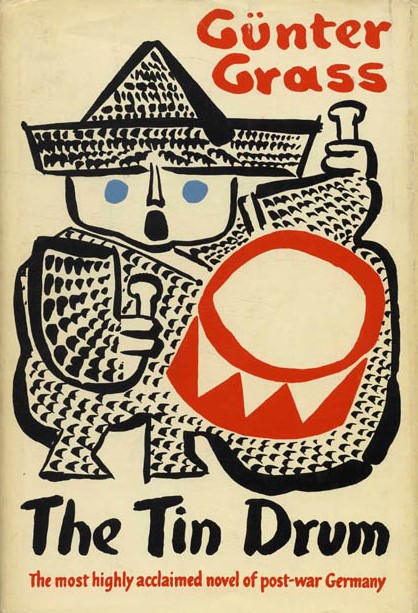

THE TIN DRUM (DIE BLECHTROMMEL) by Gunter Grass has been widely acclaimed as the greatest German novel since the end of WWII. Originally published in 1959 (and translated into English in 1961), it was Grass’s first novel, and the start of his Danzig trilogy (which concluded with CAT AND MOUSE and DOG YEARS). It’s certainly provocative, dwelling relentlessly upon death, insanity and the grotesque, and appropriately so given its Nazi-occupied WWII setting.

THE TIN DRUM (DIE BLECHTROMMEL) by Gunter Grass has been widely acclaimed as the greatest German novel since the end of WWII. Originally published in 1959 (and translated into English in 1961), it was Grass’s first novel, and the start of his Danzig trilogy (which concluded with CAT AND MOUSE and DOG YEARS). It’s certainly provocative, dwelling relentlessly upon death, insanity and the grotesque, and appropriately so given its Nazi-occupied WWII setting.

In some respects it’s a surprise THE TIN DRUM has entered the Great Novels pantheon, what with its nasty, perverse edge that apparently scandalized many late-1950s readers. Yet the holocaust setting and the author’s love of esoteric wordplay (evident in an extended rumination on the many uses of “ersatz,” to cite but one example) undoubtedly scored it some major points with the literati. Of course, Gunter Grass’s reputation took something of a hit in 2006, when he admitted that as a teenager he served in the Waffen SS, an especially shocking revelation given that Grass has been quite outspoken in denouncing fascism, but THE TIN DRUM retains its exalted reputation.

The novel is not undeserving of the acclaim, boasting an imaginative richness and descriptive power that modern novelists would do well to study. Its aura of straight-faced absurdism is equally impressive, although the novels of longtime Gunter Grass enthusiast John Irving, as well as Grass’ own subsequent efforts, have diluted the effect somewhat.

The subject is a boy named Oskar Matzerath, raised (as was Gunter Grass) in 1930s Danzig, who decides to stop growing at age 3. Oskar is gifted with a shriek that can shatter glass, and constantly beats a tin drum that functions both as a primitive means of communication and an outlet for its user’s frustrations-–or at least, so claims the grown-up Oskar, who resides in an insane asylum.

That his account may be somewhat less than reliable is indicated by the fantastical nature of the story, and also the fact that the point of view constantly switches between the first and third person, often in the same sentence. In this manner we learn how the three-year-old Oskar used his voice and drum to make trouble for the Nazis occupying Danzig, witnessed his mother go mad and eat herself to death after seeing a washed-up horse’s head swarming with eels, had a tempestuous love affair with his widowed father’s second wife Maria, and joined a gang of youthful miscreants who called him Jesus. Oskar eventually sires a child, who by beaming his father in the head with a rock causes him to start growing again-–an occurrence that coincides, appropriately enough, with the end of WWII.

In his new, only slightly more mature guise Oskar becomes a headstone engraver, artists’ model and music star. He also takes to carrying around the severed finger of a murdered nun, which precipitates his downfall, landing him in the asylum from which he dictates the preceding account. These latter passages, unfortunately, are something of a letdown, winding things up on an anticlimactic note that pales in light of the extravagant grotesquerie of the earlier pages.

Through it all Oskar remains a fascinating enigma, witty and empathetic yet also quite selfish and even somewhat despicable. Grass has reportedly stated the character represents “the revolt of the German middle class,” which according to many historians was directly responsible for the ascension of Adolph Hitler; the character is also evocative, I’m certain, of Grass’s conflicted feelings about his own WWII exploits. It’s Oskar, in any event, with all his foibles and eccentricities, that makes THE TIN DRUM such an impacting read, even when the storytelling doesn’t quite hold up.

__________ __________

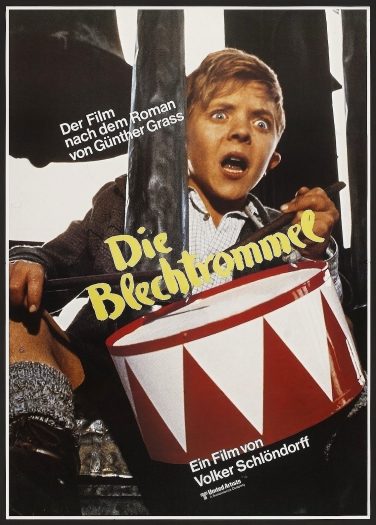

20 years after THE TIN DRUM’S initial publication a film adaptation was released. That film is now a classic in its own right, being an  extremely rare example of a movie that fully matches its source material in originality and audacity.

extremely rare example of a movie that fully matches its source material in originality and audacity.

Directed by Volker Schlondorff, who specializes in ambitious literary adaptations (including SWANN IN LOVE, THE HANDMAID’S TALE and THE OGRE, none of which can hope to approach the power of THE TIN DRUM), the film is a brilliant creation. It boasts a real sense of style, and a screenplay that adroitly captures the novel’s good qualities (the eel-infested horse head is transposed to the screen with remarkable exactness) and just as adroitly discards the not-so-good things (such as the overlong prologue detailing the exploits of Oskar’s firebug grandfather and the post-WWII sections, which as previously stated are a bit plodding).

Ultimately, however, the key to the film’s effectiveness is identical to that of the book: its furiously mercurial lead character. The 11-year-old David Bennett delivers a stunning performance as Oskar, inspiring sympathy and revulsion in equal amounts. The film doesn’t shy away from Oskar’s oft-cruel and unpleasant nature, and neither does Bennett, whose complex rendering of this character is accomplished with a skill that belies his age.

As with the novel, the film received a degree of acclaim that was surprising given its aberrant edge, including the grand prize at the Cannes Film Festival and, even more unexpectedly, the Academy Award for Best Foreign Film. Yet any film as unashamedly freakish and bizarre as THE TIN DRUM is bound to cause trouble at some point, and trouble did indeed occur in Ontario, Canada, where it was censored in 1980, and again in Oklahoma City, circa 1997.

In the latter case a judge, one Richard Freeman, banned THE TIN DRUM in Oklahoma County after a local religious group complained about it. Freeman admittedly didn’t bother viewing the entire film, explaining: “they said it could be judged pornographic, and that’s all I needed to hear.” The catalyst for the complaint was an implied depiction of oral sex between Oskar and Maria that is in truth notably tasteful and discreet (especially in comparison with the equivalent passage in the novel, which concludes with Maria gleefully picking pubic hairs from Oskar’s teeth). Nonetheless, VHS copies of THE TIN DRUM were seized from Oklahoma libraries, video stores and at least one private home. After a few months the ban was overturned and the copies all returned to their rightful owners, but (to borrow a quote from my own late-nineties reportage of the case in Gauntlet magazine) “the corrupt and unconstitutional system that spawned the ban remains firmly in place.”

So does THE TIN DRUM, in both literary and cinematic form, proving that Great Literature/Film can on occasion impact our culture in the manner of a down-and-dirty exploitation item. In this respect THE TIN DRUM ranks with the likes of LOLITA, NAKED LUNCH and LAST EXIT TO BROOKLYN on the one hand, and CHAINSAW TERROR, SLOB and AMERICAN PSYCHO on the other.