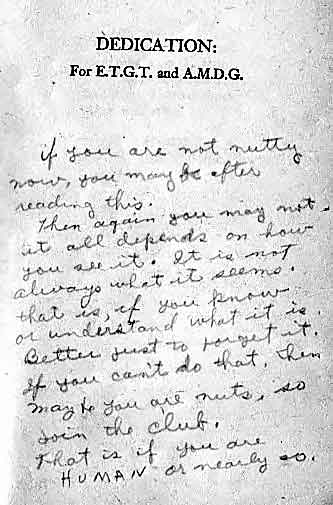

“If you are not nutty now, you may be after reading this.” So beings an extremely apropos handwritten screed found on the dedication page of a used copy of William Peter Blatty’s TWINKLE, TWINKLE, “KILLER” KANE.

“If you are not nutty now, you may be after reading this.” So beings an extremely apropos handwritten screed found on the dedication page of a used copy of William Peter Blatty’s TWINKLE, TWINKLE, “KILLER” KANE.

“If you are not nutty now, you may be after reading this.”

This bizarre tale’s inception was via a comedic novel of that title, published in 1966 and reissued in 1973. In 1978 Blatty retooled the material, resulting in THE NINTH CONFIGURATION, which contained a short preface that dismissed its previous incarnation as “no more than the notes for a novel—some sketches, unformed, unfinished, lacking even a plot,” while “This time I know it is the best I can do.”

Years later Blatty changed his mind, claiming he preferred TWINKLE, TWINKLE, “KILLER” KANE, as it was “infinitely funnier and wilder, and stranger and more of a one of a kind” than THE NINTH CONFIGURATION. Nonetheless, outside a 2010 omnibus publication of both novels by Centipede Press, TWINKLE, TWINKLE… is currently MIA, while THE NINTH CONFIGURATION is republished in trade paperback and ebook format, by Tor.

Of course there’s also the 1979 film Blatty made from the latter novel, which has (rightfully in my view) eclipsed both books in popularity, and which Blatty has dubbed his “masterpiece.”

TWINKLE, TWINKLE, “KILLER” KANE: that punctuation-heavy title is entirely appropriate to the text–-all that’s missing is an exclamation point (which in truth was included in the book’s initial 1966 publication, yet removed from all subsequent editions). The subject is madness: its onset, causes and possible cures, and how those things relate to the problem of evil.

Insanity in fiction and film was in vogue in the 1960s: see the novels CATCH-22 and ONE FLEW OVER THE CUCKOO’S NEST and the films DAVID AND LISA and KING OF HEARTS. TWINKLE, TWINKLE, “KILLER” KANE is in many respects the most audacious entry of them all, being possibly the first-ever fictional treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder among Vietnam veterans, and packed with comedic philosophical discourse (Blatty, let’s not forget, began his career as a comedy scribe) that underlies its true concern: the existence (or not) of God in the modern world.

Insanity in fiction and film was in vogue in the 1960s: see the novels CATCH-22 and ONE FLEW OVER THE CUCKOO’S NEST and the films DAVID AND LISA and KING OF HEARTS. TWINKLE, TWINKLE, “KILLER” KANE is in many respects the most audacious entry of them all, being possibly the first-ever fictional treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder among Vietnam veterans, and packed with comedic philosophical discourse (Blatty, let’s not forget, began his career as a comedy scribe) that underlies its true concern: the existence (or not) of God in the modern world.

Insanity in fiction and film was in vogue in the 1960s…

Pretty weighty stuff from a writer who back in 1966 was best known for co-scripting A SHOT IN THE DARK—a title, incidentally, that seems an apt description of Blatty’s approach to writing the quasi-experimental TWINKLE, TWINKLE…. Fragmentary, sloppy and formless though it is, the novel is also arrestingly witty and idiosyncratic, with theological arguments given equal weight to nonsensical discussions about Hamlet’s mental state.

The setting is a forbidding mansion formerly owned by deceased horror movie icon Bela Slovic. The place retains the forbidding atmosphere bequeathed by Slovik, which proves curiously appropriate to its new residents: a gaggle of mental patients hailing from various branches of the military. This makeshift asylum is run by the government, who send a renowned Marine psychiatrist to oversee the nutters—but a mistake is made, and they wind up with Colonel “Killer” Kane, a severely traumatized Nam vet loonier than any of his so-called patients.

Kane’s attempts at bonding with the inmates are naturally somewhat less-than-successful. This is particularly true in the case of Captain Cutshaw, an astronaut who was institutionalized after inexplicably aborting a moon mission (and also stumbling into a restaurant where one of his superiors was eating, drawing a line of ketchup across his throat and gurgling “Don’t order the swordfish”). Cutshaw’s biggest problem is with God—or, as he identifies Him to the staunchly Catholic Kane, Foot (“I believe I capitalized the F,” Cutshaw claims)—in whom Cutshaw steadfastly refuses to believe.

Kane’s attempts at bonding with the inmates are naturally somewhat less-than-successful. This is particularly true in the case of Captain Cutshaw, an astronaut who was institutionalized after inexplicably aborting a moon mission (and also stumbling into a restaurant where one of his superiors was eating, drawing a line of ketchup across his throat and gurgling “Don’t order the swordfish”). Cutshaw’s biggest problem is with God—or, as he identifies Him to the staunchly Catholic Kane, Foot (“I believe I capitalized the F,” Cutshaw claims)—in whom Cutshaw steadfastly refuses to believe.

An increasingly desperate Kane devises a form of “therapy” in which the patients are encouraged to give their delusions free reign. This results in a GREAT ESCAPE-inspired tunnel dig that uncovers a secret room where Bela Slovik’s presence is still evident. Kane is eventually driven completely bonkers, and enacts a sacrifice that has the paradoxical effect of setting things right among his patients, and leads to a most unlikely happy ending.

Blatty, it must be said, was and is a dedicated Catholic, and his faith is very much in evidence in both TWINKLE, TWINKLE… and THE NINTH CONFIGURATION. I imagine this will annoy many readers, especially since Blatty’s frequent attempts at using science to prove the existence of God aren’t always persuasive. (Note the concept that provides the NINTH CONFIGURATION title and figures into both novels, positing that the laws of probability involved in the spontaneous creation of life are so astronomical that, according to Kane/Blatty, entertaining such a theorem is “far more fantastic than simply believing in a God”—a rationale that could well be used as an argument in favor of atheism.) Nonetheless, it’s this strongly held sense of faith that gives TWINKLE, TWINKLE, “KILLER” KANE its edge.

As promised, this novel rectifies many of the irritants of TWINKLE, TWINKLE…. The characters are the same and the overall structure kept largely intact, yet there are many notable changes.

As promised, this novel rectifies many of the irritants of TWINKLE, TWINKLE…. The characters are the same and the overall structure kept largely intact, yet there are many notable changes.

For starters, THE NINTH CONFIGURATION is much shorter than the earlier novel, and more succinct. Much of the inmates’ semi-coherent blather has been pared down, and Kane’s mental state is presented with more clarity. Here Kane is given an imaginary twin brother who embodies his “Killer Kane” persona, and (unlike in TWINKLE, TWINKLE…) we actually get to see Killer Kane return to the fore in a stunningly violent climax.

For starters, THE NINTH CONFIGURATION is much shorter than the earlier novel, and more succinct. Much of the inmates’ semi-coherent blather has been pared down, and Kane’s mental state is presented with more clarity. Here Kane is given an imaginary twin brother who embodies his “Killer Kane” persona, and (unlike in TWINKLE, TWINKLE…) we actually get to see Killer Kane return to the fore in a stunningly violent climax.

For starters, THE NINTH CONFIGURATION is much shorter than the earlier novel, and more succinct.

The above are examples of good alterations made to TWINKLE, TWINKLE…. Unfortunately not all the tweaks are as agreeable.

In THE NINTH CONFIGURATION the overall rationale for Kane’s presence in the mansion was changed. The new explanation, positing that Kane’s psychiatrist brother (this one a real person) set up the gambit in order to cure Kane of his delusions, is even more implausible than the earlier book’s accidental placement of Kane. The mansion where the madness occurs is no longer the former residence of an ex-horror icon but an abandoned replica of a medieval German castle, which robs us of the discovery of Bela Slovic’s secret sanctum (certainly one of TWINKLE, TWINKLE…’s most effective passages). Another problem is with the aforementioned violent climax, which takes place in a bar stocked by stereotypical bikers (the 1970s equivalent of today’s gangbangers and/or terrorists), meaning the insanity in the mansion never reaches the apex it does in the earlier novel.

Blatty also insists on positioning THE NINTH CONFIGURATION as a sequel of sorts to THE EXORCIST (the middle portion, in fact, of a “trilogy of faith” that concluded with 1983’s LEGION), with Cutshaw the disturbed astronaut made into the astronaut character who gets humiliated in THE EXORCIST. The two novels, however, couldn’t be more different in style and tone. (TWINKLE, TWINKLE, “KILLER” KANE is actually much closer, and even contains a passage about exorcism in the modern world that was incorporated into THE EXORCIST.)

Ultimately I’ll have to say I prefer TWINKLE, TWINKLE, “KILLER” KANE, raggedy though it is, to THE NINTH CONFIGURATION. It’s not, however, the definitive expression of the material, which for whatever reason works best in filmic form.

Ultimately I’ll have to say I prefer TWINKLE, TWINKLE, “KILLER” KANE, raggedy though it is, to THE NINTH CONFIGURATION.

THE NINTH CONFIGURATION film, an extremely faithful adaptation of the latter novel, was Blatty’s filmmaking debut, and while his inexperience is often painfully apparent, it remains a one-of-a-kind cinematic masterwork. All the beats of the novel(s) are hit, but the film has a verve and visual pizzazz that set it apart, and a more succinct conclusion than either book.

The film was largely self-financed by Blatty, who allegedly sold a house in Malibu to raise the funds. The material’s anarchic spirit was reflected in the Budapest shoot, beset as it reportedly was by wonton drunkenness and a crucial last-minute casting change (with lead actor Nicole Williamson replaced by Stacy Keach); according to co-star Tom Atkins, “I have always believed that a movie about the making of that film would have been much better than the actual movie turned out to be.”

The film was largely self-financed by Blatty, who allegedly sold a house in Malibu to raise the funds. The material’s anarchic spirit was reflected in the Budapest shoot, beset as it reportedly was by wonton drunkenness and a crucial last-minute casting change (with lead actor Nicole Williamson replaced by Stacy Keach); according to co-star Tom Atkins, “I have always believed that a movie about the making of that film would have been much better than the actual movie turned out to be.”

Further strife accompanied the film’s 1980 release, during which it was abandoned by its initial distributor Warner Bros. and exhibited in a number of different versions. That situation remained in effect during the film’s initial home video release; finding a director’s cut was something of a chore during the VHS era, although Blatty assures us the 2002 Warners’ DVD version is the definitive one.

Stacey Keach, with his eerily somnambulant, disturbed air, perfectly embodies Kane (and delivers a hilariously deadpan recitation of the above-mentioned swordfish line). Other memorable performances are achieved by Scott Wilson (as Cutshaw), THE EXORCIST’S late Jason Miller, Robert Loggia, Moses Gunn and Joe Spinnell.

Another highlight is the climactic bar fight, which doesn’t improve on the equivalent passage in the NINTH CONFIGURATION novel—the biker antagonists are if anything more stereotypical than those of the text—but does contain some of the finest, most punishing fight choreography you’ll ever see.

…some of the finest, most punishing fight choreography you’ll ever see.

So again, I assert that THE NINTH CONFIGURATION receives its finest rendition in the bewildering, audacious and astounding film of that title. But the two novels that preceded it, TWINKLE, TWINKLE, “KILLER” KANE in particular, are definitely worth a look.