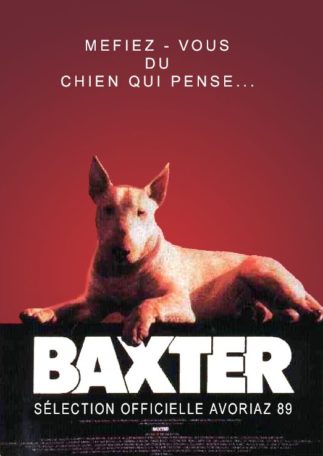

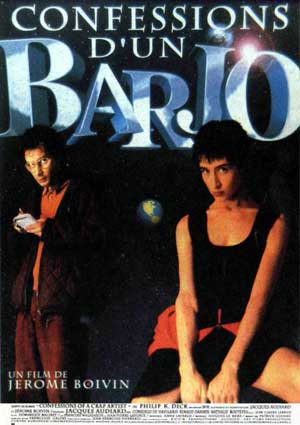

Continuing with my takes on cinematic underachievers, we come to France’s Jerome Boivin. A uniquely gifted filmmaker with a twisted comedic sensibility as distinct as those of more celebrated European auteurs like Eloy de la Iglesia and Albert Dupontel, Boivin has to date made just two features: 1988’s BAXTER and 1992’s CONFESSIONS D’UN BARJO (or, as it’s known in the US, BARJO). Both were impressive enough that, as a 1993 Film Comment article on Boivin claimed, “Drawing a line from (Boivin’s first film) to his second and extending it into space, the trajectory could prove stratospheric.” Sadly, we never got a chance to witness that trajectory, as following BARJO Boivin became stuck in the French TV arena, seemingly indefinitely.

with a twisted comedic sensibility as distinct as those of more celebrated European auteurs like Eloy de la Iglesia and Albert Dupontel, Boivin has to date made just two features: 1988’s BAXTER and 1992’s CONFESSIONS D’UN BARJO (or, as it’s known in the US, BARJO). Both were impressive enough that, as a 1993 Film Comment article on Boivin claimed, “Drawing a line from (Boivin’s first film) to his second and extending it into space, the trajectory could prove stratospheric.” Sadly, we never got a chance to witness that trajectory, as following BARJO Boivin became stuck in the French TV arena, seemingly indefinitely.

I haven’t seen any of Boivin’s work for the small screen, consisting of two episodic TV programs and four TV movies, but it doesn’t sound too promising. His 1998 TV movie LA COURSE DE L’ESCARGOT, for instance, was described by an imdb user as being about “an unemployed man (who) finds work and happiness in the countryside”…a far cry from the twisted brilliance of BAXTER and BARJO.

I’m tempted to blame Boivin himself for his lack of productivity over the ensuing twenty-plus years, but I think the fault is more properly with the French film industry as a whole. To filmmakers toiling in Hollywood, where profit is king, a government-sponsored film outfit whose decisions are artistically motivated, as is the case in France, might seem idyllic. That attitude, however, ignores the realities of the French film industry, whose decisions on what gets made tend to be arbitrary and often downright capricious. Perhaps we should be thankful that Boivin managed to complete two features; his similarly oriented French filmmaker colleague Alain Robak (who has a cameo appearance in BARJO) managed to make just one, 1990’s impressive BABY BLOOD, before vanishing from sight.

Both BAXTER and BARJO were adapted from American novels, the first from Ken Greenhall’s 1977 HELL HOUND and the second from Philip K. Dick’s 1975 CONFESSIONS OF A CRAP ARTIST. The two films are remarkably similar in conception, distinguished by cockeyed views of suburban life processed through the sensibilities of two thoroughly idiosyncratic protagonists: a bull terrier who thinks like a human and a severely maladjusted man-child.

In the case of BAXTER the protagonist, the aforementioned bull terrier, is thoroughly evil. Flawlessly voiced by Maxim Leroux, Baxter is a moody, gravelly-voiced sort whose thoughts are rendered in the form of voice-over narration, a device that (for once) works quite well onscreen.

In the case of BAXTER the protagonist, the aforementioned bull terrier, is thoroughly evil. Flawlessly voiced by Maxim Leroux, Baxter is a moody, gravelly-voiced sort whose thoughts are rendered in the form of voice-over narration, a device that (for once) works quite well onscreen.

Early on in his life Baxter is taken from the kennel where he was brought up and placed in the company of an old woman (Lise Delamare) he despises. He knocks the old bag down the stairs, putting an end to her hated existence, and is transferred to a young couple. Baxter’s days with them are idyllic, at least until the woman becomes pregnant and gives birth to a child Baxter finds repulsive. He tries to drown the baby in a backyard pond, but barks for help too soon, inadvertently saving the kid’s life.

Finding that Baxter’s presence evokes painful memories of the accident, the couple elect to give him away. Baxter ends up in the care of a deranged Hitler-obsessed boy (Francis Driancourt), and takes well to the harsh, disciplined lifestyle enforced by his new master. Said master meets up with a comely girl who reminds him of Eva Braun, and whose female dog is jumped by Baxter. A litter of puppies is born, but the boy kills them all, driving a wedge between him and Baxter that only deepens as time goes on. Clearly, a boy-dog showdown is evident, a confrontation only one of them will survive.

BAXTER’S primary strengths are in its compellingly naturalistic atmosphere and solid performances. A subtly surreal aura is provided by periodic fantasy sequences, such as one wherein a dead woman appears beside her widowed husband beckoning him to the beyond, and also the black and white specter of Eva Braun that haunts the dreams of Baxter’s youthful master.

BAXTER was a freshman effort, however, and Boivin’s inexperience is evident in the perfunctory storytelling and pacing that’s a bit too brisk for its own good, which more often than not has the effect of reducing a complex satire on the wily nature of evil to a sub-Monty Pythonesque exercise in gross-out absurdity. The staging isn’t always up to par, either: the final boy-dog face off in particular is a bit of a bust, an epic confrontation in the Greenhall novel that onscreen is wheedled down to a minute or so of shouting and hurled debris.

What ultimately redeems the film is its peerlessly audacious narrative, bequeathed from Ken Greenhall’s amazing text. Boivin was wise to stick so closely to it, creating something increasingly rare in today’s movie marketplace: a totally original.

BARJO was likewise a fairly faithful adaptation of its source material, one of a handful of non-science fiction oriented  novels by Philip K. Dick (and the only one of them to be published in the author’s lifetime). Both the Dick novel and Boivin film are related from the viewpoint of the eponymous “crap artist,” a deeply eccentric young man who collects worthless esoteria to support his contention that aliens are about to blow up the sun. As in BAXTER, that viewpoint is related via continuous voice-over narration by the title character, superbly incarnated by Hippolyte Giradot.

novels by Philip K. Dick (and the only one of them to be published in the author’s lifetime). Both the Dick novel and Boivin film are related from the viewpoint of the eponymous “crap artist,” a deeply eccentric young man who collects worthless esoteria to support his contention that aliens are about to blow up the sun. As in BAXTER, that viewpoint is related via continuous voice-over narration by the title character, superbly incarnated by Hippolyte Giradot.

Barjo has some stiff competition in the eccentricity department from his twin sister Fanfan, a highly strung, unpredictable hysteric who’s driving her aluminum magnate husband Charles totally batty. This relationship was apparently more than a little autobiographical on the part of Mr. Dick, whose romantic foibles are well documented (see the biographical volumes DIVINE INVASIONS by Lawrence Sutin and I AM ALIVE AND YOU ARE DEAD by Emmanuel Carrère). Boivin at least tones down the misogyny of Dick’s portrayal of Fanfan, played unforgettably by Anne Brochet.

As BARJO begins the title character’s house burns down, forcing him to move into the swank country home of Fanfan and Charles. The latter is nearly insane over Fanfan’s unpredictable behavior, and is pushed over the edge completely when Barjo moves in. In short order Fanfan becomes unhealthily obsessed with an attractive young couple (who serve the same function as the couple who tempt the protagonist of BAXTER) and Charles has a non-fatal heart attack. While he recovers in the hospital Fanfan commences an affair with the male half of the couple, and Barjo falls under the spell of a creepy mystic woman (the inverse of the evil boy in BAXTER). The climax, like that of BAXTER, is quite dark and violent, although there is a happy ending of sorts involving a ghostly visitation that, given the film’s absurdist bent, actually works.

In BARJO Boivin swapped the mirth of BAXTER with screwball comedy that’s no less pitiless or cutting. More importantly, Boivin’s confidence as a filmmaker increased markedly from BAXTER to BARJO, which is occasionally cluttered but never boring. I for one would have loved to see where that confidence might have taken this most talented and unpredictable filmmaker, but for now it looks as if we’ll have to content ourselves with these two films.