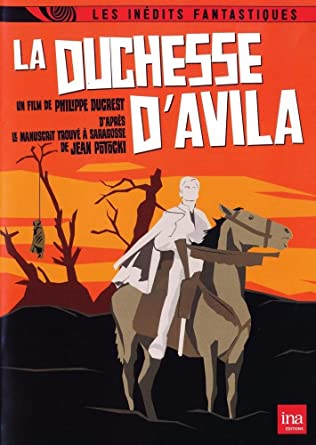

The 1973 French miniseries LA DUCHESSE D’AVILA/THE DUCHESS OF AVILA is one of the great unknown works of the fantastique. Co-scripted and directed by the late TV specialist Philippe Ducrest, the series was adapted from Count Jan Potocki’s immortal 19th Century novel THE MANUSCRIPT FOUND IN SARAGOSSA. The material turns out to be well suited to the TV miniseries format, with LA DUCHESSE D’AVILA’S six hour canvas proving an ideal vehicle for Potocki’s highly expansive, multi-character epic. Yet Ducrest, like any astute adaptor, provides his own highly idiosyncratic take on the material.

The 1973 French miniseries LA DUCHESSE D’AVILA/THE DUCHESS OF AVILA is one of the great unknown works of the fantastique. Co-scripted and directed by the late TV specialist Philippe Ducrest, the series was adapted from Count Jan Potocki’s immortal 19th Century novel THE MANUSCRIPT FOUND IN SARAGOSSA. The material turns out to be well suited to the TV miniseries format, with LA DUCHESSE D’AVILA’S six hour canvas proving an ideal vehicle for Potocki’s highly expansive, multi-character epic. Yet Ducrest, like any astute adaptor, provides his own highly idiosyncratic take on the material.

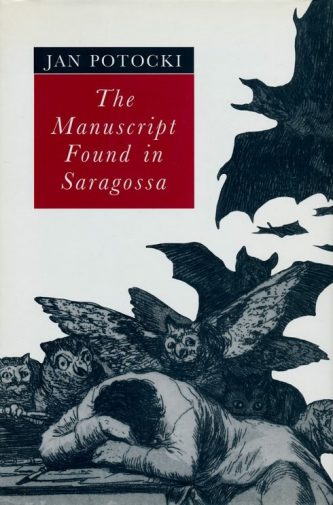

Count Jan Potocki (1761-1815) was a Polish nobleman whose life was every bit as exciting and incident-filled as that of the protagonist of THE MANUSCRIPT FOUND IN SARAGOSSA. Said protagonist is Alphonse van Worden, a Spanish officer afoot in a vast desert in 1739, where he’s made complicit in the fantastic and macabre affairs of a vast array of characters whose stories Alphonse dutifully transcribes, resulting in the text under discussion. It spans several millennia and contains a couple dozen narrators, as well as a narrative that frequently loops in on itself and alternates stories-within-stories in a manner so intricate many of the characters are moved to comment on it.

Count Jan Potocki (1761-1815) was a Polish nobleman whose life was every bit as exciting and incident-filled as that of the protagonist of THE MANUSCRIPT FOUND IN SARAGOSSA.

Completed around the time of its author’s alleged 1815 suicide, THE MANUSCRIPT FOUND IN SARAGOSSA was drafted  in French yet initially survived only in a Polish translation of Potocki’s original text by Edmund Chojecki. Initial publications of the novel were of varying degrees of completeness, with the most common version, entitled THE SARAGOSSA MANUSCRIPT, running about a third of the work’s full length. It wasn’t until 1989 that an authoritative text of THE MANUSCRIPT FOUND IN SARAGOSSA was published in France, courtesy of editor Rene Radrizzani. An English translation appeared in 1995, which remains the most recent English version, even though an even more complete French language text appeared in 2008, pieced together by Francois Rosset and Dominique Triaire from writings by Potocki himself (as opposed to Edmund Chojecki’s translations of same).

in French yet initially survived only in a Polish translation of Potocki’s original text by Edmund Chojecki. Initial publications of the novel were of varying degrees of completeness, with the most common version, entitled THE SARAGOSSA MANUSCRIPT, running about a third of the work’s full length. It wasn’t until 1989 that an authoritative text of THE MANUSCRIPT FOUND IN SARAGOSSA was published in France, courtesy of editor Rene Radrizzani. An English translation appeared in 1995, which remains the most recent English version, even though an even more complete French language text appeared in 2008, pieced together by Francois Rosset and Dominique Triaire from writings by Potocki himself (as opposed to Edmund Chojecki’s translations of same).

THE SARAGOSSA MANUSCRIPT, Polish maestro Wojciech Has’ legendary filming of Potocki’s masterpiece, came about in 1965. Adroitly capturing the novel’s horrific whimsy, the film was a sumptuous and energetic three hour riot of ghosts, ghouls, derring-do and gorgeous landscapes. Has’ visual brilliance, subsequently demonstrated in films like LALKA (1968) and THE HOURGLASS SANATORIUM (1973), was in full bloom here, resulting in what was very likely his finest-ever work in the cinema.

THE SARAGOSSA MANUSCRIPT was a sizeable hit on the counterculture circuit—it was a favorite of Luis Bunuel and the Grateful Dead’s late headliner Jerry Garcia—during its initial (cut) US release in 1972. It was re-released in 1999 through the efforts of Francis Ford Coppola and Martin Scorsese, whose names are prominently displayed on the Image DVD release. It’s just too bad Coppola and Scorsese didn’t do the same for LA DUCHESSE D’AVILA.

THE SARAGOSSA MANUSCRIPT was a sizeable hit on the counterculture circuit—it was a favorite of Luis Bunuel and the Grateful Dead’s late headliner Jerry Garcia—during its initial (cut) US release in 1972.

LA DUCHESSE D’AVILA certainly matched THE SARAGOSSA MANUSCRIPT in extravagance and invention, but was not as warmly received. Despite being the most lavish and expensive French television production of its time—it cost a  reported 600 million francs and its filming lasted a full year—it never received much play outside France. Initially broadcast in July of 1973, the series was widely criticized for what many critics viewed as a needlessly extravagant budgetary overlay and production background, and took until 2012 to receive a French-only DVD release (to date its only home video presence).

reported 600 million francs and its filming lasted a full year—it never received much play outside France. Initially broadcast in July of 1973, the series was widely criticized for what many critics viewed as a needlessly extravagant budgetary overlay and production background, and took until 2012 to receive a French-only DVD release (to date its only home video presence).

The approach taken by Philippe Ducrest diverges mightily from that of Wojciech Has, with the overlapping stories motif toned down considerably. In LA DUCHESS D’AVILA’S first part, lasting around 70 minutes, we’re introduced to Jean Blaise as Alphonse van Worden, who’s looking to follow in the footsteps of his dashing Lieutenant-Colonel father. The latter is deeply concerned about his son’s credentials as a swordsman, and, following a succession of practice swordfights, Alphonse is sent off on horseback to join the Spanish army in Madrid. Alphonse dutifully sets off with two traveling companions, both of whom get lost in the desert of Sierra Morena, which is allegedly haunted by the unquiet spirits of two brothers who were hanged in the area.

Curiously enough, outside the warning about the unsettled spirits there’s nary a trace in part one of the fantastic machinations that come to dominate parts two and three. The art direction, at least, strongly hints at the bizzarie to come in its swirling tile floor designs, golden cloaks, mirrored rock surfaces and intricate use of shadow. Here Alphonse’s background, which was but a portion of the tapestry of the original novel and Wojciech Has movie adaptation, assumes center stage. In the material’s previous incarnations, after all, Alphonse was a largely reactive character, whereas here he assumes the role of a fully functioning hero.

It’s in LA DUCHESSE D’AVILA’S 130 minute second part that the wildness really begins. Here the supernatural enters into and suffuses the proceedings, and the film’s THE SHEIK-meets-BARBARELLA visual aesthetic really comes into its own.

It’s in LA DUCHESSE D’AVILA’S 130 minute second part that the wildness really begins.

A lphonse, stranded by himself in Sierra Morena (the very point, incidentally, at which the Potocki novel and Has film began), elects to stay the night in a strangely deserted inn, despite a handwritten sign posted outside that specifically warns against doing so. Within the inn’s garishly designed interior Alphonse meets two alluring Moorish ladies clad in overtly campy breast-bearing outfits. They ask Alphonse to meet them in dreams, and he unwisely agrees. In this way he’s led into a tortured maze of hallucinations and stories-within-stories involving a seemingly possessed man, the latter’s lecherous stepmother and a Kabbalist sorcerer, along with the two Moorish ladies, who make at least one subsequent appearance, and the two hanging corpses said to be haunting the place.

lphonse, stranded by himself in Sierra Morena (the very point, incidentally, at which the Potocki novel and Has film began), elects to stay the night in a strangely deserted inn, despite a handwritten sign posted outside that specifically warns against doing so. Within the inn’s garishly designed interior Alphonse meets two alluring Moorish ladies clad in overtly campy breast-bearing outfits. They ask Alphonse to meet them in dreams, and he unwisely agrees. In this way he’s led into a tortured maze of hallucinations and stories-within-stories involving a seemingly possessed man, the latter’s lecherous stepmother and a Kabbalist sorcerer, along with the two Moorish ladies, who make at least one subsequent appearance, and the two hanging corpses said to be haunting the place.

The highlight of this segment is a threesome between Alphonse and the two ladies, presented via a wholly bizarre interpretive dance. This involves a lot of gravity-defying bodily contortions and a golden penis head ornament worn by Alphonse, and is a standout example of Ducrest’s audacious approach. Much like Ken Russell, Ducrest has no problem skirting unintentional comedy or bad taste—indeed, he seems to positively relish doing so.

In part three, lasting 52 minutes, Alphonse is tortured by officers of the Inquisition for the crime of consorting with demons. He’s rescued by the dashing—and possibly dangerous—Zoto (Serge Marquand), a relative of the hanged brothers who leads Alphonse into an underground palace via a well filled with “dry” water. From there Alphonse and Zoto float on an underground river of quicksilver to the palace of the enigmatic Duchess of Avila (Evelyne Eyfel), a wildly psychedelic environ stocked by dwarf automatons and marked by rooms of gold, silver and marble, mirrored walls, star-lined ceilings and water flowing through ever-present glass columns. Alphonse eventually “meets” the duchess, who approaches him from behind and implores him not to turn around and face her.

In part three, lasting 52 minutes, Alphonse is tortured by officers of the Inquisition for the crime of consorting with demons. He’s rescued by the dashing—and possibly dangerous—Zoto (Serge Marquand), a relative of the hanged brothers who leads Alphonse into an underground palace via a well filled with “dry” water. From there Alphonse and Zoto float on an underground river of quicksilver to the palace of the enigmatic Duchess of Avila (Evelyne Eyfel), a wildly psychedelic environ stocked by dwarf automatons and marked by rooms of gold, silver and marble, mirrored walls, star-lined ceilings and water flowing through ever-present glass columns. Alphonse eventually “meets” the duchess, who approaches him from behind and implores him not to turn around and face her.

In the more down-to-Earth final segment, lasting 100 minutes, the impetuous Alphonse does indeed turn around to face his host. He quickly falls in love with the Duchess, who turns out to be quite the eccentric, abusing her underlings on a whim and favoring space-agey red and white dresses that look like cast-offs from Jane Jetson’s closet. Oddest of all is the fact that the duchess tries to fob Alphonse off onto her look-alike sister Leonora—a situation further complicated by the fact that the two “sisters” are actually one and the same! Alphonse also gets a chance to replicate his father’s wartime feats and fulfill his military destiny in the final scenes, depicting a massive battle with what look like thousands of horse-riding extras.

Add to that the incredibly elaborate and oft-psychedelic set design, which includes a colorful hippie pad situated inside a  desert ruin, a dwarf’s tiger and lamb flanked miniature throne room, and the Duchess of Avilla’s astounding hallucinogenic palace wherein birds swim and fish fly, and you’ve got one of the most extravagant fantasy landscapes in film history. The imagery is enhanced by a fabulously baroque visual style favoring foreground-heavy compositions that pack glittering wonders into every inch of the frame (a far cry from the sparsely detailed eye-level close-ups of most made-for-TV fare).

desert ruin, a dwarf’s tiger and lamb flanked miniature throne room, and the Duchess of Avilla’s astounding hallucinogenic palace wherein birds swim and fish fly, and you’ve got one of the most extravagant fantasy landscapes in film history. The imagery is enhanced by a fabulously baroque visual style favoring foreground-heavy compositions that pack glittering wonders into every inch of the frame (a far cry from the sparsely detailed eye-level close-ups of most made-for-TV fare).

Shortcomings? Yes, there are a few. The filmmaking, in common with many French telefilms, often lacks the polish of the more prestigious French-made features, while the generic seventies-centric score is beyond cheesy (Philippe Ducrest’s attributes evidently did not include an ear for music), and the pacing downright somnambulant even by traditional European movie standards. That latter complaint refers primarily to the agonizingly protracted and repetitive scenes of Alphonse riding his horse around the Spanish countryside that clog parts one and two, and also his equally protracted wanderings through the grounds of the duchess’s palace in part four. Ducrest’s penchant for ambiguity is another element that will surely turn off many viewers, particularly in the last scene, which closes the film out with a real noggin’ scratcher of a final shot.

So THE DUCHESS OF AVILA has its flaws. But for those willing to meet this one-of-a-kind mind-roaster on its own terms the rewards are many. Few other films of any sort would attempt, much less pull off, images like those on display in LA DUCHESS D’AVILA, whose sustained immersion in the fantastic and surreal remains without parallel on the big or small screen.