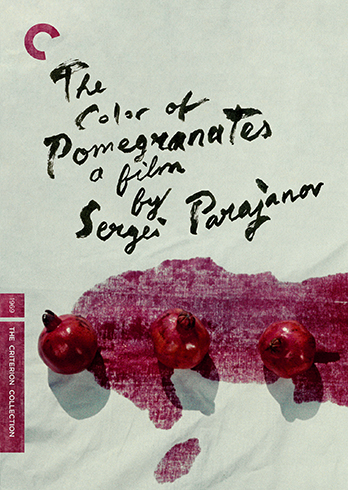

There has never been another film quite like THE COLOR OF POMEGRANATES. The signature creation of Armenia’s incomparable Sergei Parajanov (1924-1990), it began life in 1968 as SAYAT-NOVA, only to lose around 20 minutes of footage at the hands of Soviet censors and be re-christened RED POMEGRANATE (NRAN GUYNE)—or, as its better known, THE COLOR OF POMEGRANATES. The film’s early 2018 Criterion Collection DVD debut, in a newly restored and re-edited version, is unquestionably one of the most vital home video releases of recent years.

There has never been another film quite like THE COLOR OF POMEGRANATES. The signature creation of Armenia’s incomparable Sergei Parajanov (1924-1990), it began life in 1968 as SAYAT-NOVA, only to lose around 20 minutes of footage at the hands of Soviet censors and be re-christened RED POMEGRANATE (NRAN GUYNE)—or, as its better known, THE COLOR OF POMEGRANATES. The film’s early 2018 Criterion Collection DVD debut, in a newly restored and re-edited version, is unquestionably one of the most vital home video releases of recent years.

…it began life in 1968 as SAYAT-NOVA, only to lose around 20 minutes of footage at the hands of Soviet censors and be re-christened RED POMEGRANATE (NRAN GUYNE)

The film’s subject? The eighteenth century Armenian poet Harutyun Sayatyan, or Sayat-Nova, whose tortured life is dramatized from childhood to old age. THE COLOR OF POMEGRANATES is NOT, however, a traditional movie biography, being a surreal collage of tableaux-styled images that seek to approximate in visual form the nuances of Sayat-Nova’s poetry. Steeped in Armenian culture and its writer-director’s own quirks and obsessions—certainly no other Parajanov project better exemplifies the oft-repeated quote “Parajanov made films not about how things are, but how they would have been had he been God”—the film often seems impenetrable, but the limitless imagination, bold use of color, stunningly composed images and richly percussive sound design are more than enough to sustain one’s interest. Filmmaker Mikhail Vartanov claimed that “the world cinema has not discovered anything revolutionarily new until THE COLOR OF POMEGRANATES.” So revolutionary was the film, in fact, that it played a part in Parajanov’s 1973 arrest (his second) and four year internment in a Siberian labor camp.

“Parajanov made films not about how things are, but how they would have been had he been God”

THE COLOR OF POMEGRANATES followed two decades’ worth of largely uninspiring Parajanov directed films, the majority of which he subsequently dismissed as “garbage.” They included the visually striking children’s fantasy ANDRIESCH (1954) and the routine dramas UKRAINIAN RHAPSODY (UKRAINSKAYA RAPSODIYA; 1961) and LITTLE FLOWER ON A STONE (TSVETOK NA KAMNE; 1962), upon which Parajanov admittedly worked as a director-for-hire. It wasn’t until the Ukrainian SHADOWS OF FORGOTTEN ANCESTORS (TINI ZABUTYKH PREDKIV; 1965) that Parajanov evinced anything close to the cinematic mastery that found its apex in POMEGRANATES. A bold, vibrant and defiantly individual piece of work, SHADOWS OF FORGOTTEN ANCESTORS had a not-inconsiderable impact on cinema in Russia, and indeed the rest of the world.

Yet as impressive as SHADOWS was, it couldn’t possibly have prepared audiences for THE COLOR OF POMEGRATES. As previously mentioned, POMEGRANATES presents the events of Sayat-Nova’s life in more-or-less chronological order, starting with his childhood, impacted by books and dyed carpets, followed by his ascension to the royal court and ill-advised affair with the king’s sibling Ana (depicted via a bizarre string-weaving duel), and concluding with his eventual banishment, during which he became a priest and eventually died for his faith. Intertitles laying out the film’s chronology were inserted after the fact by filmmaker Sergei Yutkevich, who was charged with overseeing the reediting of THE COLOR OF POMEGRANATES.

Yet as impressive as SHADOWS was, it couldn’t possibly have prepared audiences for THE COLOR OF POMEGRATES. As previously mentioned, POMEGRANATES presents the events of Sayat-Nova’s life in more-or-less chronological order, starting with his childhood, impacted by books and dyed carpets, followed by his ascension to the royal court and ill-advised affair with the king’s sibling Ana (depicted via a bizarre string-weaving duel), and concluding with his eventual banishment, during which he became a priest and eventually died for his faith. Intertitles laying out the film’s chronology were inserted after the fact by filmmaker Sergei Yutkevich, who was charged with overseeing the reediting of THE COLOR OF POMEGRANATES.

It’s a safe bet that anyone claiming to “understand” THE COLOR OF POMEGRANATES who a). isn’t Armenian, b). hasn’t read the script, or c). hasn’t viewed the DVD supplements is lying…

Some of the seemingly-inexplicable actions we see onscreen are explained in Parajanov’s screenplay (contained in the 1992 anthology volume SEVEN VISIONS), a document that is in its own way every bit as bizarre and poetic as the finished film. A depiction of monks arising from holes in a palace floor, for instance, is revealed in the script to be part of an elaborate ritual meant to honor the Catholicoi (the leaders of the Armenian Apostolic Church), while a seemingly incoherent bit toward the end, in which Sayat Nova takes part in a funeral procession, is significant because, as the script notes, the dead woman reminds him of the image of Our Lady of Akhtala (whose face was dislodged from a mural in a previous scene).

It’s a safe bet that anyone claiming to “understand” THE COLOR OF POMEGRANATES who a). isn’t Armenian, b). hasn’t read the script, or c). hasn’t viewed the DVD supplements is lying—or perhaps just severely misinformed. Misguided interpretations have been myriad over the years, with some viewing the film as a hymn to gender neutrality, given that the title character is very clearly played in his early years by a woman (the late Sofiko Chiaureli, to be exact, who also plays Sayat-Nova’s love interest). Others claim its images of bleeding pomegranates, a knife stuck in a bloody wall and masses of crosses were meant to foreshadow the Armenian genocide of 1914-23, when in fact they refer to Sayat-Nova’s execution at the hands of the army of Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar, the Shah of Iran.

Ultimately, it makes little difference whether viewers understand Parajanov’s enigmas or not. The film’s primary fascination, after all, is in its immersive presentation of a culture so far removed from our own it often seems downright science fictionish.

Ultimately, it makes little difference whether viewers understand Parajanov’s enigmas or not. The film’s primary fascination, after all, is in its immersive presentation of a culture so far removed from our own it often seems downright science fictionish.

Parajanov liked to say that THE COLOR OF POMEGRANATES’S highly minimalistic style, marked by fixed camera compositions, pantomimed acting and VERY sparse dialogue (it was filmed M.O.S., i.e. without sound), was brought about by necessity. Soviet authorities, he claimed on more than one occasion, denied him the resources to create the extravagant vision he allegedly had in mind, and interfered throughout the production. He may well have been telling the truth on that last point, but it’s a fact that Parajanov was something of what we here in the west like to call a bullshitter. Among the other claims he made, after all, was that his 1970s-era labor camp experiences included escaping his imprisonment and hiding out in a hammer-and-sickle statue, as related in the 1991 film SWAN LAKE: THE ZONE, directed by Parajanov’s longtime frenemy Yuri Ilyenko (1936-2010). The facts don’t support that account, and nor do those regarding Parajanov’s claims about THE COLOR OF POMEGRANATES’S conception.

It’s a fact that the film’s unique style was explicitly foreshadowed in the existing portions of Parajanov’s unfinished 1965 feature KIEV FRESCOES, and laid out in the published script, so POMEGRANATES’S minimalistic formalism clearly didn’t come about by accident or necessity. Furthermore, many of the interviewees of Daniel Bird’s 2011 documentary THE WORLD IS A WINDOW: MAKING THE COLOR OF POMEGRANATES claim Parajanov was making a deliberate break with the ultra-kinetic visuals of SHADOWS OF FORGOTTEN ANCESTORS, courtesy of that film’s cinematographer, the aforementioned Yuri Ilyenko.

Ilyenko, in fact, can be said to have exerted a not-inconsiderable influence on the conception of THE COLOR OF POMEGRANATES, even though he had no direct role in its production. Ilyenko’s highly elliptical and poetic self-directed feature A SPRING FOR THE THIRSTY (RODNIK DLYA ZHAZHDUSHCHIKH; 1965), one of the key entries in the “Kiev School” of Ukrainian-made poetic cinema, stands as perhaps the closest thing that exists to a true precursor to POMEGRANATES. There’s also the fact that, as one of the interviewees of THE WORLD IS A WINDOW asserts, Parajanov had Ilyenko in mind when he conceived of POMEGRANATES’S non-showy aesthetic–particularly irksome were Ilyenko’s inflated claims about his contributions to SHADOWS OF OUR FORGOTTEN ANCESTORS, about which Parajanov wasn’t at all pleased, and which he was determined to disprove by creating a film that didn’t rely on expressive camera movement and lenses. (Ilyenko, incidentally, underwent his own COLOR OF POMEGRANATES-like experience with his 2002 directorial effort A PRAYER FOR HETMAN MAZEPA/MOLITVA ZA GETMANA MAZEPU, an expensive Ukrainian production that was widely reviled for its defiantly unorthodox take on a national hero; the film obviously isn’t on the same level as POMEGRANATES, but it is an interesting oddity that deserves to be rediscovered in the same way Parajanov’s film was).

Ilyenko, in fact, can be said to have exerted a not-inconsiderable influence on the conception of THE COLOR OF POMEGRANATES, even though he had no direct role in its production. Ilyenko’s highly elliptical and poetic self-directed feature A SPRING FOR THE THIRSTY (RODNIK DLYA ZHAZHDUSHCHIKH; 1965), one of the key entries in the “Kiev School” of Ukrainian-made poetic cinema, stands as perhaps the closest thing that exists to a true precursor to POMEGRANATES. There’s also the fact that, as one of the interviewees of THE WORLD IS A WINDOW asserts, Parajanov had Ilyenko in mind when he conceived of POMEGRANATES’S non-showy aesthetic–particularly irksome were Ilyenko’s inflated claims about his contributions to SHADOWS OF OUR FORGOTTEN ANCESTORS, about which Parajanov wasn’t at all pleased, and which he was determined to disprove by creating a film that didn’t rely on expressive camera movement and lenses. (Ilyenko, incidentally, underwent his own COLOR OF POMEGRANATES-like experience with his 2002 directorial effort A PRAYER FOR HETMAN MAZEPA/MOLITVA ZA GETMANA MAZEPU, an expensive Ukrainian production that was widely reviled for its defiantly unorthodox take on a national hero; the film obviously isn’t on the same level as POMEGRANATES, but it is an interesting oddity that deserves to be rediscovered in the same way Parajanov’s film was).

It seems that, in a further blow to Parajanov’s claims of official resistance to the production of POMEGRANATES, he was given a great deal of leeway by Soviet authorities. Note the many zoo animals that appear onscreen along with the actors, the multitude of horse-riding extras who turn up throughout and the succession of sacred temples and monasteries in which Parajanov was allowed to film. Anticipation about POMEGRANATES was apparently quite high, particularly among Armenian citizens, for whom Sayat-Nova was and remains a highly revered figure. What they thought of the finished film I don’t know, although it’s a widely known fact that the Soviets were none too thrilled.

It seems that, in a further blow to Parajanov’s claims of official resistance to the production of POMEGRANATES, he was given a great deal of leeway by Soviet authorities.

THE COLOR OF POMEGRANATES was never, as has been mistakenly claimed, “banned” outright in Russia. It did, however, suffer widespread neglect over the following decade, due mostly to the efforts of the Soviets to suppress and discredit it. Parajanov managed to complete two more feature films, THE LEGEND OF SURAM FORTRESS (AMBAVI SURAMIS TSIKHISA; 1985) and—following yet another trumped-up arrest—ASHIK KERIB (ASHIKI KERIBI; 1988), both heavily informed by the esoteric poetry he debuted in THE COLOR OF POMEGRANATES, prior to his untimely death in 1990.

THE COLOR OF POMEGRANATES was never, as has been mistakenly claimed, “banned” outright in Russia. It did, however, suffer widespread neglect over the following decade, due mostly to the efforts of the Soviets to suppress and discredit it. Parajanov managed to complete two more feature films, THE LEGEND OF SURAM FORTRESS (AMBAVI SURAMIS TSIKHISA; 1985) and—following yet another trumped-up arrest—ASHIK KERIB (ASHIKI KERIBI; 1988), both heavily informed by the esoteric poetry he debuted in THE COLOR OF POMEGRANATES, prior to his untimely death in 1990.

THE COLOR OF POMEGRANATES attained a following that steadily grew in enthusiasm during Parajanov’s final years, and even penetrated the western market. I was fortunate enough to see one of the film’s rare US theatrical screenings, held at the fabled New Beverly Cinema, in 1989, and purchase the RED POMEGRANATE monikered NTSC VHS, released through IFEX’S “Soviet Cinema Today” label (which incidentally put out quite a few vital Russian language films, such as Elem Klimov’s COME AND SEE, Rolan Bykov’s SCARECROW and Aleksandr Askoldov’s COMMISSAR).

It took until 2006 for the next important, if largely unacknowledged, chapter in the COLOR OF POMEGRANATES saga to occur. It was on October 14 of that year that the “Sayat-Nova Rushes” screened on Italy’s RAI network. Consisting of 4½ hours’ worth of sound-free footage from the film’s production, this highly unprecedented broadcast came about, it’s been rumored, through the efforts of a crafty programmer who obtained the footage by assuring the Russian copyright holders, who were loath to give it up, that he intended to use portions of it in a documentary, only to then broadcast the entire thing over the course of single night.

It took until 2006 for the next important, if largely unacknowledged, chapter in the COLOR OF POMEGRANATES saga to occur. It was on October 14 of that year that the “Sayat-Nova Rushes” screened on Italy’s RAI network. Consisting of 4½ hours’ worth of sound-free footage from the film’s production, this highly unprecedented broadcast came about, it’s been rumored, through the efforts of a crafty programmer who obtained the footage by assuring the Russian copyright holders, who were loath to give it up, that he intended to use portions of it in a documentary, only to then broadcast the entire thing over the course of single night.

The Sayat-Nova Rushes are valuable for the fact that they’re the closest we’ll ever get to seeing a true director’s cut of THE COLOR OF POMEGRANATES. Much of the footage included in the rushes is present in the finished film, but there’s much that isn’t. A lot of the unseen footage, unsurprisingly, is concerned with Sayat-Nova’s sexual orientation, which was apparently far from straight (thus explaining why Soviet authorities discarded this footage)—as in scenes where he shuns women in favor of his fellow sex and, in the most striking of the never-before-seen clips, a bit in which Sayat splashes a bucket of milk on a glass pane, before which stands an alluringly ominous woman (Parajanov termed this the “nocturnal emission” scene). Also present are the expected alternate takes and rehearsal footage, none of which is presented in any sort of order. Nonetheless, these rushes make for a downright mesmerizing viewing experience for the COLOR OF POMEGRANATES fanatic.

It’s from the Sayat-Nova Rushes that the 2006 documentary MEMORIES ABOUT SAYAT NOVA was largely comprised. That documentary is contained on a 2018 limited edition UK Blu-Ray, a rival to the aforementioned Criterion release. I have yet to determine which version is “better,” but I say THE COLOR OF POMEGRATES is mandatory viewing in virtually any format, a rare example of a widely acclaimed “masterpiece” that fully merits the term.