It’s an interesting, if little-known, fact that the French essentially invented the concept of organized crime. Lurid pulp-tinged texts like Eugene Sue’s LES MYSTERES DE PARIS (1842-43), Paul Feval’s LES HABITS NOIRS (1863-74) and Gustave le Rouge’s LE MYSTERIEUS DOCTEUR CORNELIUS (1912-13) posited the once-unprecedented existence of “aristocracies of crime” whose tendrils stretched beyond the streets to breach the realms of academia and politics. The film world provided an approximation of those texts in the form of LES VAMPIRES (1915-16), a 10 part, 7 hour serial made by the incomparable Louis Feuillade (1873–1925).

The film world provided an approximation of those texts in the form of LES VAMPIRES (1915-16), a 10 part, 7 hour serial made by the incomparable Louis Feuillade (1873–1925).

LES VAMPIRES’ affinity with the abovementioned texts is evident in the fact that a description by Brian Stableford about LE MYSTERIEUS DOCTEUR CORNELIUS can be applied to LES VAMPIRES, “a narrative in which momentary incidents are far more important than the overarching plot, in which the narrative surge is everything, and the ideative background is only there to provide affective coloration, in the currency of ever-present menace and imminent peril.” Vampires, I should add, don’t actually figure into the saga, but the title nonetheless provides an appropriately macabre frisson.

Vampires, I should add, don’t actually figure into the saga, but the title nonetheless provides an appropriately macabre frisson.

Feuillade made his initial mark in crime cinema with the 1913 FANTOMAS serial. Adapted from the first five novels of that iconic crime series by Marcel Allain and Pierre Souvestre, the FANTOMAS films were, in the words of the poet John Asbury, “More like the books than the books.”

FANTOMAS was also the first major success for Feuillade, who in his lifetime made over 700 films. Of those Feuillade films that are remembered today, nearly all are crime-themed, with LES VAMPIRES, which followed FANTOMAS, being the ultimate example. A heavily improvised swirl of mayhem that admittedly owes something to its predecessor, it is nonetheless distinct enough in all major aspects to be categorized as Feuilladian.

Of those Feuillade films that are remembered today, nearly all are crime-themed, with LES VAMPIRES, which followed FANTOMAS, being the ultimate example.

The situation: ace newspaper reporter Phillippe Guerande (Édouard Mathé) is in pursuit of the Vampires, a criminal outfit who in the first episode kill a prominent police inspector (offscreen) and make off with his head. Where does said head end up? In a hidden compartment in Phillippe’s bedroom wall, of course, which he discovers one night and then immediately goes back to sleep, in a scene so odd and inexplicable I wondered if it was intended as a dream (perhaps it was).

This points to what is, over a hundred years after the fact, LES VAMPIRES’ most enduring element: its surreality. Obviously, there was no such thing as surrealism in 1915-16 (the word was coined in 1917, and the artistic movement it spawned commenced in 1924), yet the surrealists revered Feuillade enormously, and LES VAMPIRES especially. As the surrealist big shots Andre Breton and Louis Aragon said in a joint statement, “there has never been anything more surrealist…than the serial film which not long-ago delighted freethinkers. It is in THE EXPLOITS OF ELAINE and LES VAMPIRES that we will have to look for the great reality of this century, beyond fashion, beyond taste.”

“…there has never been anything more surrealist…than the serial film which not long-ago delighted freethinkers.”

Certainly the Vampires, run by the very Fantomas-like Grand Vampire (Jean Ayme) and the seductive Irma Vep (Musidora)—her name is an anagram, as shown by an animated bit in which the letters literally rise off a poster and rearrange themselves into “Vampire”—behave in ways that seem quite surreal. From hiding a severed head in Jacques’ living room to, in a later episode, using a long pole with a looped rope at its end to literally yank Jacques off his balcony by the neck, these criminals certainly don’t do things the tried-and-true way, and neither do the good guys.

“It is in THE EXPLOITS OF ELAINE and LES VAMPIRES that we will have to look for the great reality of this century, beyond fashion, beyond taste.”

Jacques’ own behavior is just as bizarre and inexplicable as that of the Vampires. His nonchalant reaction to finding the compartment in his wall is especially odd, as is another early scene in which he scales the outer wall of his Parisian house via slats set into the walls, and startles his mother by entering through the fireplace. Normality doesn’t exist in the irrational universe of LES VAMPIRES, and in such an atmosphere narrative disjointedness is not only a preferable choice but, I’d conjecture, a necessary one.

If all this sounds arty or affected, you can rest assured that it plays out in the most overtly commercial, audience-friendly manner imaginable. As Feuillade boasted, “I consider the cinema as a place for rest, cheerfulness, soft emotions, dreams, forgetfulness…I place the public above everything else. Since it is their own aim to be entertained, my only object should be to fulfill their desire. The public is my master.”

LES VAMPIRES is also governed by Feuillade’s ultra-stagey fixed camera compositions. It’s a style that predated the innovations of D.W. Griffith, which Feuillade deliberately ignored throughout his career. He’ll grudgingly provide a close-up on occasion (as in the screen-filling depictions of a deadly needle one of the Vampires fastens to the palm of a hand), but montage is completely absent from the filmmaking palette of LES VAMPIRES.

If all this sounds arty or affected, you can rest assured that it plays out in the most overtly commercial, audience-friendly manner imaginable.

For modern viewers this can make for an annoying viewing experience. The pacing is far slower than what we’ve become accustomed to, with the action sequences confined more often than not to center framed wide shots. Yet the attentive viewer can find much to admire in those shots, such as Feuillade’s ability to make even the most roomy interiors seem claustrophobic, and his ingenious use of profile shots that at times allow us to see into multiple rooms simultaneously.

Further Feuillade trademarks include the rough outlines he drew up in place of traditional scripts, with the actors helping to finalize things on the day of shooting. That improvisatory approach likely explains the actions of the background figures visible in the street scenes, who tend to stare curiously into the camera as the action occurs around them–oblivious, it would seem, to the fact that filming was taking place.

…the background figures visible in the street scenes, who tend to stare curiously into the camera as the action occurs around them—oblivious, it would seem, to the fact that filming was taking place.

Feuillade’s improvisatory shooting style may also explain many of the more inexplicable occurrences in LES VAMPIRES, such as Irma Vep going to work as a maid for Philippe and he not recognizing her (despite having already engaged with her directly), and she later masquerading as a man and, once again, going entirely unrecognized. Irma/Musidora’s finest moment, incidentally, occurs when she dons a skintight black bodysuit and lithely prowls a hotel hallway in episode 6, certainly LES VAMPIRES’ most iconic image.

Musidora, who once stated that “It is vital to be photogenic from head to foot. After that you are allowed to display some measure of talent,” is one element of LES VAMPIRES that hasn’t dated. Her appearance may perhaps be a bit on the chunky side by contemporary standards (especially in contrast to Maggie Cheung and Alicia Vikander, both of whom played the role in modern updatings, and both of whom were as thin as the proverbial rail), but she, with her black ringed eyes and highly emotive performance style, fully retains the mystery and exoticism that made her a popular media figure in the silent era, and the screen’s first true femme fatale.

Musidora, who once stated that “It is vital to be photogenic from head to foot. After that you are allowed to display some measure of talent,” is one element of LES VAMPIRES that hasn’t dated.

Édouard Mathé, by contrast, was and remains quite bland as Phillipe, who may be the protagonist of the early episodes but is (rightly) relegated to a supporting role in the succeeding ones. Specifically, he’s supplanted by his quirkier and more resourceful colleague Oscar Mazamette (Marcel Lévesque) as the Vampires’ chief foil, while the dominating agent becomes Juan-Jose Moreno (Fernand Herrmann), the hypnotically inclined leader of a rival criminal gang who in episode six induces Irma, with whom he’s become besotted, to shoot the Grand Vampire dead.

Tension between Jean Aymé and Feuillade was the alleged culprit for the killing-off, leaving a new, even grander Grand Vampire to assume control on the gang: the heavyset Satanas (Louis Leubas), with whom Moreno joins forces. But then, near the end of episode 8, Satanas meets his end (as Louis Leubas was conscripted to fight in the then-raging Great War) and the Vampires acquire yet another leader: an evil chemist known as Venomos (Frederik Moriss). You can rest assured that the refurbished Vampires get their just desserts in the end—although that end, as we’ll see, is far from final.

The Vampires’ fate also fails to disguise the fact that the film’s true protagonists are not Phillipe or Mazamette but the title characters, and Irma Vep in particular. That was a fact not lost upon French law enforcement, whose upset led to the banning of portions of LES VAMPIRES.

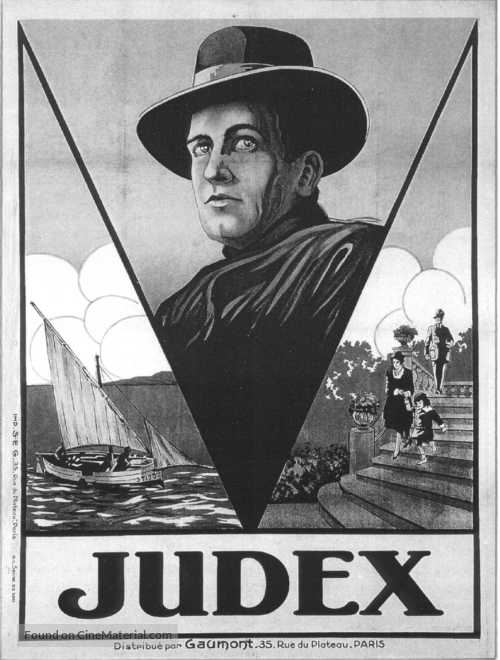

JUDEX (1916) was Feuillade’s apology for that perceived amorality. Consisting of twelve episodes contained in a five-hour runtime, it focused on a caped crimefighter (René Cresté) who prefigured Batman, though without the dark edges that made that character so memorable. Yet JUDEX was Feuillade’s most popular success, and inspired a 1917 sequel, LE NOUVELLE MISSION DE JUDEX, that is said to be “almost unwatchable.”

JUDEX EPISODE 2: L’Expiation (Atonement)

It was followed by TIH MINH (1918), which functioned as a direct sequel to LES VAMPIRES. Its setting is the sunny French Riviera, where the Vampires, looking to avenge their foiling at the end of LES VAMPIRES, set their dastardly sights on the title character, the luscious Eurasian wife (Mary Harald) of a French adventurer (René Cresté, again) who’s just returned from an adventure—and, needless too add, is about to embark on another.

TIH MINH

TIH MINH was succeeded by VENDEMIAIRE (1918), a patriotic war drama that most Feuillade scholars tend to dismiss, and the 12 part BARRABAS (1919), the last of the great Feuillade serials. About a new gang of organized criminals loose in the Riviera, some claim it surpasses LES VAMPIRES. I disagree with that assessment, but will attest that BARRABAS is an exciting entry in Feuillade’s oeuvre.

The same, I’m afraid, cannot be said for Feuillade’s subsequent films. LES DEUX GAMINES (1921), PARISETTE (1921) and VINDICTA (1923) were tearjerkers sorely lacking the surreal brilliance of LES VAMPIRES and its follow-ups, and their poor reception severely damaged their maker’s reputation.

The allure of Feuillade’s finest work, however, never entirely faded. Much of the world experienced a mini-Feuillade boom in the 1960s, starting when Georges Franju released JUDEX (1963), a feature-length remake of Feuillade’s classic serial. Three retro-FANTOMAS films followed (FANTOMAS, FANTOMAS SE DECHAINE and FANTOMAS CONTRE SCOTLAND YARD) during the years 1964-67, as did the enormously popular (in France) TV miniseries LES COMPAGNONS DE BAAL (1968), a direct homage to LES VAMPIRES that was co-scripted by Feuillade’s grandson Jacques Champreux. There was also the premiere release of LES VAMPIRES in the US, occurring in 1965.

That release, which took place in New York City, was in the form of a six hour film without chapter breaks or intertitles, prepared by French Cinémathèque founder Henri Langlois (who quite literally rescued it from the trash), that for decades represented the sole availability of LES VAMPIRES. It wasn’t until the nineties that a proper restoration was undertaken by Jacques Champreux and released to the world, America included.

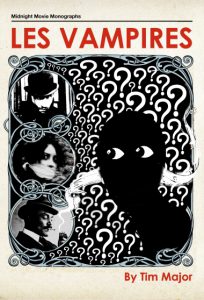

The series was admittedly never too popular here, with non-French textual resources on LES VAMPIRES being extremely slim. Yet a handful of writing exists on the film and Feuillade; I particularly recommend “Maker of Melodrama: Louis Feuillade” by Richard Roud, contained in the November-December 1976 issue of Film Comment, and Tim Major’s 2018 book LES VAMPIRES, from PS Publishing’s Electric Dreamhouse imprint.

The series was admittedly never too popular here, with non-French textual resources on LES VAMPIRES being extremely slim.

As with many Electric Dreamhouse releases, Major’s book is a mixed bag, interspacing witty and perceptive observations about LES VAMPIRES with pointless fictional asides (to remind us that the author is a novelist). Still, the book gets a nod for, if no other reason, being the only English language text devoted to this vital film and, by extension, its creator.

Also worthy of mention are two films by Oliver Assayas. The son of the legendary Jacques Rémy and one of the key French filmmakers to emerge from the 1980s, Assayas has an obsession with LES VAMPIRES that began with the 1996 feature IRMA VEP. A self-consciously hip and undisciplined riff on Feuillade’s themes and imagery, IRMA VEP starred Hong Kong film legend Maggie Cheung, Assayas’ then girlfriend (and future wife), as herself: an HK starlet attempting to navigate the tensions and egos brewing on the set of a French remake of LES VAMPIRES, in which Cheung has been cast as Irma V. What precisely Assayas was attempting to say about Feuillade’s film I don’t know, with Cheung’s appeal, and her unforgettable black latex clad recreation of Musidora’s hotel stalk, being the only things holding this pretentious hodgepodge together.

IRMA VEP 1996

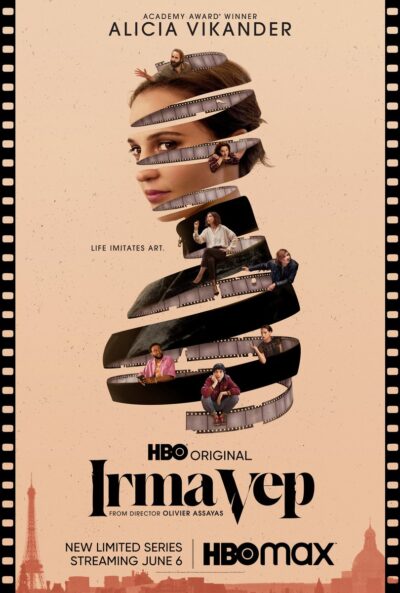

Thankfully Assayas returned to the material with an IRMA VEP TV miniseries that premiered on HBO max in June 2022. Assayas’ mission statement: “Whenever cinema is in chaos, you can do a new IRMA VEP.” Starring Alicia Vikander, relacing Cheung as the actress chosen to play Irma Vep in another LES VAMPIRES remake directed by the same director depicted the earlier film (Vincent Macaigne, replacing Jean-Pierre Léaud). As with Cheung, Vikander finds herself becoming increasingly confused about the boundaries of performance and reality, in what registers as a much better thought out, less affected piece of filmmaking than the feature IRMA VEP, even though the series doesn’t appear to have entirely clicked with audiences.

Assayas’ mission statement: “Whenever cinema is in chaos, you can do a new IRMA VEP.”

IRMA VEP 2022

One imdb user dismissed the new IRMA VEP as “An arrogant series about narcissistic individuals,” and another as a “snooze fest.” I disagree with both assessments (which I say pertain much better to the feature version) but will acknowledge that the series will be incomprehensible to anyone not familiar with LES VAMPIRES, which informs the program in a variety of ways both direct (each episode is named after a portion of Feuillade’s masterpiece) and otherwise.