There’s nothing else quite like EINSTEIN ON THE BEACH. Dubbed by some as (not a joke) “the most revolutionary artistic achievement of the twentieth century,” it’s a staunchly avant-garde opera with the scope of a Broadway spectacular, created by two highly individual multimedia artists: composer Philip Glass and designer Robert Wilson. It premiered in 1976 and has been performed throughout the world in engagements that continue to this day, which brings up EINSTEIN ON THE BEACH’S most noteworthy feature: the fact that it doesn’t appear dated in any respect, feeling every bit as fresh and unprecedented as it likely did when it premiered.

There’s nothing else quite like EINSTEIN ON THE BEACH. Dubbed by some as (not a joke) “the most revolutionary artistic achievement of the twentieth century,” it’s a staunchly avant-garde opera with the scope of a Broadway spectacular, created by two highly individual multimedia artists: composer Philip Glass and designer Robert Wilson. It premiered in 1976 and has been performed throughout the world in engagements that continue to this day, which brings up EINSTEIN ON THE BEACH’S most noteworthy feature: the fact that it doesn’t appear dated in any respect, feeling every bit as fresh and unprecedented as it likely did when it premiered.

Viewing this show is an admittedly demanding experience. Ostensibly about Albert Einstein, it’s nearly five hours long (which is actually fairly short for Wilson, whose productions have been known to run up to twelve hours) and revels in nonlinearity, with Wilson’s formalist bent resulting in elaborate staging and scenery that evince a variety of disparate influences: METROPOLIS, Jean Genet, 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY, the 1960s avant-garde productions of the Living Theater, Carole King (whose tune “I feel the Earth Move” is directly referenced), etc.

Also featured is an electric keyboard dominated score from Philip Glass’s pre-Hollywood period—i.e. before he turned his talents to film scoring in the 1980s onward, which blunted the minimalistic repetition so integral to his approach. The music of EINSTEIN ON THE BEACH is prime Philip Glass, with a bizarre, asynchronous lilt that constantly builds and repeats itself yet never comes to any sort of conventional resolution, and an overtly robotic overlay, presumably to illuminate Albert Einstein’s scientifically-inclined mindset (David J. Skal’s cyber-horror novel ANTIBODIES, about people who long to become machines, contains multiple references to the EINSTEIN ON THE BEACH score).

Other pivotal figures involved in the creation of this mega-production include choreographer Lucinda Childs, whose subtly repetitive dance movements can be viewed as flesh-and-blood manifestations of Glass’s music, and Christopher Knowles, who wrote the libretto. Knowles, an autistic New York City based artist, was a teenager when he created the words for EINSTEIN ON THE BEACH, having been discovered at age thirteen by Wilson. Those words, incidentally, were crafted in response to Wilson asking Knowles his thoughts on Albert Einstein, which yielded the seemingly nonsensical monologues spouted by the performers of EINSTEIN ON THE BEACH, which include verbiage like “it could be a balloon…it could be very fresh and clean…all these are the days my friends and these are the days.”

EINSTEIN ON THE BEACH is one of the few works you can accurately describe as a “meditation on…” without sounding like a pretentious asshole, as a meditation is exactly what it is, on Albert Einstein’s ideas and legacy. His status as the Father of the Atomic Age is of particular interest to Glass and Wilson, as indicated by the last three words of the title (taken from the famous nuclear holocaust themed novel and film ON THE BEACH) and the missile imagery that recurs throughout the program. There’s even a diagram itemizing the potential destruction of a nuclear explosion that’s reflected onto a screen toward the end of the opera, which is the closest the material gets to showing the outcome of Einstein’s dabbling with nuclear power; it is, however, more than enough to make the point.

Also contained in the program are various “knee plays,” so named because they serve as jointed connections between the opera’s four main portions. In these knee plays a pair of robotic women dressed, like nearly everyone in the production, in black pants, suspenders and white shirts repeat the Christopher Knowles penned phrases transcribed above, surrounded by an equally robotic chorus who continually count up to eight (in the history of music no composition outside of “Rock Around the Clock” has ever done more with numbers) and at one point assume teeth brushing motions with toothbrushes, in preparation for a mass recreation of the classic photo of Einstein sticking out his tongue.

Also contained in the program are various “knee plays,” so named because they serve as jointed connections between the opera’s four main portions. In these knee plays a pair of robotic women dressed, like nearly everyone in the production, in black pants, suspenders and white shirts repeat the Christopher Knowles penned phrases transcribed above, surrounded by an equally robotic chorus who continually count up to eight (in the history of music no composition outside of “Rock Around the Clock” has ever done more with numbers) and at one point assume teeth brushing motions with toothbrushes, in preparation for a mass recreation of the classic photo of Einstein sticking out his tongue.

Early on in the opera a young boy stands atop a crane throwing paper airplanes at the performers below. A bit later a surreal courtroom (representing society’s attitude toward Einstein) is presided over by a man and a boy who constantly repeat “this court of common thieves is now in session,” followed by a scene in a prison in which one of the two robot women seen in the Knee Plays lounges on a bed. A train set bit follows, in which a woman shoots a man with pistol, with both performers enacting their roles in extreme slow motion (in a surreal dramatization of the theory of relativity).

One especially striking element is an object identified in the act breakdown as a “Space Machine.” This machine initially takes the form of a long white rectangle hovering around the stage that, in the fabulously mind-blown climax, eventually reveals its interior, which looks like a giant beehive before which people twirl through the air amid floating telephone booths, the Knee Play gals crawling across the stage and a guy doing a dance with two flashlights. Throughout it all a frizzy white-haired violinist—Einstein himself, presumably—sits off to the left side of the stage, taking no evident notice of the surrounding action.

One especially striking element is an object identified in the act breakdown as a “Space Machine.” This machine initially takes the form of a long white rectangle hovering around the stage that, in the fabulously mind-blown climax, eventually reveals its interior, which looks like a giant beehive before which people twirl through the air amid floating telephone booths, the Knee Play gals crawling across the stage and a guy doing a dance with two flashlights. Throughout it all a frizzy white-haired violinist—Einstein himself, presumably—sits off to the left side of the stage, taking no evident notice of the surrounding action.

I won’t venture to explain any of this, as I have no idea what any of it means, and anyway I’m not sure there is any concrete meaning. Robert Wilson claims that playwright Arthur Miller once summed up his feelings about EINSTEIN ON THE BEACH with the words “you know, I don’t get it,” to which Wilson allegedly replied, “you know, I don’t get it either.”

If the info contained in Glass’ 2016 memoir WORDS WITHOUT PICTURES is to be believed, much of EINSTEIN ON THE BEACH came about due to chance and circumstance. The counting motif, for instance, apparently originated by having the singers utilize the solfege system of do, re, mi, fa, so, la, si, albeit with numbers in place of the syllables; Wilson, according to Glass, asked if the numbers were the lyrics and Glass, on a whim, answered yes. A similarly laissez-faire aesthetic seems to have gone into the choreography of the performers, particularly an odd hand gesture they all make that comes, according to Wilson, from the fact that in photos Einstein always held his fingers in a certain way.

Yet the show exerts a definite fascination, and held my attention through virtually the entirety of its highly expansive  runtime (the dance sequences aside, whose inclusion I’ve frankly never understood). Wilson has a David Lynchian talent for creating images that make an indelible impression on the subconscious, from the woman who continually walks forward and backward across the stage with one arm constantly outstretched to emphasize something we can’t see, to those floating telephone booths we can see in the psychedelic climax. Glass’s music has a similar effect, the vocal chorus in particular, which stands as one of his finest and most altogether bizarre musical feats.

runtime (the dance sequences aside, whose inclusion I’ve frankly never understood). Wilson has a David Lynchian talent for creating images that make an indelible impression on the subconscious, from the woman who continually walks forward and backward across the stage with one arm constantly outstretched to emphasize something we can’t see, to those floating telephone booths we can see in the psychedelic climax. Glass’s music has a similar effect, the vocal chorus in particular, which stands as one of his finest and most altogether bizarre musical feats.

EINSTEIN ON THE BEACH premiered at France’s Avignon Festival in July 1976, the start of a tour that came to encompass Italy, Germany and the United States, with Lucinda Childs playing one of the main female roles (and winning an Obie Award for it) and Robert Wilson performing the aforementioned flashlight dance. The show, following an attempted 1990s film adaptation by the British filmmaker director Peter Greenaway (the helmer of a 1983 TV documentary on Glass) that never got off the ground, has gone through numerous alterations at the hands of various directors. The most interesting of them would appear to be an installation-styled reinterpretation staged in Berlin by director Berthold Schneider and designer Veronika White in 2001 and ‘05, in which spectators were allowed to directly interact with Robert Wilson’s scenery while the performers emoted on video screens.

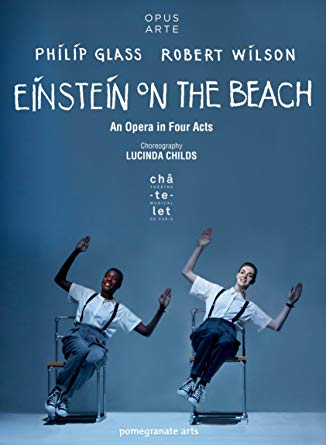

The program’s second major tour occurred in 2012-15, and began in March, 2012 at the Opera Berlioz in Montpierre, France (with actress Kate Moran effectively taking over the role originated by Lucinda Childs). It was on this second tour that the sole video recordings of EINSTEIN ON THE BEACH were created, in Paris’ Théâtre du Châtelet on January 7, 2014. The first of those recordings was a live broadcast courtesy of France’s Thema, which presented it, in the manner of most televised operas, in the multi-camera style of a football game. The second and more resonant recording, released on DVD and Blu-Ray in 2016, was taken from the same performance and features a similar multi-camera visualization, but is more thoughtfully edited. It certainly makes for quite a contrast with most filmed opera performances, which tend toward the classical and traditional, two things EINSTEIN ON THE BEACH definitely isn’t.

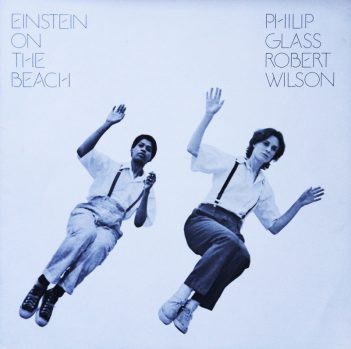

The other major EINSTEIN ON THE BEACH media artifacts are the various CD recordings of Philip Glass’s score. That score was released in a variety of abridged formats, including a few brief selections included on the 1989 album SONGS FROM THE TRILOGY—so named because Glass considers EINSTEIN ON THE BEACH part of a trilogy of operas centered on famous figures who effected change through non-violent means. The others are 1979’s SATYAGRAHA (about Gandhi), and 1983’s AKHENATEN (about the Egyptian pharaoh Akhenaten). EINSTEIN ON THE BEACH can safely be crowned the highlight of the trilogy, and perhaps of Glass’s entire career  (it’s certainly far superior to his trilogy of operas inspired by the Jean Cocteau films ORPHÉE, LA BELLE ET LA BÊTE and LES ENFANTS TERRIBLES, the last two of which played in LA in the nineties, and to these eyes added up to very little).

(it’s certainly far superior to his trilogy of operas inspired by the Jean Cocteau films ORPHÉE, LA BELLE ET LA BÊTE and LES ENFANTS TERRIBLES, the last two of which played in LA in the nineties, and to these eyes added up to very little).

I’d like very much to offer some recommendations of plays or operas similar to EINSTEIN ON THE BEACH, but frankly I’m having trouble coming up with any. The Living Theater production of FRANKENSTEIN, a black and white recording of which was made in the 1960s, has a similarly freeform gist (but is far less effective overall), while the Philip Glass scored science fiction themed opera 1000 AIRPLANES ON THE ROOF is nearly as fine (but lacks the scope and audacity), with EINSTEIN ON THE BEACH standing by itself as one-of-a-kind, never-to-be-repeated sui generis masterpiece.