In June 2022 CRIMES OF THE FUTURE, the first feature in eight years to be directed by David Cronenberg—and the first in 21 years to emerge from an original Cronenberg screenplay—was released. That release followed a contentious Cannes screening, which garnered a six-minute standing ovation and also a lot of reported walk-outs. Critical reception has likewise been mixed, with some reviewers praising the film to the skies and others decrying it for being “too gross.”

In June 2022 CRIMES OF THE FUTURE, the first feature in eight years to be directed by David Cronenberg—and the first in 21 years to emerge from an original Cronenberg screenplay—was released. That release followed a contentious Cannes screening, which garnered a six-minute standing ovation and also a lot of reported walk-outs. Critical reception has likewise been mixed, with some reviewers praising the film to the skies and others decrying it for being “too gross.”

As for myself, I had an altogether different reaction to CRIMES OF THE FUTURE. I agree the film, a quintessentially Cronenbergian science fiction nightmare, was plenty gross, with graphic depictions of organ removal, bodily mutilation (self and otherwise) and skull drilling, yet what struck me the most was its overall form. In contrast to previous Cronenberg freak-outs like SHIVERS, SCANNERS and THE FLY, CRIMES is quite cerebral in tone and content, with a narrative that is, first and foremost, extremely talky.

Talk is essential to this film. Cronenberg has worked with playwrights (such as David Henry Huang and Christopher Hampton) in the past, but CRIMES OF THE FUTURE is the most overtly theatrical of his films. There’s a reason for that: the many audacious concepts it introduces—such as a future world in which humans have lost the ability to feel pain, a biomechanical form of machinery, a performance artist who grows mutant innards to be surgically removed for adoring audiences, a government agency devoted to registering errant organs and an evolutionary quirk that has turned certain people into plastic-eating freaks—need to be explained to audiences, requiring the use of what are known in movie circles as exposition dumps (interestingly enough, the one thing that isn’t explained is precisely how this bizarre future came to be—a nuclear war? Disease? Technology run amok?).

Science fiction-horror films have been stymied with the exposition—or exposition dump—issue from time immemorial. It’s something that may work fine in literary form—with the UK’s Ian Watson having made a career out of writing science fiction novels (such as THE EMBEDDING, THE JONAH KIT and ORGASMACHINE) that function as grab-bags of interesting ideas that all require copious explanation—but not necessarily in cinematic terms. It’s hardly incidental that as of 2022 none of Watson’s novels have been adapted for the screen.

CRIMES OF THE FUTURE is not unlike a Watson narrative in its conglomeration of mind-tugging concepts presented via a plethora of learned explanations. The characters in this film spend a lot of time explaining things, a surprise given that Cronenberg’s 1996 adaptation of J.G. Ballard’s CRASH was noteworthy for largely dispensing with the philosophical musings that powered the novel (“The crash between our two cars was a model of some ultimate and yet undreamt sexual union. The injuries of still-to-be-admitted patients beckoned to me, an immense encyclopedia of accessible dreams”), with its narrative related in the form of imagery at once clinical and seductive.

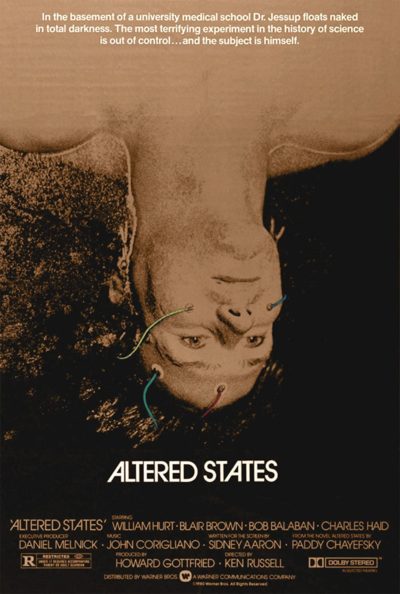

Another explanation-heavy science fiction drama is the Paddy Chayefsky scripted, Ken Russell directed ALTERED STATES (1980). It is, again, a film whose far-out conceptions, which include a scientist (William Hurt) reducing himself to a simian state via an isolation tank and later regressing back to the initial moment of creation, require explanation, which Chayefsky provides in extremely verbose blocks of dialogue (“The final truth of all things is that there is no final Truth. Truth is what’s transitory. It’s human life that is real”).

What’s most interesting about the film is the manner in which Russell films that dialogue: in kinetically worded (the actors all talk very fast), motion heavy scenes that occur more often than not on stairs or amid furious pacing. Some have claimed that Russell was looking to sabotage the screenplay (that was the view of Chayefsky, who removed his name from the film), others that he was simply trying to render uncinematic material cinematic. ALTERED STATES’ style has, in any event, been replicated in many subsequent films—JACOB’S LADDER (1990) bears its unmistakable influence—and proven itself a classic of sorts (with ALTERED STATES also serving as the title of the American printing of Russell’s 1991 autobiography).

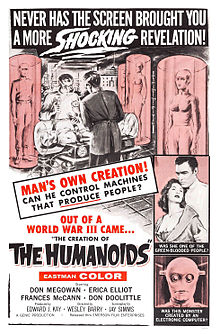

An example of the opposite approach can be found in the grade-z sci fi programmer THE CREATION OF THE HUMANOIDS (1962), from former child actor turned B-movie impresario Wesley Barry. Based on the 1948 novel THE HUMANOIDS by Jack Williamson, it’s an action-free, talk-heavy futuristic drama that, in the words of one critic, “tackles BLADE RUNNER’S themes with a $1.98 budget.” Barry’s approach is extremely concept-driven (if I didn’t already know better I’d opine that Ian Watson worked on the screenplay), consisting of portentous monologues captured in lengthy takes via an unmoving camera. The result is certainly not without interest, but watching it takes a fair amount of patience.

Regarding the abovementioned BLADE RUNNER (1982), that Ridley Scott directed classic offers yet another way of rendering a concept-heavy science fiction narrative in cinematic terms. In adapting Philip K. Dick’s 1968 novel DO ANDROIDS DREAM OF ELECTRIC SHEEP?, Scott and screenwriters Hampton Fancher and David Webb Peoples expended the majority of their energy on creating a future Los Angeles, with the novel’s philosophical core muted severely. That’s a good thing, because the film reverses Dick’s set-up about humanoid robots loose in an underpopulated future world; in such a landscape, in which non-mechanized life is regarded as precious, it makes sense that authorities would administer elaborate psychological tests to sort the human from the non-human. The movie, however,  takes place in an overpopulated future in which the androids, or replicants, fit right in with all the weirdos and miscreants peopling this world. But again, Scott’s fabulously immersive visual landscape is its own reward.

takes place in an overpopulated future in which the androids, or replicants, fit right in with all the weirdos and miscreants peopling this world. But again, Scott’s fabulously immersive visual landscape is its own reward.

Of those three films CRIMES OF THE FUTURE is closest to THE CREATION OF THE HUMANOIDS. As in it, CRIMES’ fascination is (the grossness aside) entirely conceptual. That’s not an inherently bad thing, and CRIMES OF THE FUTURE is not a bad movie. It’s visually enticing, with painterly cinematography by Douglas Koch and a Greek island setting whose run-down and decayed aspects are highlit by Cronenberg and Koch (it’s a definite step up from the nondescript big city landscape described in Cronenberg’s initial early-00s screenplay, entitled PAINKILLERS). Plus the acting, by Cronenberg regulars Viggo Mortensen and Don McKellar, and newcomers to the fold like Léa Seydoux, Kristen Stewart and Scott Speedman, is uniformly top-notch; this is a skilled cast whose efforts helps render Cronenberg’s futuristic netherworld concrete and palatable. Even all the overheated exposition has its place, provided one is of the right orientation; CRIMES OF THE FUTURE is truly (as was said about the 1990 blab fest MINDWALK) a film for passionate thinkers. Still, I’d have preferred some Ken Russell kineticism mixed in, spiced with the visual immersion of Ridley Scott.