Having explored the careers of so many accomplished filmmakers, here I’ll take a look at one who has not lived up to his full potential. That filmmaker is England’s Chris Cunningham, an irrepressible artiste with a profoundly dark yet undeniably evocative sensibility. I don’t think the term genius (novelist William Gibson’s word for Cunningham) is out of place here–and nor, unfortunately, is wasted capability.

Having explored the careers of so many accomplished filmmakers, here I’ll take a look at one who has not lived up to his full potential. That filmmaker is England’s Chris Cunningham, an irrepressible artiste with a profoundly dark yet undeniably evocative sensibility. I don’t think the term genius (novelist William Gibson’s word for Cunningham) is out of place here–and nor, unfortunately, is wasted capability.

Chris Cunningham started out making conceptual designs for filmmakers like Richard Stanley, Clive Barker and David Fincher. Cunningham’s work on 1995’s JUDGE DREDD brought him, at age 23, to the attention of Stanley Kubrick, who tapped Cunningham to work on A.I. (whose eventual director Steven Spielberg rejected Cunningham’s services, instead going the safe and familiar route with Stan Winston). From there Cunningham segued into directing music videos, which cemented his fame.

Chris Cunningham started out making conceptual designs for filmmakers like Richard Stanley, Clive Barker and David Fincher. Cunningham’s work on 1995’s JUDGE DREDD brought him, at age 23, to the attention of Stanley Kubrick, who tapped Cunningham to work on A.I. (whose eventual director Steven Spielberg rejected Cunningham’s services, instead going the safe and familiar route with Stan Winston). From there Cunningham segued into directing music videos, which cemented his fame.

The two dozen or so videos Cunningham directed in 1996-99 remain some of the most iconic examples of the form, showcasing a vision as masterly and distinct as that of just about any other filmmaker you can name. Highlights include Aphex Twin’s “Come to Daddy,” whose images of rubber-faced children corralled by an emaciated mutant were unprecedented back in ‘96; Portishead’s “Only You,” with its mind-tugging depictions of underwater people composited into an urban Hellscape; Squarepusher’s “Come on My Selector,” with its 3 minute prologue involving a girl breaking out of an insane asylum by impersonating a grown-up with a dog’s head; Aphex Twin’s “Flex,” a 17 minute mini-film depicting naked bodies assuming tortured contortions over dark backgrounds; and Bjork’s “All is Full of Love,” Cunningham’s crowning achievement as far as I’m concerned, a darkly gorgeous vision of cybernetic romance that, in keeping with most of Cunningham’s work, is technically impeccable in every respect.

The two dozen or so videos Cunningham directed in 1996-99 remain some of the most iconic examples of the form, showcasing a vision as masterly and distinct as that of just about any other filmmaker you can name. Highlights include Aphex Twin’s “Come to Daddy,” whose images of rubber-faced children corralled by an emaciated mutant were unprecedented back in ‘96; Portishead’s “Only You,” with its mind-tugging depictions of underwater people composited into an urban Hellscape; Squarepusher’s “Come on My Selector,” with its 3 minute prologue involving a girl breaking out of an insane asylum by impersonating a grown-up with a dog’s head; Aphex Twin’s “Flex,” a 17 minute mini-film depicting naked bodies assuming tortured contortions over dark backgrounds; and Bjork’s “All is Full of Love,” Cunningham’s crowning achievement as far as I’m concerned, a darkly gorgeous vision of cybernetic romance that, in keeping with most of Cunningham’s work, is technically impeccable in every respect.

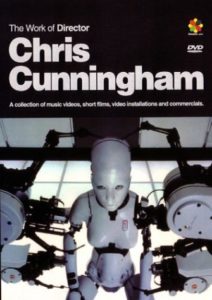

Nearly all of the above are featured on the WORKS OF DIRECTOR CHRIS CUNNINGHAM DVD compilation. Released as part of a “Directors Label” series that included music video compilations by Cunningham’s colleagues Spike Jonze and Michel Gondrey, THE WORK OF DIRECTOR CHRIS CUNNINGHAM is, I’m sorry to report, the most disappointing of the three. Certainly the DVD is worth picking up, but it only features eight of the twenty plus music videos Cunningham had directed at the time (it’s missing essentials like The Auteurs’ “Light Aircraft on Fire”–a clip from which, of a guitar-strumming dog, is seen on the DVD menu–and “Back with the Killer Again,” which features some of the most aggressively disturbing imagery Cunningham has created). Also featured are a handful of Cunningham directed advertisements and , inexplicably enough, an excerpt from “Flex” that only lasts three minutes!

, inexplicably enough, an excerpt from “Flex” that only lasts three minutes!

Like Jonze and Gondrey, it seemed that Chris Cunningham was poised to make the jump to feature filmmaking in the late nineties. Were he to do so I believe he’d give David Lynch a serious run for his money in the realm of subconscious dementia, but that transition never occurred. Cunningham was, however, attached for a time to a proposed feature film adaptation of the Tanino Liberatore Euro comic RANXEROX, and also the long awaited movie version William Gibson’s seminal cyberpunk novel NEUROMANCER. The latter project in particular was highly anticipated, and underwent a reported three year planning period, but ultimately came to naught.

What followed was a dearth of unfinished and never-realized projects. A rare exception was the short film “Rubber Johnny,” released on DVD in 2005. Shot largely through night vision digital video, it’s about a severely deformed kid (played by Cunningham himself) in a dark room, who bops in his wheelchair to electronic music by Aphex Twin while his bewildered dog watches. “Rubber Johnny” has become quite popular on YouTube, but to get the full effect one must peruse the 42 page booklet that came with the DVD (apparently Cunningham’s “first published book of original artwork”), and in particular the scrotum-like appendage on the cover, an image that recurs in various disgusting permutations throughout the booklet, imparting a rather profound vision of biological grotesquerie.

Another Cunningham short film, “Spectral Musicians,” was commissioned by Warp Films in 2005, but currently exists only in a 93 second snippet on Vimeo and YouTube. Those 93 seconds, however, are pretty amazing, showcasing a girl birthing some kind of alien entity in a riot of blood, viscera and harsh jump cuts. More recently Aphex Twin made the claim that Cunningham completed a “zombie film” (short? feature length?) but elected not to release it.

Much of the blame for Cunningham’s lack of productivity must be placed at the feet of an increasingly conservative, risk-averse industry. I suspect Cunningham would have fit in well with the so-called “Easy Riders, Raging Bulls” generation of the 1970s, and also, perhaps, the independent filmmaking cabal of the early 1990s. Both, unfortunately, were out of vogue by the time Cunningham came into his own as a filmmaker.

Much of the blame for Cunningham’s lack of productivity must be placed at the feet of an increasingly conservative, risk-averse industry. I suspect Cunningham would have fit in well with the so-called “Easy Riders, Raging Bulls” generation of the 1970s, and also, perhaps, the independent filmmaking cabal of the early 1990s. Both, unfortunately, were out of vogue by the time Cunningham came into his own as a filmmaker.

Of course, Chris Cunningham’s own wildly mercurial personality and evident lack of motivation must also be taken into account. According to author Arlen Price, “When the heart is willing, it will find a thousand ways. When it is unwilling, it will find a thousand excuses.” Chris Cunningham may not have that many excuses for his stagnation, but he has offered quite a few, ranging from the claim that he hasn’t come across an ideal feature film project (“I haven’t yet found a story that checks all the boxes in all the things I’m interested in and is strong enough to hold an hour and a half”) to his distress over his legions of imitators (“I got so depressed because my style had become so ubiquitous and it made me lose confidence because everything looked like what I was doing”) to the prevalence of YouTube (“Why spend three years on a short film for it to end up being shown out-of-sync on a shitty format?”).

“Why spend three years on a short film for it to end up being shown out-of-sync on a shitty format?”

In recent years Cunningham has turned out a few advertisements–his 2008 Donna Summer scored spot for Gucci garnered a fair amount of attention–as well as CHRIS CUNNINGHAM LIVE, a 55 minute audio visual program comprised largely of previously shot material. In short, Cunningham is essentially giving us more of the same.

As for the long-form career-defining masterpiece Cunningham appears to have been building toward–be it a video installation, feature film, or even the complete version of “Spectral Musicians”–I’m not holding out much hope. Certainly what Chris Cunningham has provided thus far is impressive, but I for one can’t help but think he has far more to offer.

As for the long-form career-defining masterpiece Cunningham appears to have been building toward–be it a video installation, feature film, or even the complete version of “Spectral Musicians”–I’m not holding out much hope. Certainly what Chris Cunningham has provided thus far is impressive, but I for one can’t help but think he has far more to offer.