It’s a fact that much of the world’s most vital televised science fiction emerges from outside the US. I’ve nothing against STAR TREK, LOST IN SPACE or V, but I say the UK’s THE PRISONER outdoes them all, and while the sci fi themed Hungarian telefilms of András Rajnai don’t quite outdo much of anything (Rajnai’s films are admittedly something of an acquired taste), they do register as intriguing products of a cultural sensibility far removed from our own. Hungarian small screen sci-fi, FYI, is one of the categories I’ll be covering here.

Outside Rajnai’s telefilms, which included POKOL-INFERNO (1974), THE ORCHID CAGE (1976) and DIAMOND PYRAMID (1985), Hungary hasn’t had much of a science fiction scene. Yet the Hungarian sci-fi that does exist is mostly worthwhile, as proven by the work of Péter Zsoldos (1930-1997), who remains best known for his 1971 novel A FELADAT (THE MISSION), which was adapted into a three-part 1975 miniseries that remains a highlight of Eastern Bloc TV.

A FELADAT

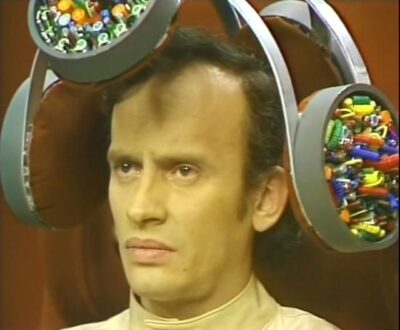

If you can forgive the ultra-tacky seventies-centric set design (which makes the famously threadbare STAR TREK bridge set look positively high-tech) you’ll find in A FELADAT a supremely intelligent and imaginative piece of science fiction. The whole thing is quite cerebral and talk-heavy in its approach, which will doubtless turn off many viewers, but for those of us unafraid of complex thought A FELADAT is compulsive viewing.

It takes place aboard a spaceship docked on an Earth-like planet whose humanoid natives are stuck in an early stage of evolution. The spaceship’s inhabitants, on hand to observe the natives, are all killed in a radiation leak, but the philosophically oriented Gill (Tamas Fodor) manages to survive long enough to set up an automated system that a century later (after the radiation has subsided) implants his personality into the head of a primitive man named Umu.

Possessed of Gill’s thoughts, Umu becomes determined to continue the spaceship’s mission, and to that end downloads Gill’s essence into several of his fellows. This, however, has unintended side effects, with the men’s barbaric natures rising to the fore and leading to all sorts of trouble, including murder. Umu-Gill decides to scour the planet for more evolved inhabitants, which he finds in the form of an isolated tribe of semi-intelligent humans, but implanting Gill’s thoughts into these folk proves quite problematic, and results in some catastrophic upheavals.

The idea of modern humans confronting Neanderthals is a popular one in science fiction, but this is the most vigorous and exhaustive treatment of the concept that I’ve ever encountered. One has to be forgiving of the dated visuals and not-always-plausible narrative (the film spans a period of 200 years, during which time the spaceship where most of the action occurs stays in remarkably pristine condition), but it’s one of the very few examples of televised sci-fi that comes close to approaching the brainy charge of the best science fiction literature. Also, you Pink Floyd fans will recognize the (unauthorized, I’m sure!) instrumental drops from “Have a Cigar” that play over the end credits of each episode.

Another nation that isn’t known for science fiction is Norway. Its primary source for sci-fi literature were the novels of Jon Bing and Tor Åge Bringsværd, or “Bing & Bringsværd,” which included several stories and plays devoted to the crew of the spaceship Marco Polo. The MP was also the subject of the three-part TV miniseries BLINDPASSASJER (STOWAWAY) in 1978 (and continued to be mined in the years following its airing).

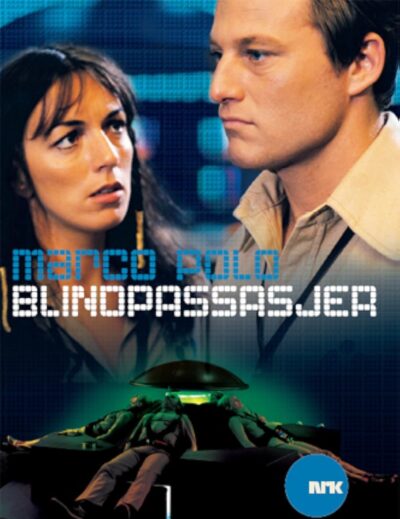

BLINDPASSASJER

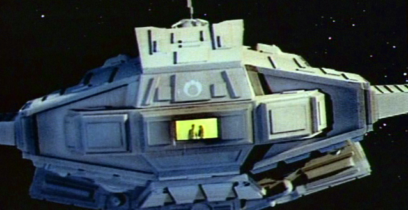

This series has many similarities to A FELADAT, and many of the same annoyances, namely cut rate production design and special effects to match (which in all fairness probably looked much better in 1978). Science fiction tends to date quicker and more dramatically than perhaps any other genre, but an intelligent treatment goes a long way toward maintaining a sci-fi narrative’s relevance, as proven by METROPOLIS (1927) and FORBIDDEN PLANET (1956), two films that look mighty stodgy by modern standards but still retain their initial allure. The same is true of BLINDPASSASJER, which isn’t quite as strong as A FELADAT but makes a sizeable impression.

The setting is the aforementioned Marco Polo, a spaceship on its way back from a research mission on the distant planet Rossum. While the crewmembers are in supervised hibernation shenanigans occur, as evidenced by a busted surveillance camera and video of a humanoid figure materializing in the storage room. It seems a “Biomate,” or artificial human, is aboard the ship, and has taken the place of one of the crewmembers.

Around this time a foreign spaceship is discovered orbiting the Marco Polo. A search of the rogue ship turns up several dead crewmembers who apparently emerged from the surface of Rossum, which is now peopled entirely by robots. The planet’s human colonizers, it transpires, created the robots to help maintain an ecological balance, only to lose control and end up being exterminated by their own non-human creations, with the rogue spaceship representing a doomed attempt by the last surviving humans to flee the robots’ dominion. Now the ‘bots have unleashed the homicidal Biomate aboard the Marco Polo, resulting in suspicion and paranoia, and a bout of uncontrollable lust, among the crew.

As with A FELADAT, BLINDPASSAJER is extremely dialogue heavy. Detailed exposition is required to advance the narrative, resulting in a great deal of plot-based chatter. What’s missing is the complex and distinct character detail of the earlier series, with the human protagonists of BLINDPASSASJER on hand merely to advance the narrative and explain its mechanics.

What gives the series its distinction is the conceptual brilliance of Bing & Bringsværd. Thematically speaking this is an impressive program, with enough invention to pack an entire season of STAR TREK and an old-fashioned storytelling ingenuity that consistently maintains viewer attention. It’s smart, certainly, and imaginative to a fault, but ultimately BLINDPASSASJER triumphs because it’s fun, pure and simple.