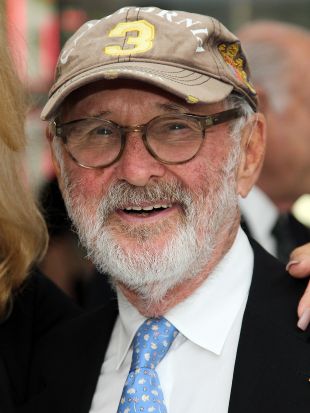

“Canada’s greatest director?” That’s what many would have you believe about the late Norman Jewison. I’m afraid I don’t concur, but am an admirer of Jewison’s talent, and his accomplishment of something most Canadian filmmakers desire but few attain: he made films that “play in the states” and climbed the Hollywood ladder, an achievement in which only one other Canuck director, the Ontario born James Cameron, can be said to have bested Jewison.

But then again, Jewison may be ahead of Cameron in the lexicon of successful Canadian filmmakers, at least on his home turf. Having spent time in Canadian filmmaking circles, I can report that seemingly everyone therein has a Norman Jewison story, if not several (filmmaker Bruce McDonald has been known to frequently namedrop Jewison, as has the Vancouver-based no budget auteur Jack Darcus). He served as a nexus of sorts for Canuck filmmakers, and remained a staunch champion of the scene even after absconding for Hollywood (unlike Cameron, who tends to keep his citizenship on a need-to-know basis), having facilitated the creation of the Canadian Film Centre (CFC) in 1986.

As a director Jewison’s major attribute was his range. His films included the satiric THE RUSSIANS ARE COMING, THE RUSSIANS ARE COMING (1966), THE THOMAS CROWN AFFAIR (1968), a sleek thriller, ROLLERBALL (1975), a CLOCKWORK ORANGE inspired sci-fi shocker (featuring intense depictions of violence that were considered groundbreaking), FIDDLER ON THE ROOF (1971) and JESUS CHRIST SUPERSTAR (1973), stage-based musicals both, the romantic comedies MOONSTRUCK (1987) and ONLY YOU (1994), and prestige projects (read: Oscar bait) like IN THE HEAT OF THE NIGHT (1967), A SOLDIER’S STORY (1984) and AGNES OF GOD (1985).

FIDDLER ON THE ROOF Trailer

IN THE HEAT OF THE NIGHT Trailer

The latter orientation emerged from Jewison’s deeply-held political beliefs (I think you can guess which side he favored) and the fact that IN THE HEAT OF THE NIGHT, which Jewison claimed was personally championed by Senator Robert F. Kennedy, scored so many Oscar nominations (16 to be exact, with 5 wins). That tendency didn’t always result in worthwhile films, alas. In fact, I’d argue that Oscar chasing had a most unfortunate effect on the latter portion of Jewison’s career, which was cluttered with lumbering prestige-fests like THE HURRICANE (1999) and THE STATEMENT (2003) (fun fact: one of Jewison’s Oscar-baiters, the 1989 Warner Bros. production IN COUNTRY, was directly responsible for the success of the same studio’s DRIVING MISS DAISY, a low budgeter slated for a February 1990 release that was moved up and given an Oscar push after Jewison’s film, which was supposed to be Warner’s major ‘89 awards contender, flopped).

DRIVING MISS DAISY Trailer

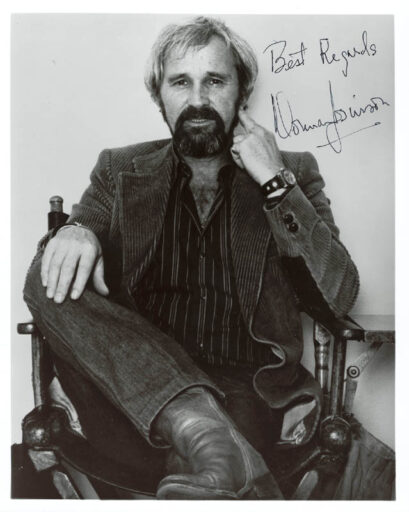

For a full recounting of Jewison’s thoughts and attitudes, read his 2004 memoir THIS TERRIBLE BUSINESS HAS BEEN GOOD TO ME. It proved he was quite the raconteur, offering up many wonderful stories culled from four decades of work in the “Terrible Business” of making movies. The book overall is a warm yet frank and tough-minded read, relating how Jewison began his career directing live television in his native country, and later the US, where he worked with luminaries like Harry Belafonte, Judy Garland and Frank Sinatra.

We also learn that Steve McQueen was selfish, that a drunken John Wayne once called Jewison a “Pinko,” that he immersed himself in Jewish lore to make FIDDLER ON THE ROOF (despite his last name the man wasn’t actually Jewish) and that he suffered a supremely egomaniacal Sly Stallone on F.I.S.T. (1978). Jewison also offers the observation that, regarding Hollywood’s current output, “They’re movies made to appeal to eight to twelve-year-old males and their adult equivalents: guys who have chosen not to grow up,” and claimed, upon losing the best director Oscar for FIDDLER to William Friedkin, “I knew in my heart that FIDDLER would become a classic and remain on the screens of the world and in people’s minds long after THE FRENCH CONNECTION had faded away.” In fact, the opposite has come to pass.

But getting back to the main subject of this essay—Jewison’s Canadian-ness—he admits in his book to doing something unheard-of among Canadian expats: he moved back to his native land after years of living in the US. He was greeted, he claims, by an incredulous immigration officer who asked “Why the Hell are coming back here?” (Fun fact: Jewison eventually returned to the US, and was living in Los Angeles at the time of his January 20, 2024 demise.)

Other noteworthy Jewison endeavors include executive producing the Bruce McDonald comedy DANCE ME OUTSIDE (1994) and its spinoff series THE REZ (1996). I say he should have produced more films by other directors (Jewison’s producer credits include John Irvin’s DOGS OF WAR, Fred Schepisi’s ICEMAN and Pat O’Connor’s JANUARY MAN), especially given the mentorship role he played to so many Canadian cineastes. Had he expanded his producer credits we might have been spared misfires like the deadening Burt Reynolds-Goldie Hawn vehicle BEST FRIENDS (1982) and the misconceived Gerard Depardieu kid movie BOGUS (1996). Luckily Jewison also made some good films, and led a life that’s worth recounting.