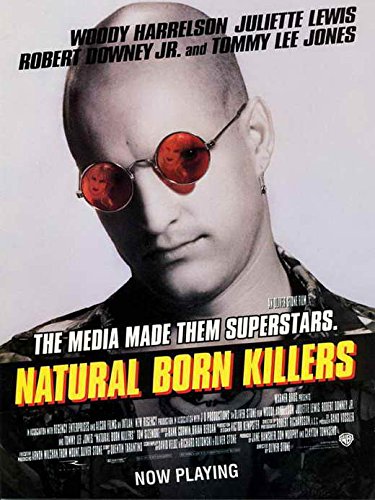

Oliver Stone’s NATURAL BORN KILLERS was the most controversial film of the 1990s. These days NBK is admittedly quite dated in most respects, but the trouble it caused is virtually without parallel. Now that the dust has finally settled, let’s take a look back at this unforgettable film on its fifteen year anniversary.

I feel NBK is a remarkable piece of work, certainly among Oliver Stone’s finest-ever films. Its tripped-out mix of styles and genres within a crazed music video inspired framework remains dazzling, even if it isn’t terribly unique these days. Keep in mind, though, that when NBK first appeared in 1994 there was nothing else like it, and quite a few similarly styled films (FIGHT CLUB, THE MANSON FAMILY, DOMINO) have followed its lead.

NATURAL BORN KILLERS began life as a screenplay by Quentin Tarantino. Penned before Tarantino hit it big with RESERVOIR DOGS, it focused on Mickey and Mallory, a white trash serial killer duo who become media darlings. It was a brilliant script in many respects, thought not so brilliant in others. Tarantino’s unmistakable brand of comedic pop culture inflected dialogue is in full evidence, in a framework that’s both enjoyable and profoundly disturbing in its celebration of two undeniably cool but just as undeniably psychotic murderers.

But NBK, consisting almost entirely of a faux documentary on Mickey and Mallory intercut with dramatizations of M&M’s past exploits, is also the stagiest of Tarantino’s scripts. It was intended as a no-budget indie, which is painfully evident at several points, notably a climactic prison riot conveyed (clumsily) via shadows on a wall and a trickle of blood. In adapting that script, Oliver Stone opened it up and broadened it out considerably. Stone retained Tarantino’s satirical tone and most of his dialogue, but added much of his own, including a first act that filled us in on Mickey and Mallory’s early years and a profoundly nasty scene involving a woman tortured to death in a hotel room. Stone also kept the script’s most memorable sequence, in which Mickey stabs a young woman to death in a courtroom while Mallory cheers him on, though it survives on film (with Ashley Judd proving quite memorable as the undeserving victim) only as a DVD extra.

Tarantino didn’t exactly greet the film with open arms. He was never too copacetic with Stone’s take on the material, which in true Oliver Stone fashion included a lengthy speech about the inherent destructiveness of mankind and an Indian sequence. According to co-producer Jane Hamsher (in her 1997 book on the making of the film), Tarantino opposed the project long before Stone became involved, and tried to sabotage it on at least one occasion. Tarantino and Stone remained at odds throughout the remainder of the decade, and Tarantino even physically attacked co-producer Don Murphy in a Beverly Hills eatery, reportedly over the aforementioned Hamsher book.

Tarantino’s meddling wasn’t the only problem the shoot encountered, as by all reports the production was a drug-fuelled nightmare that resembled the finished film in many respects. Following its release Juliet Lewis went into a California withdrawal treatment center and co-star Robert Downey Jr. had a number of embarrassing substance abuse-related problems. Yet the film that resulted was a wonder, with Stone at his most audacious and Lewis and Woody Harrelson essaying the most electrifying movie serial killer duo this side of Bonnie and Clyde.

Believe it or not, upon its August 1994 release NBK actually received a fairly warm reception. Film Threat and Entertainment Weekly ran lengthy pieces on the film, which also received thumb approval from Siskel and Ebert, and opened number one at the box office.

As a then film student who caught NBK on its opening night, I can attest the film generated a palpable excitement. Quite simply, it stood out: a ferocious, nightmarish psychofest that neatly encapsulated the media landscape of the early nineties (gripped by the O.J. Simpson, Tanya Harding and Lorena Bobbitt scandals, all referenced in NBK) while simultaneously casting a critical eye upon it, all in the context of a terrifically gripping dark comedy. NBK was easily the coolest thing around, at least until Tarantino’s PULP FICTION premiered in October of that same year—and, as I’m sure I don’t need to tell you, single-handedly redefined the filmic landscape.

I’m not going to malign PULP FICTION, as its credentials are pretty inviolable. But while it’s aged better than NBK, I’m not sure I’ve ever considered it superior.

I must have seen both movies at least 5 times apiece theatrically, so they’re essentially neck-and-neck in my eyes. 1994 saw the bows of many memorable films (HEAVENLY CREATURES, ED WOOD, THE SHAWSHANK REDEMPTION), but for me the year will forever be defined cinematically by the unforgettable one-two punch of NATURAL BORN KILLERS and PULP FICTION.

It was around the time of PULP FICTION’S release, however, that the anti-NBK brigade commenced. The fact that Tarantino didn’t like NBK was a big strike against it, with everyone suddenly livid about how Oliver Stone had “screwed up” Sir Tarantino’s apparently immaculate screenplay (I wonder how many of those finger-pointers had actually read that script).

There were also those in the hipster set who resented a Hollywood insider like Stone making a big budget movie that utilized underground film techniques. Those nay-sayers invariably pointed to similarly themed, apparently “better” films like LOVE AND A .45 and I WAS A TEENAGE SERIAL KILLER. Both are solid works, certainly, but in point of fact NBK far outdoes them in every respect.

But the real controversy was still to come. Before the year was done NBK was blamed for inciting seemingly every crime committed around the world, as it would be throughout the remainder of the decade—up to and including the Columbine High School massacre of 1999, whose perpetrators allegedly used the initials NBK as their code.

NBK was the focus of a high-profile 1995 lawsuit (later thrown out of court) that was partially instigated by novelist John Grisham, who claimed the plaintiff, convenience store cashier Patsy Byers, was shot and paralyzed because of the film. Grisham proclaimed that “The last hope of imposing some sense on Hollywood will come through another great American tradition, the lawsuit…It will only take one large verdict against the likes of Oliver Stone, and then the party will be over.”

Oliver Stone was certainly no stranger to controversy, having been widely castigated for MIDNIGHT EXPRESS, BORN ON THE FOURTH OF JULY and JKF, but the fuss over NBK’s supposed criminal influence was without precedent. Never mind that in many cases the movie-murder connection was tenuous at best (i.e. 14-year-old murderer Nathan Martinez stating he wanted to be famous “like the natural born killers,” which was apparently enough to convict the film, or Jeremy Allan Steinke’s admission that he watched NBK before murdering his family in 2006, even though his friends claimed Steinke’s mental stability was in question long before then).

Thus as the nineties wore on, defending NBK wasn’t merely uncool but tantamount to supporting real-life mass murder. That’s despite the fact that the film, to any semi-intelligent viewer, very clearly decried the murderous behavior of its protagonists, and had clear antecedents in A CLOCKWORK ORANGE, BADLANDS and the Tarantino scripted TRUE ROMANCE.

These were things reviewers and politicians initially understood, but apparently forgot later on (see the chapters on the film in Eric Hamburg’s book JFK, NIXON, OLIVER STONE AND ME and the articles “Unnatural Killers” by John Grisham and “Natural Born Copycats” by Xan Brooks). How was it that commentators in 1994 got the joke while those of later years became hung up on the fact that NBK’s protagonists were bad guys who were allowed to get away in the end? I think the answer has as much to do with fundamental changes in the decade as it does with whatever crimes NBK might have “caused.”

The 1990s were an odd time. Today we tend to flash back on grunge culture when the decade is mentioned, but that only held sway in the early to mid nineties. After that the pop culture landscape did an abrupt 180-degree turnabout, with cultural mainstays like Nine Inch Nails, PULP FICTION and Courtney Love replaced by The Spice Girls, SWINGERS and Britney Spears. Grit and edginess gave way to sanitization and predictability, with Adam Sandler elevated from a marginally talented SNL alum to a veritable demi-God and SCREAM “redefining” the horror genre with its shallow teenybopper aesthetic.

In such an atmosphere it made sense that NBK, which fit right in with the year in which it was made, was vilified. Of course the film would likely also have been quickly cast aside (as were so-called envelope pushers like PRIEST, 8MM and THE CELL) were it not for all the furor, which kept NBK in the public eye for years after its release.

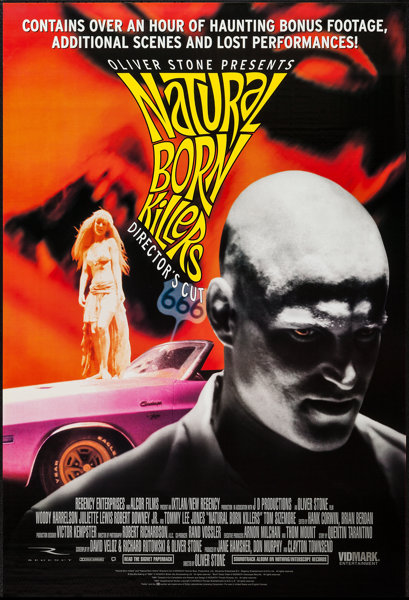

Anti-NBK sentiment was so virulent that Warners scuttled plans to release an unrated director’s cut of the film on video and laser disc (and later DVD). That video ended up released by the independent outfit Trimark, whose out of print DVD and VHS versions for many years represented the sole availability of the director’s cut in the US. While the theatrical cut isn’t entirely without worth (I saw it numerous times, remember), the unrated version represents NBK at its ultimate.

Which brings us up to date. The controversy has died down to the point that you can actually admit to liking NBK without being branded a serial killer sympathizer, and Quentin Tarantino appears to have patched up his differences with Oliver Stone and Don Murphy. NATURAL BORN KILLERS, meanwhile, has been supplanted as the media’s favored whipping boy by the likes of SAW and HOSTEL. But the fact that it managed to freak so many people out for so long is an accomplishment few other films can claim, and proof that, whether you like NATURAL BORN KILLERS or not, there is something to it.