A few years ago I wrote about children’s literature of an especially dark and aberrant nature, as seen in classics of the form like STRUWWELPETER, ANYHOW STORIES and AMPHIGOREY. Here I’ll be revisiting this topic, with mini-reviews of several more scary kids’ books that aren’t as well known as the abovementioned titles but are just as deserving of your attention.

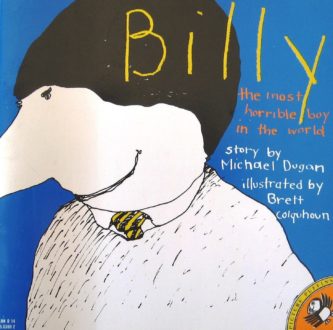

First up is the 1981 Australian import BILLY THE MOST HORRIBLE BOY IN THE WORLD. Written by MICHAEL DUGAN in a succession of short, pointed stanzas, it’s about Billy, who at age two becomes determined to be the “most horrible boy in the world.” He realizes this ambition by committing a variety of anti-social and downright evil acts, such as tampering with a teddy bear he was given “To play with and be friends,” but “He filled it up with gunpowder/Then lit it at both ends.” On Billy’s first day of school “His teacher thought him sweet/Within an hour he’d hanged her/From the rafters by her feet,” and then there’s a portion in which “Billy set his aunt on fire/And screamed with great delight/“Look how Auntie’s burning Dad/It makes the room so bright.””

First up is the 1981 Australian import BILLY THE MOST HORRIBLE BOY IN THE WORLD. Written by MICHAEL DUGAN in a succession of short, pointed stanzas, it’s about Billy, who at age two becomes determined to be the “most horrible boy in the world.” He realizes this ambition by committing a variety of anti-social and downright evil acts, such as tampering with a teddy bear he was given “To play with and be friends,” but “He filled it up with gunpowder/Then lit it at both ends.” On Billy’s first day of school “His teacher thought him sweet/Within an hour he’d hanged her/From the rafters by her feet,” and then there’s a portion in which “Billy set his aunt on fire/And screamed with great delight/“Look how Auntie’s burning Dad/It makes the room so bright.””

For those of you worried that Billy might not get his comeuppance, rest assured that the book is staunchly moral in its outlook, although that morality is strictly of the Old Testament variety. From the final page (!!!SPOILER ALERT!!!): “A boy like Billy couldn’t last/And in his seventh year/The neighbors hung him from a tree/And no one shed a tear.”

Crucial to the book’s effect are the dazzling pen and ink illustrations of BRETT COLQUHOUN. Quite simple in conception yet impressively detailed in execution, Colquhoun’s drawings recall past masters of children’s book art like Edward Gorey and Maurice Sendak, capturing the best elements of both, and perfectly complimenting Michael Dugan’s magnificently vile verse.

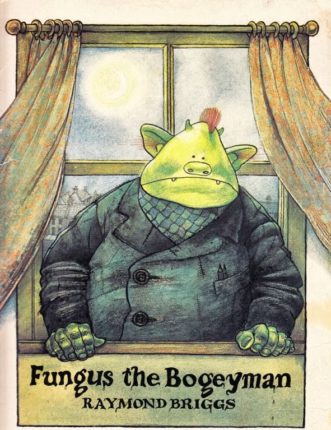

1977’s FUNGUS THE BOOGEYMAN is a 40-page graphic novel that finds England’s RAYMOND BRIGGS (of WHEN THE WIND BLOWS and  numerous other publications) in a particularly ghoulish mood. The book, like most of Briggs’ others, is light and comedic in tone, but has an extremely dank, gruesome core—as Briggs later stated, “For two years I worked on FUNGUS, buried amongst muck, slime and words.” Those things are bequeathed by the fact its main character is, as the title proclaims, a Bogeyman, whose job is to make aboveground peoples’ lives difficult.

numerous other publications) in a particularly ghoulish mood. The book, like most of Briggs’ others, is light and comedic in tone, but has an extremely dank, gruesome core—as Briggs later stated, “For two years I worked on FUNGUS, buried amongst muck, slime and words.” Those things are bequeathed by the fact its main character is, as the title proclaims, a Bogeyman, whose job is to make aboveground peoples’ lives difficult.

Fungus’s duties include making things go bump in the night, pouring soot into chimneys, knocking slates off rooves, etc. During the day Fungus and his fellows reside in subterranean dwellings that are kept suitably damp and sordid so the Bogeys won’t catch a “warm.” The Bogeys prefer “olds” to news, congregate in “Odiums” to experience noxious smells, drink glasses full of slime that come in yellow and green varieties, and speak—and scrawl graffiti—in mournful quotations like “Nothing is permanent but woe” (although apparently “Almost all Bogey quotations are misquoted, as Bogeys hate accuracy”).

It’s all laid out in Raymond Briggs’ inimitable style, which has a somewhat handmade yet also boldly artistic sheen. Unlike so many other modern comic book creators, Briggs accomplished the outlining, coloring, shading and scripting of his book all by himself, and has come up with a thoroughly individual concoction packed with enough detail and inspiration to fill a fantasy trilogy.

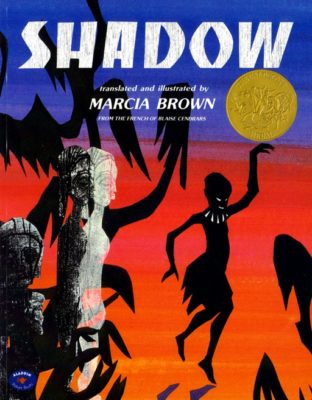

SHADOW (1982) is an illustrated prose poem written by France’s BLAISE CENDRARS (1887-1961) and translated and illustrated by MARCIA BROWN. The subject is Shadow, a spectral personage conjured up by Cendrars’ travels in Africa. Marcia Brown emphasizes those African origins in her illustrations, which are set on desolate plains packed with silhouetted figures. The artwork has a starkness and simplicity that works well with the subject matter, and African culture as a whole.

SHADOW (1982) is an illustrated prose poem written by France’s BLAISE CENDRARS (1887-1961) and translated and illustrated by MARCIA BROWN. The subject is Shadow, a spectral personage conjured up by Cendrars’ travels in Africa. Marcia Brown emphasizes those African origins in her illustrations, which are set on desolate plains packed with silhouetted figures. The artwork has a starkness and simplicity that works well with the subject matter, and African culture as a whole.

As described by Cendrars, Shadow is a mute being who’s quite active at night, when it hangs out in forests and mingles with firelight (but finds its powers considerably reduced in the daytime). It is “the mother of all that crawls, all that squirms,” and must be respected, “for though Shadow has no voice, like the echo, it can cast a spell over you.” Overall this is an extremely slim and frankly pretty scant little volume, but it leaves an undeniably haunting imprint.

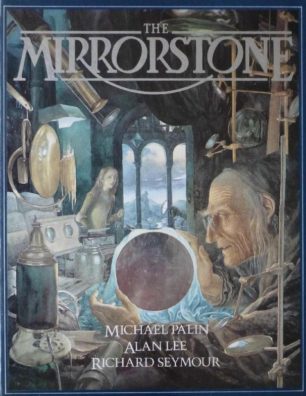

Far more substantial from a narrative standpoint is 1986’s THE MIRRORSTONE, which  provides a heavy dose of no-frills dark fantasy, dreamed up by Monty Python’s MICHAEL PALIN. Palin was the co-writer of Terry Gilliam’s TIME BANDITS, so his facility for fantastic imagination is without question; I just wish the prose were more expressive, as the descriptions Palin provides are disappointingly flavorless and perfunctory. The artwork, at least, by ALAN LEE, is quite sumptuous, and worth perusing on its own.

provides a heavy dose of no-frills dark fantasy, dreamed up by Monty Python’s MICHAEL PALIN. Palin was the co-writer of Terry Gilliam’s TIME BANDITS, so his facility for fantastic imagination is without question; I just wish the prose were more expressive, as the descriptions Palin provides are disappointingly flavorless and perfunctory. The artwork, at least, by ALAN LEE, is quite sumptuous, and worth perusing on its own.

The story involves a young boy thrust into a medieval fantasy world after seeing a strange face staring back at him from his bathroom mirror. In this other world the boy meets an old man who wants him to find a specially designed mirror that was lost years earlier. Tracking down the Mirrorstone involves an immersion in a vast underwater kingdom, a confrontation with a Cthulhu-like monstrosity and a brief imprisonment inside a crystal ball, culminating in (of course) a happy ending.

Also included are several hologram images of a type that were all the rage among publishers in the mid-eighties (holograms, as you may recall, graced quite a few Zebra book covers), but in these pages never seem like anything more than precisely what they always were: a hollow and rather pointless gimmick.

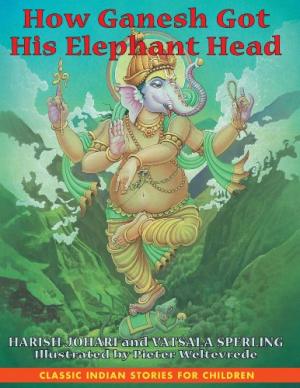

It’s a sad fact that we in the western world have had our folklore sanitized and sugar-coated over the centuries, so I guess it makes sense that other cultures are due the same treatment. Case in point: 2003’s HOW GANESH GOT HIS ELEPHANT HEAD, which tells the story of the elephant-headed god Ganesh, a mainstay of Hindu folklore. Authored by HARISH JOHARI and VATSALA SPERLING, the book is part of a series called “Classic Indian Stories for Children,” and the fact that it’s aimed as youngsters explains why the story has been sanitized considerably, and also the concluding “Note to Parents and Teachers” that spells out the tale’s “enduring truths.”

It’s a sad fact that we in the western world have had our folklore sanitized and sugar-coated over the centuries, so I guess it makes sense that other cultures are due the same treatment. Case in point: 2003’s HOW GANESH GOT HIS ELEPHANT HEAD, which tells the story of the elephant-headed god Ganesh, a mainstay of Hindu folklore. Authored by HARISH JOHARI and VATSALA SPERLING, the book is part of a series called “Classic Indian Stories for Children,” and the fact that it’s aimed as youngsters explains why the story has been sanitized considerably, and also the concluding “Note to Parents and Teachers” that spells out the tale’s “enduring truths.”

Yet those things don’t negate the starkness of the story, which even in its present watered-down form involves jealousy, revenge, mass warfare, animal cruelty and a double decapitation. Of course, Johari and Sperling do their best to blunt the rougher edges, as when Lord Vishnu, the god of preservation, asks a mother elephant’s permission before chopping off her child’s head so it can be placed on the beheaded Ganesh’s shoulders (whereas in the tale’s initial form Vishnu isn’t nearly as nice). The artwork by PIETER WELTEVREDE is quite strong and culturally specific, created through age-old methods of classical Indian painting (involving dousing the canvas with water on numerous occasions).

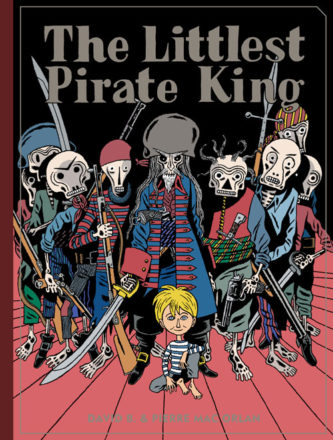

Closing out this overview on a high note, THE LITTLEST PIRATE KING (2009) is a prime example of the French “La bande dessinee,” i.e. children’s  comics—although I’m not sure how kid friendly this profoundly bleak, melancholy little book truly is. Written by the renowned poet/novelist PIERRE MAC ORLAN and illustrated by the great DAVID B. (of the ground-breaking grown-up graphic novel EPILEPTIC), it deals with some pretty weighty themes—mainly the inevitability of death and its effects on the living.

comics—although I’m not sure how kid friendly this profoundly bleak, melancholy little book truly is. Written by the renowned poet/novelist PIERRE MAC ORLAN and illustrated by the great DAVID B. (of the ground-breaking grown-up graphic novel EPILEPTIC), it deals with some pretty weighty themes—mainly the inevitability of death and its effects on the living.

A band of undead pirates are cursed by God to sail monster-filled seas, and wreak the anger and resentment engendered by their condition upon the living. Their most fervent wish is to get a hold of a living child so they can torture it, a wish that is unexpectedly granted when a massive ship explodes in front of them and yields up a surviving infant boy. As the kid grows, however, the pirates find themselves forming a bond with him, and by extension a newfound respect for human life, while the boy in turn becomes increasingly besotted with death. This is a conflict with no easy solutions, and to their credit David B. and Pierre Mac Orlan don’t offer any.

David B.’s loopy and flamboyant art is an undoubted highlight, offering up striking images of the undead pirates’ ship surrounded by sea monsters and, in the book’s most maniacally inspired bit, a riot of mutated animal-faced people (representing how the pirates view the living). Such thematically complex dementia is in my experience almost unheard-of in children’s literature (English language children’s literature, that is!), making this publication, courtesy of translator Kim Thompson and Fantagraphics Books, a most welcome acquisition for those who prefer their kid lit above and beyond.