Here we have a new batch of Illustrated Oddments, books that in their unfathomable oddness deserve “some ink on this site, even if I (for whatever reason) can’t really justify writing full reviews.” So said I in the first ILLUSTRATED ODDMENTS overview, which is furthered below.

Here we have a new batch of Illustrated Oddments, books that in their unfathomable oddness deserve “some ink on this site, even if I (for whatever reason) can’t really justify writing full reviews.” So said I in the first ILLUSTRATED ODDMENTS overview, which is furthered below.

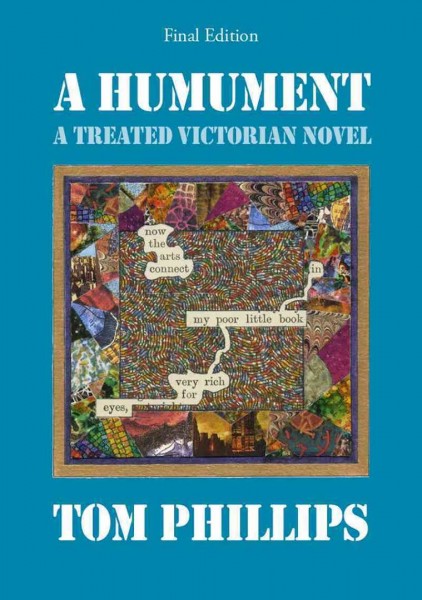

First up: A HUMUMENT, a “treated” Victorian text from 1980 (several revised versions have followed). The instigator was the British artist, historian and filmmaker TOM PHILLIPS, who took the long-forgotten 1892 novel A HUMAN DOCUMENT (or A HUMAN DOCUMENT) and decorated each page in his own inscrutable, yet extremely eye catching and artistic, manner. If this sounds familiar it should, as a similar method was utilized by Brion Gysin and William S. Burroughs in their famed “cut up” experiments, and also in the books of Crispin Hellion Glover (such as RAT CATCHING and OAK-MOT), who was very likely familiar with A HUMUMENT.

Unfortunately Tom Phillips lacks the demented ingenuity of Messrs. Gysin, Burroughs and Glover, turning out a tome that to these eyes appeared like a child’s defacement of a school textbook. Each page is “treated” in a different way, with every word crossed out on one and the entirety of the text painted over but for a few choice words on a subsequent page, while on another wavy lines deface the text, and so forth. I’m told this book has been eagerly dissected by many an art student over the years, and it is undeniably pretty to look at, but I got very little out of A HUMUMENT.

another wavy lines deface the text, and so forth. I’m told this book has been eagerly dissected by many an art student over the years, and it is undeniably pretty to look at, but I got very little out of A HUMUMENT.

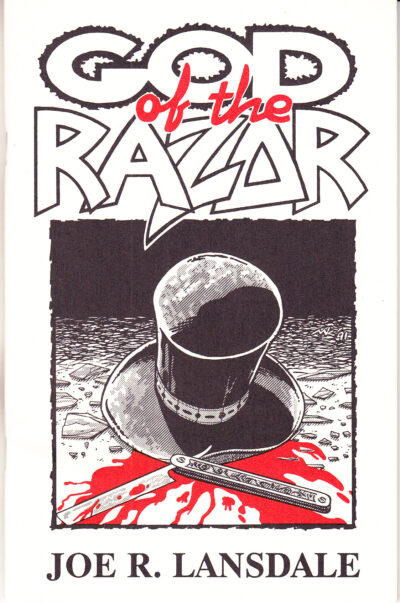

GOD OF THE RAZOR is a limited edition chapbook from Crossroads Press that’s roughly thirty pages long. It’s JOE LANSDALE’s 1992 reflection on his self-created God of the Razor (separate from his 2007 take in the more substantial Subterranean Press volume THE GOD OF THE RAZOR), featuring an essay on the rocky publishing history of the novel THE NIGHTRUNNERS (in which GotR debuted), followed by the “God of the Razor” short story. Most interestingly, there are several pages’ worth of artistic renderings of the character, who sports a mouthful of razor-sharp fangs, wields an imposing straight razor, wears a top hat on its head and sports decapitated human heads in place of shoes.

The artists are an impressive line-up: A.C. Farley, Timothy Truman, Mark Masztal, Michael Zulli, Mark Nelson, Stephen R. Bissette, Elman Brown and S. Clay Wilson. Of the interpretations, Michael Zulli’s authentically nightmarish depiction of a maniacally grinning spot lit figure,  silhouetted over an abstract background, stands out, as does Elman Brown’s magisterial Bernie Wrightson-esque drawing of a musclebound monstrosity, while S. Clay Wilson’s crazed, detail-heavy take is quintessentially Wilson-esque (which is to say: for grown-ups only).

silhouetted over an abstract background, stands out, as does Elman Brown’s magisterial Bernie Wrightson-esque drawing of a musclebound monstrosity, while S. Clay Wilson’s crazed, detail-heavy take is quintessentially Wilson-esque (which is to say: for grown-ups only).

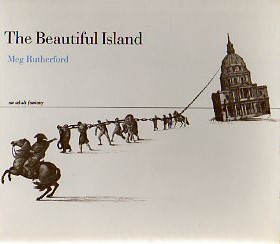

THE BEAUTIFUL ISLAND, an “Adult Fantasy” by the Australian sculptor MEG RUTHERFORD, hails from 1969. It’s example of collage art of a type popularized by Max Ernst, but with a narrative (of sorts). It concerns a beautiful island to which several opulent buildings are laboriously transferred by rope, ship and hot air balloon; not all the structures survive the journey, but those that do are rewarded with “sunshine and peace,” while their human inhabitants experience “dancing and happiness and joy without end.” There’s just one problem: most of the buildings end up situated upside-down.

The narrative, conveyed in short, terse sentences (each of which fills an entire page), isn’t much. The artwork, however, is pretty seamless, with the Rutherford created collages appearing organic and unaffected (i.e. not at all like the cut and paste configurations they are), regardless of how bizarre the imagery becomes.

regardless of how bizarre the imagery becomes.

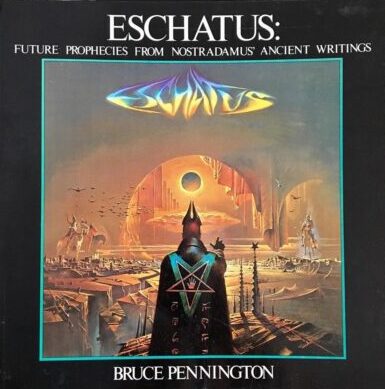

ESCHATUS: FUTURE PROPHECIES FROM NOSTRADAMUS’ ANCIENT WRITINGS (1976-77) is a large format paperback by BRUCE PENNINGTON. Pennington is a veteran science fiction book cover illustrator, which is evident in the paintings that pack ESCHATUS, which purports to illustrate the CENTURIES—or prophecies—drafted in 1555 by the French seer Nostradamus. Pennington, as he makes sure to enumerate in his introduction, insists on translating those prophecies in their original, highly esoteric form, without the tacked-on modern interpretations (such as the replacement of the word “Hister” with “Hitler”) that deface most contemporary Nostradamus translations.

Pennington situates his drawings in a very particular future era, which he identifies as “Europe during the two hundred years from the start of the twenty-second century up until the years just prior to the “Great Millennium,” at the beginning of the twenty-fourth century.” Minutely drafted disasters are common, with meteor strikes, massive conflagrations and desiccated wastelands occurring in strange neo-pagan landscapes packed with mythological beings and UFOs. The  kinship of these drawings to Nostradamus’ prophecies is questionable (I’m not sure precisely what the sentence “An adventurer with a twisted tongue Will come of the gods the sanctuary” has to do with Pennington’s interpretation, consisting of a flying saucer perched on a mountaintop), with the book existing as a curiosity above all else.

kinship of these drawings to Nostradamus’ prophecies is questionable (I’m not sure precisely what the sentence “An adventurer with a twisted tongue Will come of the gods the sanctuary” has to do with Pennington’s interpretation, consisting of a flying saucer perched on a mountaintop), with the book existing as a curiosity above all else.

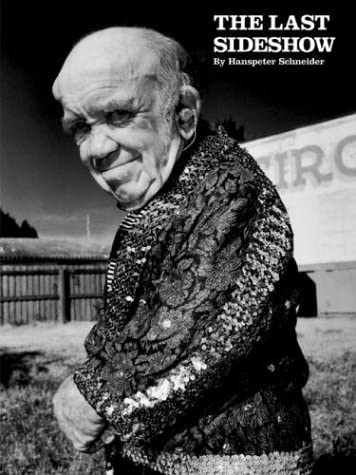

THE LAST SIDESHOW (2004) may seem like an exercise in photographic surrealism, with black and white photographs by the German fashion photographer HANSPETER SCHNEIDER held together by esoteric quotations like “Show business is not like showbusiness. It’s a way of life.” Eventually, though (at the end of the book, to be exact), the truth is revealed: THE LAST SIDESHOW is actually a companion-piece to the 2001 documentary GIBTOWN, from which the quotes were taken.

Depicted is the tiny Florida community of Gibsonton, which is populated entirely by circus performers. There’s nothing in this book that isn’t contained in GIBTOWN (which offers far more in the way of context), but Schneider’s Diane Arbus-like photographic portraits of Gibsonton’s unique residents, situated amid placid yet grungy surroundings (as one of the quotes states, “Gibsonton is the only town where it’s a status symbol to see how much junk you can put in your front yard”), are gorgeous, making one lament that more fashion photographers don’t expend their energies on circus performers.

don’t expend their energies on circus performers.

ROARR CALDER’S CIRCUS (1991) by MAIRA KALMAN consists of photos, taken by DONATELLA BRUN, of the miniature circuses that were created by the late Alexander Calder (1898-1976) out of household materials. The Kalman scripted text, which has a tendency to loop and zigzag all over the page (in an effort to render it more interesting), is negligible, but the photographic imagery, taken from the Calder collection at NYC’s Whitney Museum of Modern Art, is dazzling. Silhouetted over featureless black backgrounds, we’re shown indistinct wire figures, a scarecrow cowboy, a Maharajah with an axe perpetually poised to drop on its head, a mustachioed sword swallower and many more wondrous figures. A children’s book, allegedly, but I doubt too many kids will get much out of ROARR CALDER’S CIRCUS.