Looking back on the many misspent hours of 1980s TV watching, I find that a few (only a few) programs have stuck in my mind. Having already profiled a number of eighties television shows both good and not-so, here I’ll take a look at six episodes of otherwise unremarkable TV series. The following aren’t always “good” by any means, but do have elements to recommend them.

The earliest example I can think of is “He Was Only Twelve,” a 1982 episode of LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE. I know I’m not alone among Gen-Xers in stating that I was practically raised on LITTLE HOUSE. This dopey series, based on the popular YA book series by Laura Ingalls Wilder, was created by the late Michael Landon, and lasted, somehow, for nine seasons. It purported to relate the travails of a family living in America’s heartland during the late 1800s, despite having been filmed in Southern California and utilizing scripts that tended to be recycled from BONANZA.

The earliest example I can think of is “He Was Only Twelve,” a 1982 episode of LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE. I know I’m not alone among Gen-Xers in stating that I was practically raised on LITTLE HOUSE. This dopey series, based on the popular YA book series by Laura Ingalls Wilder, was created by the late Michael Landon, and lasted, somehow, for nine seasons. It purported to relate the travails of a family living in America’s heartland during the late 1800s, despite having been filmed in Southern California and utilizing scripts that tended to be recycled from BONANZA.

“He Was Only Twelve” was a two-parter that served as the season finale of series eight (and in essence the series finale, as season nine was retitled LITTLE HOUSE: A NEW BEGINNING, with much of the original cast phased out). Landon was the writer and director of this mess, which can be viewed as the point at which LITTLE HOUSE truly jumped the shark.

Jumping the Shark, for those who don’t know, refers to a late season episode of HAPPY DAYS in which Fonzie (Henry Winkler) jumped over a shark on water skis, after which, according to media commentator Jon Hein, the program lost its mojo—hence the term “Jump the Shark.” To be sure, there exist plenty of ridiculous late period LITTLE HOUSE episodes to choose from (such as “Come Let Us Reason Together” from season 7, in which twins are birthed whose parents hail from different religious backgrounds, resulting in one of the kids being raised Christian and the other Jewish), but I say “He Was Only Twelve” is the obvious pick.

The episode’s first part was, like quite a few LITTLE HOUSE episodes, a thinly disguised rewrite of a BONANZA script (“He Was Only Seven” from 1972). It featured James (eighties show killer Jason Bateman, whose final LITTLE HOUSE appearance this was), the adopted son of Charles Ingalls (Landon), getting shot upon walking in on a bank robbery, leading to Charles and pal Mr. Edwards  (Victor French) tracking the robbers down and beating ‘em up. It’s in part two, which diverts mightily from the BONANZA storyline, where things get nutty.

(Victor French) tracking the robbers down and beating ‘em up. It’s in part two, which diverts mightily from the BONANZA storyline, where things get nutty.

Completely ignoring the naturalistic bent of the series, and the fact that its protagonist was Charles’ daughter Laura (Melissa Gilbert), Charles takes center stage in his quest for a miracle. James, it seems, survived the shooting but is in a coma, leading Charles to tote him out to what looks like (and very likely was) a park in Simi Valley, where Charles, inspired by a Biblical verse, builds a shrine. He’s visited by an emissary for the Big G (Don Beddoe), who also turns up to warn Charles’s relatives not to join him and James at the shrine and interrupt the coming miracle (which kinda goes against the spirit of family and togetherness the show purported to celebrate)—which when it finally occurs is a bit of a disappointment, consisting of lightning striking the shrine and bringing James back to life. As far as miracles go that’s not very impressive, while as far as LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE goes, “He was Only Twelve” is fascinatingly incongruous.

FRAGGLE ROCK was a Jim Henson kids’ series that was, like all Henson’s non-Muppet Show related projects, problematic. About a race of odd-looking puppet critters living in a cheap-looking underground society, it was never very exciting or enchanting, suffering from cut-rate production values, unmemorable characters and crummy music numbers, three or four of which were crammed into  each episode.

each episode.

The sole FRAGGLE ROCK episode that sticks in my mind is “The Terrible Tunnel,” from the show’s first season. It was intended as a Halloween episode but broadcast in February 1983. Given the off-putting character design and forbidding underground setting, a scary FRAGGLE ROCK episode makes sense. So too the concept of a tunnel that appears amid the rocky Fraggle-scape and sucks up anyone in its path, returning them to the mortal plain as ghosts. The concept is promising, but the writers do very little with it; they have one of the Fraggles, Wembley, stumble upon the tunnel and escape its pull, and then spend much of the rest of the episode trying to convince his fellows of what he saw. Eventually they join Wembley on an expedition to the tunnel, and manage to escape being sucked in, leaving Wembley to conclude that “next time I’ll know better.”

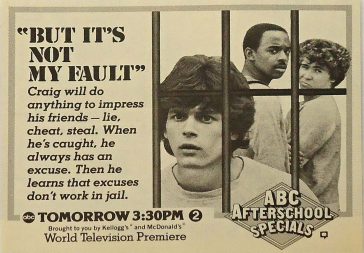

As far as I can recall, I’ve only ever viewed one episode of ABC’S much-despised AFTERSCHOOL SPECIALS. These afternoon  programs existed to teach kids Valuable Life Lessons in the form of cautionary mini-movies, many of which starred familiar faces from the worlds of film and television (Jodie Foster, Laura Dern and Rob Lowe were all AFTERSCHOOL alums). The one I have in mind, “But it’s Not My Fault!,” was broadcast in 1983 as part of the show’s 11th season.

programs existed to teach kids Valuable Life Lessons in the form of cautionary mini-movies, many of which starred familiar faces from the worlds of film and television (Jodie Foster, Laura Dern and Rob Lowe were all AFTERSCHOOL alums). The one I have in mind, “But it’s Not My Fault!,” was broadcast in 1983 as part of the show’s 11th season.

It starred future BAYWATCH and SOCIETY star Billy Warlock as a punk who gets into trouble at the Rolling Hills Mall (back when it was an indoor establishment) and injures an old lady. He’s sent to juvenile hall, the sordid details of which are portrayed with quite graphic-for-1980s-daytime-TV vividness (the body cavity search scene made a particular impression on me). How this episode contrasts with other AFTERSCHOOL SPECIALS I have no idea, but I do know that it scared the Hell out of my ten-year-old self, so I guess it succeeded in its aims.

The appeal of SILVER SPOONS, a 1980s sitcom, was in its presentation of the richer-than-rich existence led by its young protagonist Rickie (Rickie Schroeder). There was more to it, of course, including an eccentric father (Joel Higgins) and grandfather (John Houseman), an alluring mother figure (Erin Gray), and appearances by Alfonso Ribeiro and (again) Jason Bateman as Ricky’s troublemaking pals, but it was the opulence that made it fun, with rich people innovations like a train that runs through “the Ricker’s” house, a phone that quacks like a duck and a computer on which you can create nifty images (i.e. an early eighties variant on Photoshop).

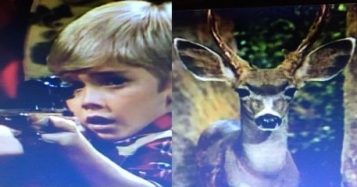

“A Hunting We Will Go” was the sixteenth episode of SILVER SPOONS’S second season. Broadcast in 1984, it was a “Special Episode” of a type that turned up in quite a few eighties sitcoms: a serious one organized around an Important Subject (think of the infamous child molestation/abduction themed DIFF’RENT STROKES episodes, or FAMILY TIES’ “A, My Name is Alex,” in which Michael J. Fox essentially reenacted OUR TOWN). We know this because it begins with Higgins delivering an on-camera warning  that the following may be upsetting to young children, and that we’d best view it “as a family.”

that the following may be upsetting to young children, and that we’d best view it “as a family.”

It involves a hunting trip taken by the Ricker and his elders that concludes with Ricky shooting a deer. The presentation of the deer’s slow death far outdoes BAMBI in awfulness (an end credits voice-over informs us that the deer, contrary to what’s shown, was not harmed), and inspires the guys to swear off hunting forever—although in real life Rick Schroeder apparently went on to become quite an enthusiastic hunter (go figure).

GIMME A BREAK! offered a novel twist on the beloved eighties sitcom formula of black kids adopted by white folks. Here it was white kids being cared for by a black woman (Nell Carter), a housekeeper named Nell who doubled as an all-knowing life coach (a bit like Oprah Winfrey before there was Oprah Winfrey).

“Baby of the Family,” from December 1984, was the eleventh episode of the show’s fourth season, being an attempt at eighties-era  racial commentary—meaning it’s something that could never, ever be made today. It has the troublemaking Samantha (Lara Jill Miller), who infamously called Carter the “N” word in the 1981 episode “Samantha Steals A Squad Car,” getting upset that her little brother Joey (Joey Lawrence) is getting too much attention. She takes revenge on Carter by having Joey perform a music number at a church recital whose particulars are foreshadowed by some chatter about Al Jolson early on in the episode.

racial commentary—meaning it’s something that could never, ever be made today. It has the troublemaking Samantha (Lara Jill Miller), who infamously called Carter the “N” word in the 1981 episode “Samantha Steals A Squad Car,” getting upset that her little brother Joey (Joey Lawrence) is getting too much attention. She takes revenge on Carter by having Joey perform a music number at a church recital whose particulars are foreshadowed by some chatter about Al Jolson early on in the episode.

Nell later chews out Samantha for the scheme, claiming she essentially used the N-word. Samantha denies this with the claim “that’s horrible! I’d never say that word!” See the abovementioned reference to “Samantha Steals A Car” for my rejoinder to that. Regarding the episode under discussion, I’d recommend a viewing, if only to see just how much public tastes, and tolerance, have diverged in the years since 1984.

The 1980s incarnation of ALFRED HITCHCOCK PRESENTS yielded up one noteworthy episode in its inaugural 1985 season: “Final Escape,” the only episode of this program I remember (and possibly the only one I bothered to watch). It was a remake of a similarly titled episode of THE ALFRED HITCHOCK HOUR from 1964. The new “Final Escape” actually improves upon its predecessor, cutting its hour-long runtime in half by adroitly condensing and discarding a number of extraneous subplots and, more importantly, switching the gender of the protagonist from male to female, which has the unlikely effect of increasing both the character’s awfulness and the viewer’s sympathy.

Following a colorized introduction by Alfred Hitchcock from his old series involving Hitch and a scantily dressed woman (which has nothing to do with the drama that follows), we’re plunged into the story of an evil woman (Season Hubley) sentenced to prison. The program shows its age in its depiction of a female penitentiary, which is about on the level of CHAINED HEAT (complete with catfights and a lesbian overseer), and in performances that tend toward the histrionic, but as the narrative develops it’s impossible not to be unnerved.

Following a colorized introduction by Alfred Hitchcock from his old series involving Hitch and a scantily dressed woman (which has nothing to do with the drama that follows), we’re plunged into the story of an evil woman (Season Hubley) sentenced to prison. The program shows its age in its depiction of a female penitentiary, which is about on the level of CHAINED HEAT (complete with catfights and a lesbian overseer), and in performances that tend toward the histrionic, but as the narrative develops it’s impossible not to be unnerved.

Desperate to escape her confinement, Hubley befriends the ageing prison mortician (David Roberts). She enlists him in a scheme to shut her up in a coffin with a corpse, which will then be buried in a cemetery outside the prison and dug back up. What could possibly go wrong? I won’t say, but will reveal that this show is probably what initiated my phobia of being buried alive, a phobia that persists to this day.