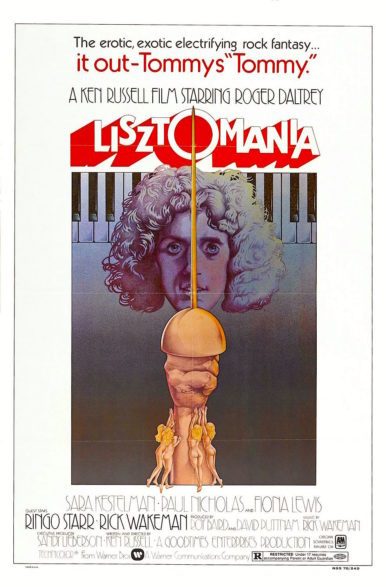

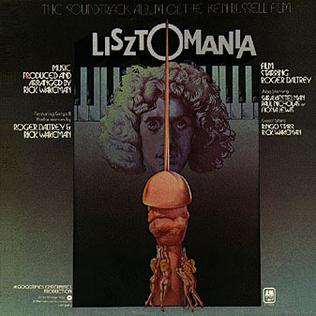

LISZTOMANIA, from writer-director Ken Russell, was released in late 1975. It’s not a widely admired film (to say the least!), but I say it deserves a reappraisal.

LISZTOMANIA, from writer-director Ken Russell, was released in late 1975. It’s not a widely admired film (to say the least!), but I say it deserves a reappraisal.

Trailing Russell’s enormously successful cinematic rock opera TOMMY (with a tagline proclaiming it “out Tommy’s TOMMY”), LISZTOMANIA is by no means the “best” Ken Russell movie; in fact, according to many of the great man’s fans it falls squarely in the opposite category. It is, however, possibly the most Russell-esque of all its creator’s features, being everything one expects from Ken Russell: wild, outrageous and joyously phantasmagoric. As Russell once stated, “in my view, it is far better to OD than to be crippled by restraint,” and restraint has no place in LISZTOMANIA.

“In my view, it is far better to O.D. than to be crippled by restraint”

An ostensible attempt at introducing young audiences to Russell’s career-long obsession with great composers, LISZTOMANIA was the final entry in a loose-knit composer movie trilogy that included THE MUSIC LOVERS (about Tchaikovsky) and MAHLER (about Gustav Mahler). Neither film will ever be mistaken for a Merchant-Ivory production (Russell famously pitched THE MUSIC LOVERS to MGM executives as “a love story between a nymphomaniac and a homosexual”), and neither will LISZTOMANIA. It’s certainly no accident that it marked the end of the trilogy, and also the heyday of Russell’s career, which despite a few high points in the ensuing decade (such as ALTERED STATES and THE LAIR OF THE WHITE WORM) never came close to recapturing the vitality of his early-to-mid 1970s output.

LISZTOMANIA tells (loosely) the story of Franz Liszt, the 19th Century Austrian composer who as depicted by Russell struggled with issues of artistic purity and commercialism. Like Richard Attenborough’s OH, WHAT A LOVELY WAR! (1969), LISZTOMANIA spins a highly symbolic musical fantasy from historical events, with Liszt played by TOMMY’s headliner Roger Daltrey (who sings a handful of Rick Wakeman penned songs, of which the final one, “Peace At Last,” is the most memorable). His colleague and fellow composer Richard Wagner (Paul Nicholas, another TOMMY veteran) is presented as a vampire who sucks Liszt’s blood and creates a literal Frankenstein’s monster in order to overtake Germany. Liszt’s courtship with Princess Carolyn of St. Petersburg (Sarah Kestelman) involves a giant penis bursting out of his pants, drawn inexorably toward a waiting guillotine, while his house is decorated on all sides by giant piano keys and Ringo Starr turns up as the Pope.

Eventually Liszt finds himself locked in an all-out battle with Wagner. Piloting a spaceship powered by the love of his many mistresses, Liszt fires at Wagner, who shoots back with an electric guitar machine gun. He’s no match for Franz Liszt, though, who blows Wagner to bits and flies off into the cosmos singing songs of happiness. Fly on, Liszt!

The madness is enhanced by the wizardly lighting of cinematographer Peter Suschitzky (whose other credits include THE ROCKY HORROR PICTURE SHOW, THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK and CRASH), and the type of headlong energy that illuminates all of Russell’s worthwhile films. The pic is hurt, alas, by performances that aren’t what anyone would call award-worthy. As Liszt Daltrey essentially reprises his role of Tommy the wide-eyed simpleton (one can only imagine what Russell regular Oliver Reed might have done with the role), while Sarah Kestelman, depicted here as a vampish seductress (a la Glenda Jackson in THE MUSIC LOVERS, Tina Turner in TOMMY and Amanda Donohoe in THE LAIR OF THE WHITE WORM), never registers as particularly vampish or seductive.

and CRASH), and the type of headlong energy that illuminates all of Russell’s worthwhile films. The pic is hurt, alas, by performances that aren’t what anyone would call award-worthy. As Liszt Daltrey essentially reprises his role of Tommy the wide-eyed simpleton (one can only imagine what Russell regular Oliver Reed might have done with the role), while Sarah Kestelman, depicted here as a vampish seductress (a la Glenda Jackson in THE MUSIC LOVERS, Tina Turner in TOMMY and Amanda Donohoe in THE LAIR OF THE WHITE WORM), never registers as particularly vampish or seductive.

The film is further afflicted with cheap-looking set design; this, however, actually works in its favor, imparting a hasty and unpolished aesthetic that enhances the sense of frenzied invention. Low budget energy, in other words, is precisely what LISZTOMANIA needs, even though its 1.2 million pound budget wasn’t exactly low.

Critical reaction was about par the course for Russell. That is to say vitriolic, as was evident at a New York press conference recalled by LISZTOMANIA cast member Fiona Lewis, who claims the attendees “were all hysterical, screaming at me things like, ‘How could you make this picture?,’” and in proclamation made the late Evening Standard critic Alexander Walker: “This man must be stopped. Bring me an elephant gun!” (which echoes Pauline Kael’s oft-quoted put-down about THE MUSIC LOVERS: “You really feel you should drive a stake through the heart of the man who made it”).

If LISZTOMANIA resembles anything its Russell’s DANCE OF THE SEVEN VEILS, made five years earlier for the BBC series OMNIBUS. As with LISZTOMANIA, it marked the end of an especially fertile era in Russell’s career, in this case the many 1960s era biopics he made for the BBC (SONG OF SUMMER, DANTE’S INFERNO, ISADORA, ALWAYS ON SUNDAY, etc.). DANCE OF THE SEVEN VEILS was the most notorious of them by far, getting denounced on the floor of Parliament and condemned by the family of composer Richard Strauss, which led to the banishment of all Strauss music on the soundtrack and the near-complete disappearance of the film.

Strauss (played by Christopher Gable) and his alleged ties to the Third Reich were the subjects of DANCE OF THE SEVEN VEILS. That’s depicted via an unfettered music-powered phantasmagoria containing randy nuns, mass carnage and dancing Nazis. Russell claimed it “was meant to work on a deep symbolic level.” Not unlike LISZTOMANIA, which is also foreshadowed in Russell’s defense of the earlier film: “I was guilty only of reflecting on film the elements I found in the music.”

In Russell’s 1989 autobiography A BRITISH PICTURE he dismisses LISZTOMANIA as a “Panavision pop video” (although in later years he came to think better of it). He blames its failure on interference from producer David Putnam (who had worked with Russell far more happily on MAHLER), under whose tutelage “the script became less and less classical–and more and more pop-oriented until it was to Putnam’s satisfaction.” Putnam for his part has a different take, claiming that Russell, apparently the “Most naturally gifted director I’ve ever worked with,” “never  really finished the screenplay and, frankly, he just seemed to go off his rocker.”

really finished the screenplay and, frankly, he just seemed to go off his rocker.”

Who’s right? Both, I’d opine. Putnam is famous for his hands-on approach, both as a producer and a studio head, so the claim that, as one of his colleagues remarked, “Ken got a grip on David and got him to do it his way,” seems a mite farfetched. But then again, Putnam’s account was largely corroborated by Ms. Lewis, who claimed that “The picture got out of control…There was lots of screaming, shouting through bullhorns, and plenty of tears and tantrums.” For that matter, Kathleen Turner, who starred in Russell’s 1984 film CRIMES OF PASSION, tells a similar story, calling Russell a “mad, self-sabotaging genius” and saying of the filming that “As the days went on, things got increasingly out of hand and there was no order.”

What are we to take away from these claims? That, for starters, Ken Russell was a genius, a point on which everyone seems to agree. It’s also evident that he had a bullying streak (of this Paul Sutton’s indispensable survey TALKING ABOUT KEN RUSSELL offers more-than-ample proof), and that he may well have been mad (to further quote Fiona Lewis: “Ken is a very interesting man—and possibly completely insane”), although I’d dispute that assertion.

Russell may have seemed “off his rocker,” but anyone familiar with his nonfiction publications, which include the aforementioned A BRITISH PICTURE (ALTERED STATES in the US), FIRE OVER ENGLAND (THE LION ROARS in the US) and DIRECTING FILMS, will recognize a witty, erudite and altogether sane sensibility. The alleged chaos of his sets is something that’s hardly unprecedented among great filmmakers; as the late actor Victor Argo once said of Abel Ferrara, “I see Abel shooting something and I think ‘What a piece of shit!’ And then I see it on the screen and I say ‘Brilliant! How did that happen?’”

On a related note, feigning insanity to get one’s way was a not-uncommon moviemaker ruse in the 1970s. Directors like Bob Rafelson, William Friedkin, Werner Herzog and Dennis Hopper all used “madness” to their advantage, as did Ken Russell, who may well have been the technique’s supreme master. It helped place him in what Wes Anderson calls “the almost nonexistent category of the movie director who does whatever he wants,” and in the case of LISZTOMANIA I’d say that was a very good thing indeed.