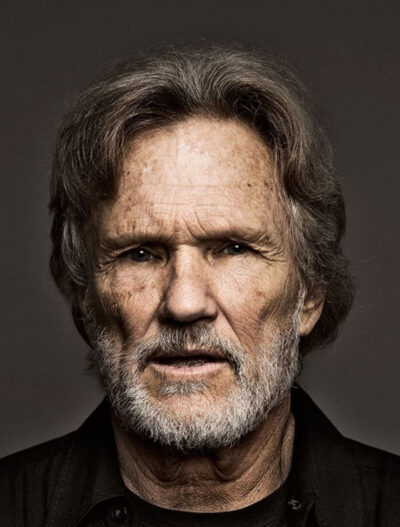

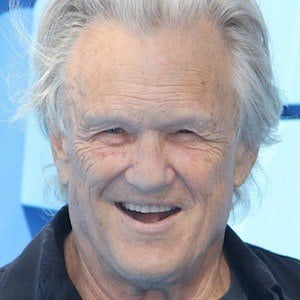

Looking over the imdb page of the recently deceased singer-songwriter-actor Kris Kristofferson, I was astonished to discover a formidable 118 acting credits. I’ve long been convinced that, as with Mick Jagger and David Bowie, singing and songwriting (which yielded iconic tunes like “Sunday Morning Comin’ Down” (see below) and a pre-Janis Joplin “Me and Bobby McGee”) were Kristofferson’s major passions, with acting a mere sideline.

SUNDAY MORNING COMIN’ DOWN (Song)

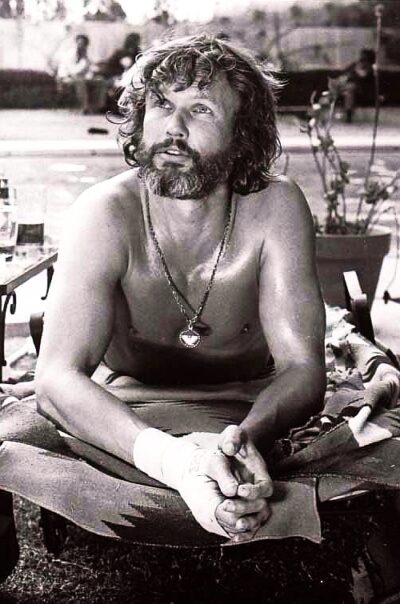

The Texas-bred Kristofferson, after all, tended to be dismissive of a profession he likened to “a nine-to-five job. You do get a certain satisfaction out of it, but you’re reading somebody else’s lines.” That attitude was evident during Kristofferson’s early years in Hollywood, when he famously showed up drunk to an audition for Monte Hellman’s TWO-LANE BLACKTOP, and made his film debut in THE LAST MOVIE (both 1971) solely as a favor to his pal Dennis Hopper.

THE LAST MOVIE (trailer)

The curious thing about the acting of this “walking contradiction” (to borrow a line from one of Kristofferson’s most celebrated tunes) is that, despite a sparse retinue of facial expressions and a limited emotional range, his appearance and mannerisms were quite distinct. Kristofferson certainly benefitted from working with a roster of directors that included Sam Peckinpah, Paul Mazursky, Martin Scorsese, Michael Cimino, Alan Pakula, John Sayles, Tim Burton, Guillermo del Toro and Richard Linklater.

There was also Bill L. Norton, who directed CISCO PIKE (1971), Kristofferson’s second dabbling in film. Playing a reformed drug dealer whose life is thrown into turmoil by crooked cop Gene Hackman, Kristofferson (who admitted that “CISCO PIKE doesn’t prove whether or not I can act”) held his own alongside more talented thespians like Hackman and Harry Dean Stanton. More importantly, Kristofferson’s distant and laconic yet amiable screen persona (think a kinder, gentler Clint Eastwood) was established in CISCO PIKE—not that what he was doing was a straight acting exercise. As Norton said of his leading man, “Kris is the sort of actor whose own character is bigger than the parts he plays.”

CISCO PIKE (Trailer)

Sam Peckinpah, on PAT GARRETT AND BILLY KID (1973), BRING ME THE HEAD OF ALFREDO GARCIA (1974) and CONVOY (1978), essentially shifted Kristofferson around the screen as he saw fit (with Peckinpah’s attitude toward Kristofferson’s Billy the Kid indicated by the fact that his name ranks second in the title). Martin Scorsese, speaking about ALICE DOESN’T LIVE HERE ANYMORE (1974), filmed immediately following PAT GARRETT AND BILLY THE KID, recalls Kristofferson urging “You’ve got to tell me where to stand.”

ALICE DOESN’T LIVE HERE ANYMORE (Trailer)

Speaking of ALICE DOESN’T LIVE HERE ANYMORE, it contains one of Kristofferson’s finest performances. He plays the male love interest of the female lead, a role he replicated nearly as affectingly in Paul Mazursky’s BLUME IN LOVE (1973) and Lewis John Carlino’s British-centric riff on Yukio Mishima’s THE SAILOR WHO FELL FROM GRACE WITH THE SEA (1976)—in which Kristofferson was tasked with epitomizing Mishima’s conception of post-WWII male weakness.

BLUME IN LOVE (Trailer)

It was in ALICE that Kristofferson shone the brightest, precisely because, as in CISCO PIKE, he more-or-less played himself; it’s enough to make one lament that he never worked with Scorsese again (although the latter did pay homage to his former co-star by making Kristofferson’s song “The Pilgrim, Chapter 33,” (below) and accompanying album THE SILVER-TONGUED DEVIL AND I, major plot points in TAXI DRIVER).

THE PILGRIM CHAPTER 33 (Song)

Kristofferson’s multi-film collaborations with talented directors generally yielded positive results. See the two films he made with Alan Rudolph, starting with SONGWRITER (1984), about which I tend to agree with the verdict of its prospective director Ed Zwick: “middle aged, Jewish shit-kicking.” The second of those films, happily, was the altogether superior TROUBLE IN MIND (1985), a sci fi-noir reverie enhanced immeasurably by Kristofferson. Even stronger were his appearances in John Sayles’ LONE STAR (1996) and LIMBO (1999), films that brought out the best in both men (I’ll consciously refrain from mentioning their third collab, the ludicrous 2004 anti-Dubya screed SILVER CITY).

TROUBLE IN MIND (Trailer)

LIMBO (Trailer)

Clearly the quality of Kristofferson’s screen performances were dependent in large part on his directors. It’s no accident that his most memorable acting occurred in the films of great filmmakers, while his work for helmers like Randall Kleiser (on BIG-TOP PEE-WEE), John Maybury (THE JACKET), Ken Kwapis (HE’S JUST NOT THAT INTO YOU) and Albert Pyun (KNIGHTS) was just as you’d expect.

Then there are the outliers, films that despite a combination of promising material and strong directors failed to elicit much from Kristofferson. A great deal has been said (pro and con) about Michael Cimino’s HEAVEN’S GATE (1980), in which Kristofferson, its leading man, gets lost in the scenery. Nor did he distinguish himself in Tim Burton’s 2001 PLANET OF THE APES (a disaster), Guillermo del Toro’s 2002 BLADE II (a decent enough film in which I’m having trouble remembering Kristofferson’s contributions) or Richard Linklater’s 2006 FAST FOOD NATION (likewise).

HEAVEN’S GATE (Trailer)

Ultimately, however, my opinions on Kris Kristofferson’s acting skills and the films in which he appeared are offset by the fact that he managed to maintain his reluctant-thespian status for an amazing five decades—and that, I feel, essentially says all that need be said about Mr. Kristofferson’s eccentric yet highly distinguished acting career.