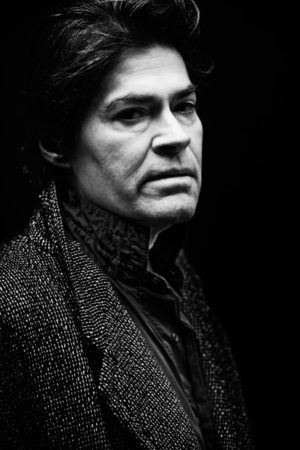

This one hurt. Certainly there have been a lot of famous people deaths that have affected me, but this one impacted me especially. Dallas Mayr, better known to us as Jack Ketchum, was a novelist who during a career that spanned nearly four decades wrote some of the most powerful and disturbing horror fiction in existence. His January 24, 2018 demise was an incalculable loss to the field, and this reader in particular.

This one hurt. Certainly there have been a lot of famous people deaths that have affected me, but this one impacted me especially. Dallas Mayr, better known to us as Jack Ketchum, was a novelist who during a career that spanned nearly four decades wrote some of the most powerful and disturbing horror fiction in existence. His January 24, 2018 demise was an incalculable loss to the field, and this reader in particular.

Ketchum/Mayr’s writing talent was undeniable, and a primary reason I hold him in such high regard. His ultra-spare prose remains unique in and out of the field—he was the undisputed master of the single-sentence paragraph—and that minimalist tendency extends to his narratives. Few of his novels exceed 250 pages, and fewer still can be accused of being overwritten. Furthermore, for all the over-the-top grue for which he’s known, the violence, like most everything else in Ketchum’s fictional universe, is for the most part spare and non-excessive.

I also admire the way Ketchum handled his career: with fortitude, tenacity and a commitment to his own particular vision that’s virtually unheard-of, especially in the horror-sphere. Ketchum wrote exactly what he wanted, never softening the harshness of his prose for the edification of the marketplace nor turning to other, more profitable genres (as so many of his fellow horror scribes did in the nineties) when the horror boom went south. This meant, of course, that Ketchum never attained the fame and fortune of his longtime friend Stephen King, but I don’t think he minded. As Ketchum wrote in his 1997 story “The Work” (about a character who was doubtlessly more than a little autobiographical), “I write what I like to write. The kinds of books I like to read…I’m damned if I’m going to write something just for the money or so some editor can be flavor of the month with the boys on publishers’ row.”

My own history with Ketchum dates back to 1992. It was then that I happened upon a paperback novel called OFFSPRING during a trip to New York. I considered myself then, as I do now, to be pretty knowledgeable about genre fiction, yet here was an intriguing-sounding horror novel written by an author I’d never heard of that purported to be a sequel to a decade old novel—OFF SEASON—that I’d likewise never heard of. I made it a point to track down OFF SEASON and the other four novels—HIDE AND SEEK, COVER, SHE WAKES and THE GIRL NEXT DOOR—Jack Ketchum had published up to that point, a gambit, believe it or not, that was relatively easy and inexpensive (now, of course, those books in their original editions are costly collector’s items).

Truly, here was something altogether unique: a writer of undeniable brilliance, genius even, who nobody seemed to know about but me. Documentation about Ketchum was quite scarce back then, with the only mentions I was able to find being a couple brief write-ups about OFF SEASON in Deep Red magazine, a quote from Ketchum in Tekli-Li! and a mention of OFF SEASON in the “Best of Horror Fiction” listing that concludes Douglas E. Winter’s 1985 volume FACES OF FEAR. How could this be?

Thankfully, Ketchum’s next novel, 1995’s JOYRIDE, featured a lengthy blurb by Stephen King proclaiming that “(Jack Ketchum) has become a cult figure among genre readers and a kind of hero to those of us who write tales of terror and suspense.” Given that Ketchum had been laboring in obscurity for over fifteen years, I really wish King had spoken up a bit earlier. Still, that blurb can be pinpointed as the true start of a phenomenon that should have begun much earlier.

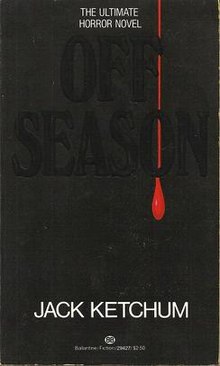

Back in 1981, to be precise, when OFF SEASON was first published. By then Ketchum had already led a pretty varied existence, have spent time as  a hippie, literary agent and freelance journalist, and emerged with a confident and streamlined piece of work that ranks as one of the great debuts in horror novel history. Like all of Ketchum’s early novels, OFF SEASON was a paperback original, and given a very respectable print run by Ballantine, as well as an audacious cover consisting of a drop of blood over an all-black background with the imposing tagline “The Ultimate Horror Novel.”

a hippie, literary agent and freelance journalist, and emerged with a confident and streamlined piece of work that ranks as one of the great debuts in horror novel history. Like all of Ketchum’s early novels, OFF SEASON was a paperback original, and given a very respectable print run by Ballantine, as well as an audacious cover consisting of a drop of blood over an all-black background with the imposing tagline “The Ultimate Horror Novel.”

Admittedly, the plot of OFF SEASON isn’t much, concerning some horny city folk on a stay in the woods in upstate New York who find themselves facing down a band of inbred cannibals. The book’s power is in its details, and the final 100 pages are a minutely described gore fest the likes of which I’ve never encountered anywhere else. Add to that Ketchum’s concise, economical writing style and some extremely well-drawn characters (particularly the cannibals), and you’ve got a true classic for the ages, one that appeals to our basest desires while simultaneously forcing us to seriously examine our reactions to books like this one.

The novel was a success, selling a reported quarter million copies, but it did very little for Ketchum’s profile. Ballantine, it seems, underwent a regime change that left Ketchum with an editor who “probably wanted to bury my books.” His second novel was LADIES’ NIGHT, which Ballantine rejected, precipitating a prolonged crisis of confidence. Out of that difficult period emerged Ketchum’s true second novel, HIDE AND SEEK, which didn’t appear until 1984.

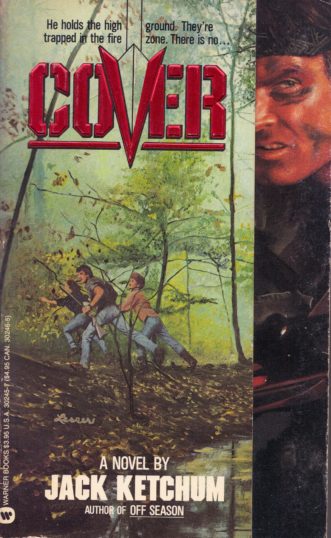

A slim account of some young punks who wind up in a haunted house, HIDE AND SEEK, allegedly inspired by the fiction of James M. Cain, is a minor effort, especially after the revelatory gut-punch of its predecessor. It was followed in 1987 by the more effective COVER, which harkens back to the precisely described carnage of OFF SEASON in its pitiless account of maladjusted city slickers stalked through the wilderness by a deranged ‘Nam vet. COVER never quite succeeds in transcending its clichéd premise, but it is nonetheless a page-burner par excellence.

A slim account of some young punks who wind up in a haunted house, HIDE AND SEEK, allegedly inspired by the fiction of James M. Cain, is a minor effort, especially after the revelatory gut-punch of its predecessor. It was followed in 1987 by the more effective COVER, which harkens back to the precisely described carnage of OFF SEASON in its pitiless account of maladjusted city slickers stalked through the wilderness by a deranged ‘Nam vet. COVER never quite succeeds in transcending its clichéd premise, but it is nonetheless a page-burner par excellence.

Ketchum’s next novel, unfortunately, was 1989’s SHE WAKES, his first overtly supernatural book–and a book that, in Ketchum’s own words, was “not very serious.” About a zombie contagion in Greece, unleased by the supernaturally endowed title character, it showcases Ketchum’s love for Grecian scenery, and contains some well described grue, but very little else. A heavily revised version of SHE WAKES was republished in 2003, but it did little to elevate what is a hopelessly dumb book in any form.

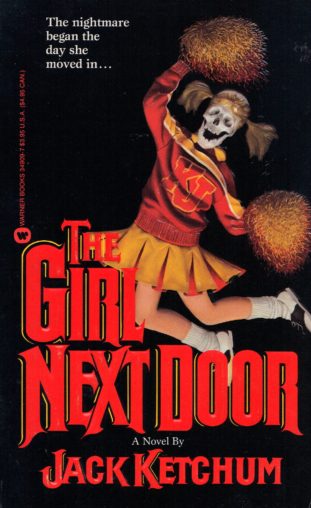

It was followed later in ‘89 by THE GIRL NEXT DOOR, Ketchum’s second masterpiece. This  novel commenced a trend many of Ketchum’s subsequent narratives would follow in that it was based on an actual crime, combined with details from the author’s own life. It’s as far removed from the splatterific excesses of OFF SEASON as it’s possible to get, yet the unsparing sensibility and honed prose are instantly recognizable. Ingeniously plotted, it begins as a nostalgic reminiscence (the first hundred or so pages contain very little that’s overtly horrific) only to morph into an almost unbearably intense horror fest without ever feeling the slightest bit unbalanced.

novel commenced a trend many of Ketchum’s subsequent narratives would follow in that it was based on an actual crime, combined with details from the author’s own life. It’s as far removed from the splatterific excesses of OFF SEASON as it’s possible to get, yet the unsparing sensibility and honed prose are instantly recognizable. Ingeniously plotted, it begins as a nostalgic reminiscence (the first hundred or so pages contain very little that’s overtly horrific) only to morph into an almost unbearably intense horror fest without ever feeling the slightest bit unbalanced.

THE GIRL NEXT DOOR’S initial publication, from Warner Books, was saddled with hopelessly trashy skeleton cheerleader cover art (allegedly inspired by the poster for the 1987 flick RETURN TO HORROR HIGH). If one wanted to really piss off Ketchum in an interview, all one need do was mention THE GIRL NEXT DOOR’s “stupid fucking cover” (as Ketchum termed it on more than one occasion). I myself held off reading the novel for years due to that cover, which portended a shitty Zebra Books potboiler rather than the reality-based blood-curdler the novel was and still is. Clearly many others held off reading it as well, as the novel, despite its undeniable qualities (it’s now routinely cited as one of the top ten horror novels of all time) received shockingly little attention.

What followed was OFFSPRING, the 1991 sequel to OFF SEASON (and the novel that introduced me to Ketchum back in ‘92). Its primary reason for being, Ketchum once suggested, was to get the earlier book back into print, but that didn’t happen, and no wonder: OFFSPRING’s distribution, by Diamond Books, was handled even more poorly than Warner Books’ notoriously fumbled rollout of THE GIRL NEXT DOOR.

What followed was OFFSPRING, the 1991 sequel to OFF SEASON (and the novel that introduced me to Ketchum back in ‘92). Its primary reason for being, Ketchum once suggested, was to get the earlier book back into print, but that didn’t happen, and no wonder: OFFSPRING’s distribution, by Diamond Books, was handled even more poorly than Warner Books’ notoriously fumbled rollout of THE GIRL NEXT DOOR.

OFFSPRING is everything you’d expect in a sequel, matching OFF SEASON’S gore quotient (no mean feat!) and adding quite a few unexpected elements, such as a character who’s a vicious psychopath—and so makes an excellent foil for the cannibal family, who once again face down a band of clueless city slickers. Here Ketchum proves yet again that his flair for suspense and sheer brutality remains unmatched, resulting in a great, gut-churning, mind-roasting read. My only beef is with the cloying happy ending, which feels completely out of place in such an otherwise uncompromising story.

Regarding 1995’s JOYRIDE (or, as it’s known in the UK, ROAD KILL), it is the very definition  of relentless. It’s about a woman who together with her lover murders her abusive hubbie. The crime seems to go off without a hitch, but there’s a witness who just happens to be a total lunatic. This maniac promptly tracks the murderers down, and enlists them in a killing spree that reaches unimaginable heights. So assured is Ketchum’s prose that even the frequent flashbacks, usually an annoyance, never compromise the book’s narrative momentum.

of relentless. It’s about a woman who together with her lover murders her abusive hubbie. The crime seems to go off without a hitch, but there’s a witness who just happens to be a total lunatic. This maniac promptly tracks the murderers down, and enlists them in a killing spree that reaches unimaginable heights. So assured is Ketchum’s prose that even the frequent flashbacks, usually an annoyance, never compromise the book’s narrative momentum.

Ketchum followed up this triumph with the lesser STRANGLEHOLD, a.k.a. ONLY CHILD, that same year. It’s a return to the sober horror of THE GIRL NEXT DOOR in its based-on-fact account of a woman who has the misfortune to marry an outwardly charming sociopath. The novel is an impacting work overall, but it lacks focus; indeed, it feels quite disjointed in its narrative construction, beginning as a horrific case study and morphing, not at all smoothly, into a courtroom drama that concludes in the bleakest manner imaginable.

The year 1995 also gave us RED, which marked something of a change of pace. The “nicest” of Ketchum’s novels, I’m convinced that had it been packaged as a mainstream thriller it would have garnered its author universal critical acceptance and a much vaster audience. The title character is a dog, who in the opening pages gets its head blown off by a teenaged punk. Red’s superbly characterized owner is the sixtyish Avery Ludlow, who attempts to enact justice for his dog’s death, leading to a brutal cycle of harassment, assault and murder.

It should be noted that RED initially appeared as a UK-only publication. It seemed that in the mid-nineties Ketchum was destined to follow the lead of his colleague Richard Laymon, who for much of the decade was unable to find publishers for his books in his native country. That all changed, however, in 1997, when Overlook Connection Press released a limited edition hardcover printing of THE GIRL NEXT DOOR.

That hardcover, which came complete with enthusiastic write-ups by Stephen King, Christopher Golden, Lucy Taylor, Edward Lee and Philip Nutman, succeeded in finally igniting public interest in this shamefully underrated author. Suddenly Jack Ketchum was a hot property, and THE GIRL NEXT DOOR a “contemporary classic” that everyone in the horror-verse claimed to have read back when it was first published. Right!

1998 saw the publication of Ketchum’s first short fiction collection, THE EXIT AT TOLEDO BLADE BOULEVARD, and the debut of his long-suppressed second novel LADIES’ NIGHT. As the saying goes, even Picasso had his off days…and so, clearly, did Jack Ketchum. LADIES’ NIGHT is a quasi-science fictionish account of a toxic spill that turns all women vicinity into zombie bitches from Hell. As was adequately proven in SHE WAKES, zombie fiction is not Ketchum’s forte, and results in a silly and implausible book.

1998 saw the publication of Ketchum’s first short fiction collection, THE EXIT AT TOLEDO BLADE BOULEVARD, and the debut of his long-suppressed second novel LADIES’ NIGHT. As the saying goes, even Picasso had his off days…and so, clearly, did Jack Ketchum. LADIES’ NIGHT is a quasi-science fictionish account of a toxic spill that turns all women vicinity into zombie bitches from Hell. As was adequately proven in SHE WAKES, zombie fiction is not Ketchum’s forte, and results in a silly and implausible book.

1999 was a busy year on the Ketchum front. ‘99 saw the long-awaited reprinting of OFF SEASON in the form of an “Unexpurgated Edition” from Overlook Connection Press, which further bolstered the fame of this “new” author, and a nicely designed chapbook from James Cahill Publishing entitled THE DUST OF HEAVENS. The latter is a moving and horrific memoir about the descent into schizophrenia of a longtime friend of Ketchum’s that was later republished in the nonfiction anthology BOOK OF SOULS. Also appearing in 1999 was RIGHT TO LIFE, a Cemetery Dance Press published novella.

RIGHT TO LIFE once again relates a based-on-fact story, this one concerning a woman, three months pregnant by an extramarital lover, who’s kidnapped on her way to an abortion clinic. What this gal’s lunatic captors put her through involves rape, mutilation and all manner of psychological torture that normal folks would be better off not even thinking about. As usual with a Ketchum book, it’s a mighty uncomfortable, but not unsatisfying, read.

Moving forward two years, we arrive at the publication of Ketchum’s longest novel, and one of his all-around best works: THE LOST. As was the  case with so many Ketchum books, it was released as a paperback original, complete with trashy horror-novel cover art—yet THE LOST, like all Ketchum’s greatest work, far transcends the horror label (or, for that matter, pretty much any label). It is yet again inspired by true life events, in this case the killings of Charles Schmid, the so-called Pied Piper of Tucson. As was his custom, Ketchum transplanted the particulars of this case to his own upstate New York background, with the time-frame here being the late 1960s.

case with so many Ketchum books, it was released as a paperback original, complete with trashy horror-novel cover art—yet THE LOST, like all Ketchum’s greatest work, far transcends the horror label (or, for that matter, pretty much any label). It is yet again inspired by true life events, in this case the killings of Charles Schmid, the so-called Pied Piper of Tucson. As was his custom, Ketchum transplanted the particulars of this case to his own upstate New York background, with the time-frame here being the late 1960s.

The Schmid stand-in is Ray, a teenage sociopath who callously kills two girls. His best buddy and girlfriend both witness the act, but do nothing. Flash forward four years, to the time of the Manson murders: Ray is still a hopeless sociopath and his friends are still sniveling wimps, but a few new characters have entered the fray. These include a cop determined to make Ray pay for the murders he committed and a high-society gal who has the misfortune to cozy up to an increasingly deteriorating Ray. Despite THE LOST’S near-400 page length, not a word is wasted as the story moves inexorably toward its nerve-shattering climax. I won’t give anything away, except to say that Ray will shed more blood by time the story is done–much more!

2001 also saw the publication of a novella entitled THE PASSENGER in the Richard Chizmar edited NIGHT VISIONS 10 (later republished in the Leisure Press paperback edition of RED). It doesn’t exactly break new ground in the Ketchum-verse, but it does prove that he never lost his ability to craft a lean, very mean story. It features a woman attorney unwisely accepting a ride with a lady claiming to be a high school chum, leading to an unbelievably sordid odyssey in which we’re once again made privy to the fact that the disturbing charge of Ketchum’s fiction isn’t necessarily due to the violence, but rather its sheer relentlessness.

For better or worse, from that point on novellas were all we’d get from Ketchum in terms of long-form fiction. Those novellas included 2003’s THE CROSSINGS, a Ketchum-ized western involving a tough journalist, a veteran gunfighter and a Mexican woman who’s been raped and hideously wounded by a band of scumbags. Aside from some vaguely supernatural business involving ancient Aztec deities this is pretty standard western revenge stuff, but Ketchum’s inimitable prose gives this tale a hard-bitten flavor all its own. The fearsome WEED SPECIES from 2006 starts out in wrenching fashion, with the teenaged Sherry drugging her little sister so her depraved boyfriend Owen can rape her. Guess what? Things only get steadily worse from there, as Sherry and Owen mature into full-fledged sociopaths, jointly raping unsuspecting young women and often murdering them. A winsome account, from an author who was at his spare, unflinching best. Finally there was 2008’s OLD FLAMES, which explores the hopeless existence of Dora, who’s had terrible luck with men. She decides to track down her first-ever love Jim and insinuate herself into his life. All the expected disturbing brutality is in store, but this novella is distinguished by an entirely convincing story and spot-on character development.

One especially happy development was the inclusion of Ketchum in Leisure’s fabled mass market horror line. Starting with the Leisure publications of RED in 2002 and the short story anthology PEACEABLE KINGDOM in ‘03 (which featured classic Ketchum tales like “The Box” and “The Rifle”), Ketchum, alongside younger horror scribes like Brian Keene, Jeff Strand and Bryan Smith, became one of Leisure’s star authors, even though Ketchum’s Leisure publications were nearly all reprintings of his earlier books.

One especially happy development was the inclusion of Ketchum in Leisure’s fabled mass market horror line. Starting with the Leisure publications of RED in 2002 and the short story anthology PEACEABLE KINGDOM in ‘03 (which featured classic Ketchum tales like “The Box” and “The Rifle”), Ketchum, alongside younger horror scribes like Brian Keene, Jeff Strand and Bryan Smith, became one of Leisure’s star authors, even though Ketchum’s Leisure publications were nearly all reprintings of his earlier books.

Then there were the film adaptations. They commenced with 2006’s THE LOST, a long-in-the-works film by writer-director Chris Sivertson that showed Ketchum had attained enough cachet on the horror circuit that he was given an above-the-title credit. The film is a faithful and affecting adaptation of the novel of the same name, perfectly capturing Ketchum’s minimalistic storytelling and character-based aesthetic. THE GIRL NEXT DOOR, from 2007, is likewise an extremely faithful adaptation, and impressively replicates Ketchum’s focus and dark trajectory. It’s just too bad about the climax, which collapses the novel’s nail-biting final third into an overly abrupt wrap-up. 2008’s RED is another strong adaptation that despite a troubled production, which saw the film’s initial director Lucky McKee replaced midway through filming, emerges as a compelling piece of work with an expert performance by Brian Cox. OFFSPRING, which appeared in 2009, was scripted by Ketchum himself, and nicely captures his pared-down storytelling, although the film’s evident low budget and severely uneven performances hamper its impact. Finally there was 2011’s stylish and atmospheric THE WOMAN, a Lucky McKee directed sequel to OFFSPRING, with one of that film’s stars Pollyanna McIntosh acquitting herself quite well in the title role of a forest-dwelling cannibal, captured by a seemingly mild-mannered lawyer who subjects her to all manner of horrific torture.

THE WOMAN initially appeared as a 2010 novella, co-authored by Ketchum and McKee. The first of two books by this pair, it’s a decent enough  chunk of nastiness, albeit not up to the high standards of Ketchum’s previous books, marred by one-dimensional characterizations and many less-than-believable plot developments. The book’s most memorable portion is a more-or-less standalone fifty page vignette called “Cow” (which didn’t make it into in the film version), related in the form of diary entries by a man who’s forced to become a human stud farm to the title character and her cannibal brood.

chunk of nastiness, albeit not up to the high standards of Ketchum’s previous books, marred by one-dimensional characterizations and many less-than-believable plot developments. The book’s most memorable portion is a more-or-less standalone fifty page vignette called “Cow” (which didn’t make it into in the film version), related in the form of diary entries by a man who’s forced to become a human stud farm to the title character and her cannibal brood.

It was followed in 2012 by I’M NOT SAM, Ketchum’s second collaboration with McKee, and, sadly, his final novel (or, rather, novella) length work of fiction. I wish I could say it marked a triumphant capstone to Ketchum’s career, but that, I’m afraid, would be inaccurate. A short story stretched to novella length (with all the noticeable flaws that entails), I’M NOT SAM is a two-parter about Samantha, a woman surgeon who inexplicably awakens one day claiming to be a child named Lily. The book’s first portion is told from the viewpoint of Samantha’s husband Patrick, who still lusts after his wife despite her childlike persona, and the second from that of Samantha, who has her own take on what’s been happening. The book concludes, at least, with an impacting shock that closes this twisted story out on a reasonably satisfying note.

To his credit, Ketchum stayed busy for the remainder of his life, putting out a volume of poetry (2013’s NOTES FROM THE CAT HOUSE) and three nonfiction collections (2008’s BOOK OF SOULS, 2013’s TURING JAPANESE and 2014’s WHAT THEY WROTE). He also took part in the 2013 meta-novel SIXTY-FIVE STIRRUP IRON ROAD in collaboration with Brian Keene, Edward Lee, J.F. Gonzalez, Bryan Smith, Wrath James White, Nate Southard, Ryan Harding and Shane McKenzie. The novel was conceived as a benefit for the ailing horror author Tom Piccirilli, so it deserves plaudits for attempting to do some good. But the fact is that none of the eight authors mentioned above can hold a candle to Jack Ketchum.

In fact, I contend that it’s an insult to include Ketchum in the “Hardcore Horror” line-up, as he increasingly was toward the end of his life. While Ketchum did indeed write horror stories that can be termed hardcore in their approach, the skill and nuance of his writing places it far beyond the numbing gross-out spectacles (such as SIXTY-FIVE STIRRUP IRON ROAD) that have become so prevalent in the field. Ketchum was truly in a league of his own, a league that has tragically now passed into history.

In fact, I contend that it’s an insult to include Ketchum in the “Hardcore Horror” line-up, as he increasingly was toward the end of his life. While Ketchum did indeed write horror stories that can be termed hardcore in their approach, the skill and nuance of his writing places it far beyond the numbing gross-out spectacles (such as SIXTY-FIVE STIRRUP IRON ROAD) that have become so prevalent in the field. Ketchum was truly in a league of his own, a league that has tragically now passed into history.

R.I.P. Dallas Mayr/Jack Ketchum.