Q: What is an Illustrated Oddment?

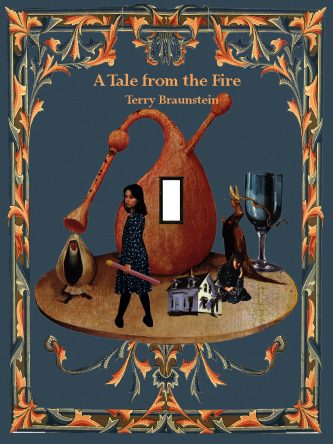

A: It’s a book that in its gorgeous strangeness and fascination deserves some ink on this site, even if I (for whatever reason) can’t really justify writing a full review. Case in point: A TALE FROM THE FIRE, a wholly unique quasi-narrative picture book created by the famed collage artist TERRY BRAUNSTEIN in 1995.

Running just 16 pages and containing a mere seven sentences of text, A TALE FROM THE FIRE is not what you’d call expansive. It is bold and eye-catching, however, picturing a young girl (model Sydney Bays) interacting with famous paintings that include Hieronymus Bosch’s “The Garden of Earthly Delights,” Rene Magritte’s “Personal Values,” Peter Bruegel’s “Return of the Herd” and Edward Hopper’s “Hodgkin’s House.” The girl is depicted traversing the surreal and oft-horrific landscapes of these canvases in an odyssey whose mythological overtones are elucidated on the inside dust jacket, which recounts the myth of the phoenix. I really wish there were more to it, but the gorgeous design of the book is undeniable, with the Macintosh PC that was used to create its imagery deserving of partial authorial credit.

Running just 16 pages and containing a mere seven sentences of text, A TALE FROM THE FIRE is not what you’d call expansive. It is bold and eye-catching, however, picturing a young girl (model Sydney Bays) interacting with famous paintings that include Hieronymus Bosch’s “The Garden of Earthly Delights,” Rene Magritte’s “Personal Values,” Peter Bruegel’s “Return of the Herd” and Edward Hopper’s “Hodgkin’s House.” The girl is depicted traversing the surreal and oft-horrific landscapes of these canvases in an odyssey whose mythological overtones are elucidated on the inside dust jacket, which recounts the myth of the phoenix. I really wish there were more to it, but the gorgeous design of the book is undeniable, with the Macintosh PC that was used to create its imagery deserving of partial authorial credit.

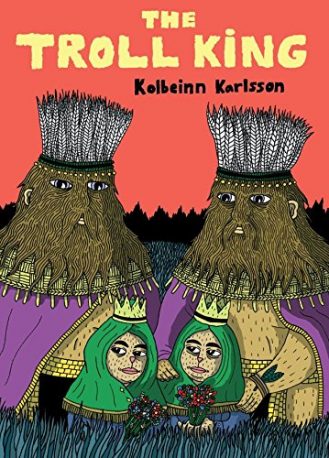

2010’s THE TROLL KING is a graphic novel scripted and drawn by the  Swedish cartoonist KOLBEINN KARLSSON, who deals with European myth and folklore in his own thoroughly idiosyncratic manner. It’s about two forest-dwelling gay trolls who are granted offspring by the Gods, only to have those children run away after discovering that the rustic life isn’t as idyllic as it might seem.

Swedish cartoonist KOLBEINN KARLSSON, who deals with European myth and folklore in his own thoroughly idiosyncratic manner. It’s about two forest-dwelling gay trolls who are granted offspring by the Gods, only to have those children run away after discovering that the rustic life isn’t as idyllic as it might seem.

This account is intercut with other like-minded tales, one involving a dwarf who dreams of falling into a river and entering a psychedelic realm of gods and monsters, and another about a mutating carrot, and still another about a pair of green goblins who make a most fortuitous discovery. Precisely how all these accounts connect–or if they do at all–I’m not sure.

There’s very little dialogue, with the strange and frequently gruesome imagery being all-important. The artwork has a staunchly handmade, primitivistic sheen, albeit with a sophisticated design sense that compels one to keep reading even when the storytelling is at its most confounding.

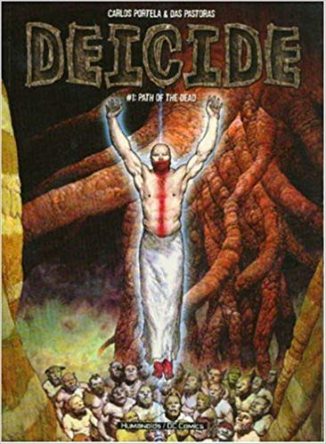

While on the subject of Euro-comics, let’s take a look at the 2004 Spanish import DEICIDE: PATH OF THE DEAD by CARLOS PORTELA and DAS PASTORAS, which reads like a lunatic variant on CONAN THE BARBARIAN.

While on the subject of Euro-comics, let’s take a look at the 2004 Spanish import DEICIDE: PATH OF THE DEAD by CARLOS PORTELA and DAS PASTORAS, which reads like a lunatic variant on CONAN THE BARBARIAN.

DEICIDE was evidently inspired by the nutzoid comic book scripting of Alejandro Jodorowsky, and contains a wealth of bizarre and excessive elements. The narrative (such as it is) involves a muscleman living in a tribal world filled with all manner of inhuman creatures who embarks on a journey to save the soul of his beloved. He teams up with a cloven-hoofed, lion-headed man, and the two have all sorts of adventures that, frankly, grow repetitive and dull very quickly. Thankfully the artwork by Das Pastoras is eye-popping, particularly in its depiction of slimy critters; a rendering of a guy’s body dissolving into hordes of toothy reptiles is especially memorable.

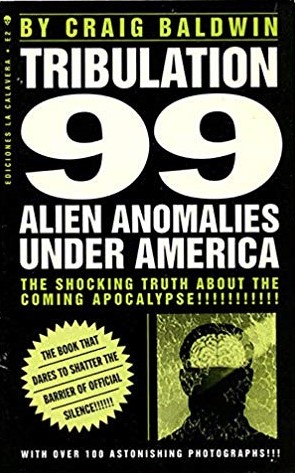

Worth a look is TRIBULATION 99: ALIEN ANOMALIES UNDER AMERICA, a 1991 companion book to the similarly titled underground film (a longtime favorite of mine) by writer-director CRAIG BALDWIN. Baldwin is also credited  with authoring this book, which transcribes the narration from the film together with several representative stills.

with authoring this book, which transcribes the narration from the film together with several representative stills.

The flick is a positively mind-roasting found footage collage that mixes the real-life facts of America’s military interventions in South America with a wild account of space aliens wreaking havoc from under the earth. Every conceivable conspiracy theory is addressed along the way, and in a manner that forces us to ponder the media’s representations of truth and fiction. Of course much of the effect was contingent upon the film’s ultra-kinetic imagery, which is lost in the printed format. The book is useful, at least, in deciphering the jam-packed narrative, which wasn’t presented in entirely coherent fashion onscreen.

THE TATTOOED MAP by BARBARA HODGSON is a 1995 novel presented as a copiously illustrated Nick Bantock-esque hardcover. Not that author Barbara Hodgson ever integrates the artwork into the text in any meaningful way, as what  we get in the way of visual aid are mostly drawings and handwriting in the page margins detailing inconsequential aspects of the travels of the two main characters (restaurant tabs, hotel expenses, etc). But the story this book tells is an intriguing one.

we get in the way of visual aid are mostly drawings and handwriting in the page margins detailing inconsequential aspects of the travels of the two main characters (restaurant tabs, hotel expenses, etc). But the story this book tells is an intriguing one.

The tale is related in the form of diary entries by Lydia, who’s vacationing in Morocco with her partner Christopher. After several days of aimless travel Lydia wakes up one morning with what look like flea bites on one of her hands. The marks grow increasingly pronounced, and eventually form a tattoo that appears to depict a map of some unknown country. But then around the halfway point (one peculiarity of the book is that it doesn’t have any page numbers) Lydia abruptly disappears, and Christopher takes over the narrative with his own diary entries–and things only get progressively stranger.

What are we to make of this bizarre and ultimately unresolved story? Much of it has a vaguely SHELTERING SKY vibe, spiced with the exotic supernaturalism of THE ARABIAN NIGHTMARE. About the best I can say for it is that, once again, it’s intriguing—and indeed, maybe that’s all that need be said

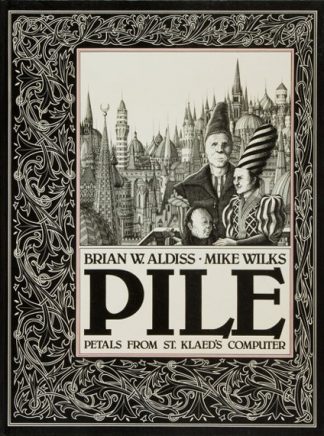

1979’s large format hardback PILE began as (according to the back cover description) a series of black and white drawings by British artist MIKE WILKS, with a verse poem created by sci fi legend BRIAN W. ALDISS to tie those pictures together. The unique circumstances of PILE’S creation would appear to explain why its images don’t always match Aldiss’ story. Highly metaphoric in nature, that story concerns an otherworldly seaside city called Pile, marked by insanely ornate architecture and a perpetually warring populace.

Following the latest of many battles one Prince Scart addresses Pile’s all-powerful computer of St. Klaed, imploring it to smite his enemies at any cost. The computer complies, resulting in Pile literally crumbling into the sea. From there Scart is abducted by the monstrous inhabitants of a strange ship that dives beneath the waves and deposits him in the kingdom of Elip. This place is a mirror image of Pile ruled by its own computer, which is far more mystically inclined than St. Klaed, and which helps effect a profound spiritual rebirth.

Aldiss’ verse is impressive and (appropriately) confounding, but PILE’S true selling point is the extraordinary artwork of Mike Wilks. Overpowering in its scope, grandeur and impeccably proportioned architecture, Wilks’ art can be appreciated independent of the text—which, it seems, was the initial intent.

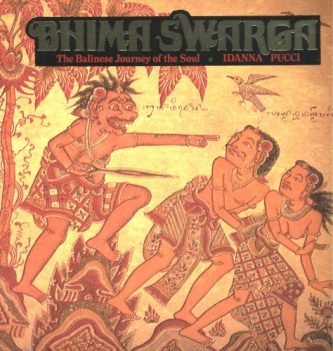

Somewhat similar in conception is 1992’s BHIMA SWARGA by IDANNA PUCCI, which fleshes out the story related by a series of sequential paintings found on the ceiling of the Kertha Gosa pavilion in Bali. The narrative in question hails from the Balinese version of the MAHABHARATA, and tells the story of a Dante-esque trip through the underworld taken by Bhima Swarga, a heroic warrior determined to rescue his parents from Hell. Bhima’s actions set off a war among Hell’s demons, who are eventually joined in their fight by Yama, the lord of Hell. Unsurprisingly, the impossibly heroic Bhima wins the fight, and from there ascends to the over world, where he incites another apocalyptic battle, and proves that “Even in Heaven, Bhima’s power was unmatched.”

Somewhat similar in conception is 1992’s BHIMA SWARGA by IDANNA PUCCI, which fleshes out the story related by a series of sequential paintings found on the ceiling of the Kertha Gosa pavilion in Bali. The narrative in question hails from the Balinese version of the MAHABHARATA, and tells the story of a Dante-esque trip through the underworld taken by Bhima Swarga, a heroic warrior determined to rescue his parents from Hell. Bhima’s actions set off a war among Hell’s demons, who are eventually joined in their fight by Yama, the lord of Hell. Unsurprisingly, the impossibly heroic Bhima wins the fight, and from there ascends to the over world, where he incites another apocalyptic battle, and proves that “Even in Heaven, Bhima’s power was unmatched.”

The bulk of the story naturally focuses on the tortures undergone by the sinners of Hell: people are sawed in half, boiled, set on fire, submerged in lava and ripped apart by animals. There’s even a depiction of an inflamed hemorrhoid getting pulled and squeezed by a demon.

The layout of the book is simple enough, with photographic reproductions of the paintings of the Kertha Gosa ceiling with text by author Idanna Pucci explaining what’s happening in them, preceded by a lengthy introduction outlining the history of the pavilion–it was apparently constructed in the early 1700s and its ceiling repainted at least twice—and Balinese culture in general. The paintings, for the record, are marked by strangely proportioned figures and an oddly flat, two-dimensional aesthetic, which are apparently mainstays of classical Balinese art. Beyond that my only real complaint is that the author isn’t much of a storyteller, with the flat prose and wooden dialogue being frequent and annoying distractions.