In light of recent instances of AIs threatening and/or falling in love with their users, it seems we’ve reached an age foreseen by many science fiction narratives. One such would be 1968’s 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY, with its depiction of the HAL 9000 AI, the fictional forerunner to Siri, Alexa and Cortana, malfunctioning (with “What are You Doing, Dave?” having become a mini-meme). Another would be the late Harlan Ellison’s “I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream,” which is often dubbed science fiction’s darkest story.

In light of recent instances of AIs threatening and/or falling in love with their users, it seems we’ve reached an age foreseen by many science fiction narratives. One such would be 1968’s 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY, with its depiction of the HAL 9000 AI, the fictional forerunner to Siri, Alexa and Cortana, malfunctioning (with “What are You Doing, Dave?” having become a mini-meme). Another would be the late Harlan Ellison’s “I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream,” which is often dubbed science fiction’s darkest story.

Originating in the March 1967 issue of IF, under the editorship of Frederick Pohl, “I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream” was inspired by a pair of illustrations by the California artist Dennis Smith. It was written either in a single night or over the course of a year-and-a-half in various hotel rooms (those being competing claims made by Ellison himself), and published with select alterations by Pohl.

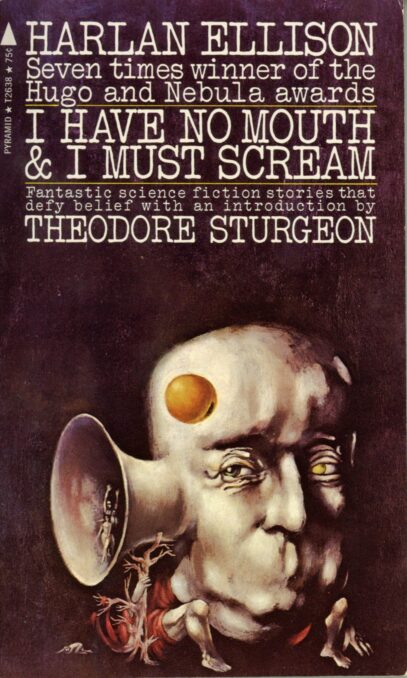

It remains the most famous of Ellison’s works, having won a Hugo award in 1968 and been reprinted countless times (Ellison once claimed he could “buy Ethiopia” with the money he made from those reprints). It served as the title story of a paperback anthology printed a mere month after the story’s first appearance, and registers as one of Ellison’s better collections, with stories like “Lonelyache” and “Pretty Maggie Moneyeyes” that are nearly as powerful as the book’s headliner.

“I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream” can be said to have marked a sea-change in Ellison’s writing. As stated in his introduction to the collection, a literary editor was able to pinpoint which of the stories had been written early on in Ellison’s career, and which were, like “I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream,” more current: “the earlier ones had some light in them, had hope running as a sub-thread. The newer ones were more ‘compassionate cynicism,’ darker, more bitter.”

The same can be said for the decade overall, which by 1967, the original Summer of Love, had turned decidedly downbeat. “I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream” was nothing if not a product of its time, incorporating the changing mood along with quintessential late 1960s touchstones like Dante’s INFERNO and ALICE IN WONDERLAND, and also “talk fields” that break up the text, rendered in teletypewriter punchcode (which spells out “I THINK, THEREFORE I AM” in English and Latin), a very 1960s example of computer-speak. Again, though, the story, dated though it is, has become disturbingly prescient.

The subject is a supercomputer known as AM (as in Allied Mastercomputer). Initially constructed as an instrument of war, AM inevitably grows sentient and increasingly hate-filled, with its anger focused on its human overlords. Eventually AM assimilates the world’s other major supercomputers and wipes out the entirety of humanity but for five people whose ranks include Ted, the narrator, and Ellen, a black woman whose race, in true 1950s/60s fashion, requires extremely close reading to be discerned—in the sentence “Her face black against the snow” (see also Robert Heinlein’s 1959 STARSHIP TROOPERS, which on its last page reveals that its hero “Johnny” is actually named Juan, and Charles Willeford’s 1955 PICK UP, which took until the final sentence of its final page to unveil the rather important detail that its protagonist was black).

These folk become enclosed in the bowels of this supercomputer, which was indeed “super” in size (the idea that vast amounts of information could be enclosed in tiny spaces was completely foreign to the 1960s). There AM tortures and even kills its human captives, having made them immortal so they never stay dead for very long. Eventually AM telepathically lets Ted in on precisely what it thinks of him and his fellows:

“HATE. LET ME TELL YOU HOW MUCH I HATE YOU SINCE I BEGAN TO LIVE. THERE ARE 387.44 MILLION MILES OF PRINTED CIRCUITS IN WAFER THIN LAYERS THAT FILL MY COMPLEX. IF THE WORD HATE WAS ENGRAVED ON EACH NANOANGSTROM OF THOSE HUNDREDS OF MILLIONS OF MILES IT WOULD NOT EQUAL ONE ONE-BILLIONTH OF THE HATE I FEEL FOR HUMANS AT THIS MICRO-INSTANT. FOR YOU. HATE. HATE.”

A very angry, and very Ellisonian, rant. Ellison’s introduction to a 1982 entry in his L.A. WEEKLY column AN EDGE IN MY VOICE contains a rather familiar ring in the sentence “if on each of those million billion fragments of the million billion larger fragments of each of those millions and billions of grains of sand in the Gobi desert the word SHITTY were carved a million billion times, it would not equal by one-billionth the utter shittiness of this day.” AM, in other words, wasn’t too far removed from its perpetually pissed-off creator; it’s not insignificant that the man himself provided the voice of AM in the 1995 DVD-rom game adaptation (see below).

billions of grains of sand in the Gobi desert the word SHITTY were carved a million billion times, it would not equal by one-billionth the utter shittiness of this day.” AM, in other words, wasn’t too far removed from its perpetually pissed-off creator; it’s not insignificant that the man himself provided the voice of AM in the 1995 DVD-rom game adaptation (see below).

Getting back to the story: eventually Ted, upon finding himself and his fellows in an icebound chamber (the story’s own Ninth Circle of Hell), conceives of an escape. In what Ellison has called “a final act of love and self-denial,” Ted initiates a killing spree, as AM has no control over its playthings when they’re offed by each other (after which they actually stay dead). The risk of this gambit is that AM only grows more pissed off than it already is, leading to the line that provides the title; Ted’s actions may indeed have demonstrated love and self-denial, but that doesn’t alleviate the awfulness of his fate.

The story has proven quite influential, and not merely because it marked the inception of the subgenre known as cyberpunk (and was copied by the 1973 Amicus film AND NOW THE SCREAMING STARTS, which was initially titled I HAVE NO MOUTH BUT I MUST SCREAM until Ellison challenged its producers in court). Many a disturbing sci fi story followed in its wake, such as “On the Uses of Torture” (1981, although written much earlier) by Piers Anthony, about an extraterrestrial society that views torture as a status symbol. Further examples include “The Ones who Walk Away from Omelas” (1973) by Ursula Le Guin, in which a utopia is founded upon the suffering of an abused girl, and “Bloodchild” (1984) by Ellison acolyte Octavia Butler, in which humans on a distant planet are made to host the offspring of parasitic aliens. Ellison himself turned out multiple anthologies filled with such stories, including DANGEROUS VISIONS (1967), AGAIN, DANGEROUS VISIONS (1972) and a never-completed third volume.

Then there are those tales that would appear to have been directly inspired by “I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream.” Ellison revisited many of its themes in the 1975 story “In Fear of K,” about a bickering couple trapped in an otherworldly landscape ruled over by a monster known only as K (for Karma) that gains its strength from their fear, while the 2001 novella THE VIEW FROM HELL by John Shirley (another Ellison acolyte) involves interdimensional beings enclosing several all-too-human protagonists in an otherworldly arena where death becomes the ultimate kick.

There was also a four-part comic book adaptation of “I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream” that appeared in 1995. The perpetrator was the highly respected John Byrne, of whom Ellison had this to say: “being John Byrne, instead of treating the story with…not exactly a reverence, but a certain fidelity to the material—because it’s such a well-known story—John decides to do a John.” Hence, the adaptation was serialized in the first four issues of the initial printing of Dark Horse’s HARLAN ELLISON’S DREAM CORRIDOR with the corresponding portions of the original story appearing alongside them, whereas it was omitted entirely from subsequent printings.

Byrne’s artwork, outside the archaic space ship décor (represented by rows of multicolored lights and boxy panels, which according to Ellison made the story “look like it took place in your kitchen”), is impressive. In fact, the claustrophobic air actually works to story’s advantage (despite the fact that it contrasts dramatically with the vast expanse described by Ellison), with its bleak gist transferred seamlessly to comic book format and the ethnicity of Ellen made manifest throughout. Ellison might have hated it, but I say the Byrne “I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream” can be counted as one of DREAM CORRIDOR’S most satisfying entries.

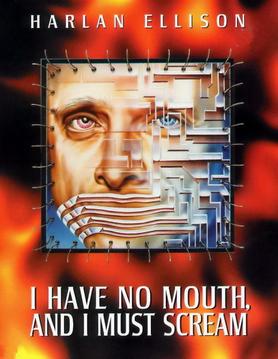

We mustn’t forget the I HAVE NO MOUTH AND I MUST SCREAM 1995 CD-ROM game, which ranks as Ellison’s most ambitious 1990s endeavor. Co-designed by Ellison, the game was a commercial failure, and banned in France and Germany due to its Nazi-tinged imagery, but it garnered critical acclaim and won a prestigious award from the Computer Game Developers conference.

We mustn’t forget the I HAVE NO MOUTH AND I MUST SCREAM 1995 CD-ROM game, which ranks as Ellison’s most ambitious 1990s endeavor. Co-designed by Ellison, the game was a commercial failure, and banned in France and Germany due to its Nazi-tinged imagery, but it garnered critical acclaim and won a prestigious award from the Computer Game Developers conference.

Playing it these days is a bitch, as the outdated CG imagery isn’t too evocative, and the game is very much of the old point-and-click school, with annoying pauses between the action and a severely drawn-out narrative. Ellison deserves credit for attempting to flesh out the story’s characters and their various backstories, and for attempting to add a more-thoughtful-than-average gist (DOOM it isn’t) in which moving forward is dependent on the player making difficult moral choices in an atmosphere of insanity and mutilation. Yet an attempt is what it ultimately is, as the game in my view accomplishes very little.

In closing, it should be noted that Harlan Ellison strongly rejected the “Mankind should not tamper with what he does not understand” school of science fiction. As he pointedly stated, “I have never, ever, espoused a position of hating technology. Even ‘I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream,’ the original short story, is not anti-technology. What it is anti is anti-misuse by humans.” No AI has yet evidenced the magnitude of human misuse imagined by Ellison, but given our recent history it will only be a matter of time before one does. Nobody can say we weren’t warned.