In the modern horror pantheon there are a handful of books so revered their publications have been touted as Major Events in the field. Examples include ROSEMARY’S BABY (1967), GHOST STORY (1979) and BOOKS OF BLOOD (1985). HOUSE OF LEAVES, written by Mark Z. Danielewski—or as he’s become known, MZD—and published in 2000, deserves a place in that pantheon.

In the modern horror pantheon there are a handful of books so revered their publications have been touted as Major Events in the field. Examples include ROSEMARY’S BABY (1967), GHOST STORY (1979) and BOOKS OF BLOOD (1985). HOUSE OF LEAVES, written by Mark Z. Danielewski—or as he’s become known, MZD—and published in 2000, deserves a place in that pantheon.

HOUSE OF LEAVES is a 709-page brick of a book about a Virginia based house—a word presented in blue throughout the book (as it is in this article)—that’s bigger on the inside than it is on the outside. To be more specific, the outside of this structure never changes its size or shape, yet its interior has a tendency to unexpectedly sprout lengthy hallways that lead into vast rooms containing endless stairways, inside which the laws of physics are suspended and forbidding sounds are heard.

…the outside of this structure never changes its size or shape, yet its interior has a tendency to unexpectedly sprout lengthy hallways that lead into vast rooms containing endless stairways…

The main narrative is presented in the form of a description of a movie that, as we’re informed on page one, doesn’t actually exist, and written by a character named Zampano, an old man who may likewise not actually exist. The editor is Johnny Truant, a young punk who discovers Zampano’s writings and is driven mad by them. Johnny’s own existence, the particulars of which are laid out in voluminous footnotes describing his misadventures with strippers, miscreants and illegal substances, is quite fraught, and more than lives up to his last name.

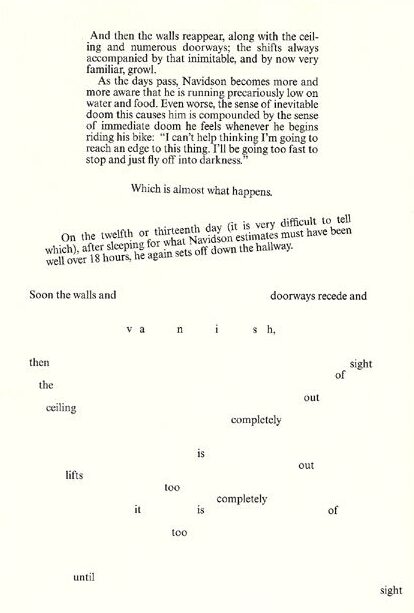

The meat of the novel lies in Zampano’s descriptions of the non-existent movie about the house. Its owner is one Tom Navidson, a Pulitzer Prize winning photographer whose sense of adventure is kindled by the endless hallways appearing in his house, and he grows obsessed with exploring them. This allows for a great deal of creative typography (text printed upside-down, backwards, etc.), and Zampano includes voluminous footnotes which co-exist (not always harmoniously) with the after-the-fact notes provided by Johnny, leading to a (deliberate) clash of voices, worldviews and fonts, and what is very likely the most torturous use of footnotes in literary history.

Yet another angle is introduced in the form of the many outrageously pretentious analyses of the film Zampano and/or Johnny insist on including, in the form of (yet more) footnotes and a couple chapters consisting of quotes (allegedly collected by Navidson’s better half Karen) about the film, purporting to be from various famous folk. The latter include Steve Wozniak, Jacques Derrida, Anne Rice, Camille Paglia, Hunter S. Thompson, Stanley Kubrick and Stephen King, whose words are all very characteristic (Thompson is quoted as saying “Your film didn’t help. It’s, well…one thing in two words: fucked…very fucked up,” while King claims “Symbols shmimbols…what we sometimes forget is that Ahab’s whale was also just a whale,” which does indeed sound very Stephen King-ish), and lend this portion of the text an overtly satiric air.

… very likely the most torturous use of footnotes in literary history.

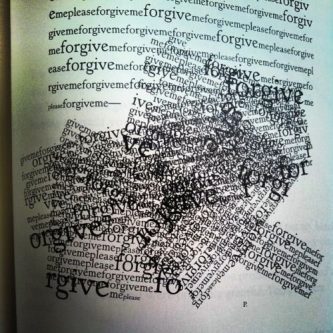

Also included are lengthy appendixes featuring photos of the exterior of the house, visual collages and a section entitled “The Three Attic Whalestoe Institute Letters,” consisting of 1980s-era missives to Johnny from his mother, who’s been institutionalized for having tried to kill his seven-year-old self. These letters begin innocently enough (“Open you heart to the kindness and stability your new family offers you. All of it will serve you well”), but in keeping with the book’s overall gist grow increasingly unhinged, with single words and phrases repeated over and over, lines of text overlapping each other, etc. Also contained in these letters are numerous passages that directly recall, or more accurately foreshadow, the details of the Navidson house (such as a reference to an “interminable corridor”).

The book as a whole can be said to replicate the properties of the house at its center, with its endless hallways that branch off and intersect each other in a monstrous, impenetrable maze. If there’s an overriding meaning to it all I’ll confess I have yet to find it (even after reading through the book twice), but can’t deny that MDZ has created an intoxicating swirl of puzzlement that’s brilliant and exasperating in equal measure. It’s also authentically chilling, boasting (in the Navidson passages) a genuinely eerie and foreboding concept, and characters whose behavior (for once in a horror story) makes perfect sense. This is to say that Navidson is understandably unnerved by the strange hallways appearing in his house, yet is just as understandably determined to see where they lead.

…authentically chilling, boasting (in the Navidson passages) a genuinely eerie and foreboding concept, and characters whose behavior (for once in a horror story) makes perfect sense.

The book was popular enough in the early 00s to make its young author a media personality. As such he was quite adapt, having clearly studied the public demeanor of “star” writers like Stephen King and Clive Barker. MZD was unerringly well spoken (as he told Rue Morgue, “The obvious juxtaposition of highbrow intellectual garble and lowbrow oral storytelling in the book is meant to bring to light that intelligence cannot be denoted by collegiate degrees”) and built up an interesting (and likely fictitious) mythology surrounding his book.

That mythology, claiming that the text initially become a sensation on the internet in the late nineties (of which I’ve been unable to find any evidence), was replicated on the book jacket, which claims “No one could have anticipated the small but devoted following this terrifying story would soon command,” a following that apparently included old folk who “not only found themselves in these strangely arranged pages but also discovered a way back into the lives of their estranged children.” Furthermore, MZD had a semi-famous sister: the singer-songwriter Poe (a.k.a. Anne Decatur Danielewski), who helped promote the book and released an album, entitled HAUNTED, that appeared around the time the book was first published, and shared many of its themes.

Certainly the novel seemed quite unprecedented, at least to those unfamiliar with nineties-era horror literature. Celebrated non-genre affiliated experimentalists like B.S. Johnson and Coleman Dowell tend to be evoked in discussions about HOUSE OF LEAVES, while the book most often coined by reviewers in search of like-minded tomes being David Foster Wallace’s magnificently unreadable INFINTE JEST (1996), which like HOUSE OF LEAVES was a hefty experimental tome that was heavy on digressions and footnotes. The major difference between the two books is that HOUSE OF LEAVES was anything but unreadable—no less an authority on popular literature than Stephen King has proclaimed it “bizarre but compulsively readable”—and is, although MZD and quite a few of his supporters have tried to distance it from the field, very much a horror novel.

Furthermore, it was a horror novel that followed, and arguably capped, a very evident trend suffusing the field. Literary horror, contrary to what has often been claimed, was not “dead” in the nineties. Rather, with end of the Cold War that informed so much of the previous decades’ scare literature and other real-life upheavals, the so-called Horror Boom of the seventies and eighties met its inevitable end, and the genre was forced into an evolve-or-die position.

In this atmosphere genre specialists were forced to abandon, or at least modify, their output. The prolific British horrorist Ramsey Campbell, for instance, opted for quirky crime-horror hybrids (with THE COUNT OF ELEVEN, THE ONE SAFE PLACE and THE LAST VOICE THEY HEAR), as did Peter Straub (with MYSTERY, THE THROAT, THE HELLFIRE CLUB and MR. X), while other horror scribes, such as Robert McCammon and William Schoell, ceased writing fiction entirely (although both returned to it in the following decades).

Yet there’s a reason many commentators (this one included) proclaim the nineties a watershed decade for horror fiction. Some exhilarating novels of real innovation emerged, such as THE CIPHER by Kathe Koja, THE BRAVE by Gregory McDonald, VIRGINTOOTH by Mark Ivanhoe, X,Y by Michael Blumlein, CHANGELINGS by Tom Marshall and THE BLIND GOD IS WATCHING by Nancy Springer, in addition to noteworthy experimental horror-fests like THROAT SPROCKETS by Tim Lucas, MASTERY by Kelley Wilde and ESCARDY GAP by Peter Crowther and James Lovegrove. The latter harkens forward to HOUSE OF LEAVES in its overriding conceit: its narrative of an evil circus train wreaking havoc on a small American town is presented as a story being dreamed up by a frustrated novelist, which gets the authors off the hook for their stereotypical portrayal of small town Americana (i.e. the train arriving in the midst of a hamburger eating contest), much in the same way HOUSE OF LEAVES’S story is related by the fictional Zampano, who apparently takes the blame for the narrative inconsistencies that at times plague the text.

Re-reading the novel for the first time in twenty years, I found it didn’t go down as well as it did back in 2000—when I got through it in a marathon two day reading session. The perusal this time around was more laborious, with MZD’s many outré quirks (meaningless lists, multiple lines of blank text, crossed-out words, etc.) irritating me far more than they previously did. There’s also the fact that the once-hip wraparound, of Johnny and his quintessentially Gen X misadventures, now seems quite dated, functioning as more of a distraction from the Zampano drafted account of the morphing house rather than complimenting it, as appears to have been the intent (a close reading of the book indicates a number of subtle but distinct similarities between the two dueling narratives).

Another problem is that, simply, this once-unprecedented novel has been so widely imitated it no longer seems all that novel. Experimental horror novels may have proliferated in the nineties, but in the 00s they assumed an overtly HOUSE OF LEAVES-ish vibe. See DEMON THEORY by Stephen Graham Jones, THERE IS NO YEAR by Blake Butler, S. by J.J. Abrams and Doug Dorst, and BATS OF THE REPUBLIC by Zachary Thomas Dodson, all of which owe something to MZD’s classic.

One essential element all those novels have in common is a highly visually oriented aesthetic. That’s very much in keeping with HOUSE OF LEAVES, which is nothing if not design-conscious. One element that makes it unprecedented, even among its imitators, is the fact that the layout and design of its American trade paperback edition haven’t changed significantly during its twenty year lifespan, during which time the book has gone through multiple printings. The size, formatting and cover art of HOUSE OF LEAVES’ current edition all look exactly the same as they did back in 2000 (the only major changes I was able to detect were an opening page of enthusiastic blurbs that wasn’t present in the first edition, and the fact that certain illustrated portions of the text are now colored in, in place of the original black and white).

During those twenty years MZD kept himself busy. A second novel, ONLY REVOLUTIONS, appeared in 2006; some claim it’s a masterpiece while others (many others) find it incomprehensible. That was in addition to a couple short stories packaged as novels (THE FIFTY YEAR SWORD and THE LITTLE BLUE KITE), and THE WHALESTOE LETTERS, consisting of the letters that conclude HOUSE OF LEAVES together with some previously unpublished ones. For a time it seemed that MZD was on his way to becoming the Patrick Suskind of the 21st Century (i.e. an author who after publishing a successful debut novel grows progressively silent), at least until 2015, when volume one of THE FAMILIAR, a massive five volume epic for which MZD was paid a reported seven figure advance, appeared. THE FAMILIAR, which has been described as being about “a 12-year-old girl who finds a kitten and sets off a chain reaction with global consequences,” was certainly an ambitious undertaking, but it failed to recapture the spell cast by HOUSE OF LEAVES.

Thus it makes sense that in 2018 MZD decided to revisit his most iconic book in the form of a TV pilot adaptation. Initially posted on MZD’s Twitter feed (and since removed), his 62 page HOUSE OF LEAVES script is less an adaptation than a reimagining of the novel (which is as close to unfilmable as it’s possible to get), a gist that was furthered in scripts for two subsequent episodes for the prospective TV series that MZD has made available on etsy. How close these scripts have gotten to production, or if they’ve even started down that road, I don’t know.

The pilot script begins with MZD himself, in a Charlie Kaufman-esque touch, getting hounded by the media for perpetuating a hoax regarding HOUSE OF LEAVES; it seems he lied by claiming the book was fiction, when in fact it wasn’t. We also get snatches from a Donald Trump speech on a car radio, suggesting that MZD was also concerned with updating his two decades’ old tome to modern times.

Scrambling the book’s chronology quite dramatically, Zampano isn’t introduced until the final ten pages. Much of the preceding ones focus on Johnny, who in terms of attitude is mostly as he is in the text. Here, though, he discovers a box full of film canisters made by Zampano (rather than a book), with the business in the house confined to a few a short snippets that occur at roughly the midway point. There are also professors who periodically comment on the action, in place of the book’s analytic commentary (Stephen King and Hunter S. Thompson evidently weren’t available).

The HOUSE OF LEAVES pilot script is a reasonably compelling, clever piece of work that can’t hope to capture the overpowering strangeness and apprehension of its source text. But the fact that it manages to convey a fraction of such an individualistic book is, I guess, impressive enough.