In the lexicon of horror movie iconography, two titles stand far and above the rest as, arguably, the most famous in history. They are, as you’ve probably figured out already, DRACULA and FRANKENSTEIN.

In the lexicon of horror movie iconography, two titles stand far and above the rest as, arguably, the most famous in history. They are, as you’ve probably figured out already, DRACULA and FRANKENSTEIN.

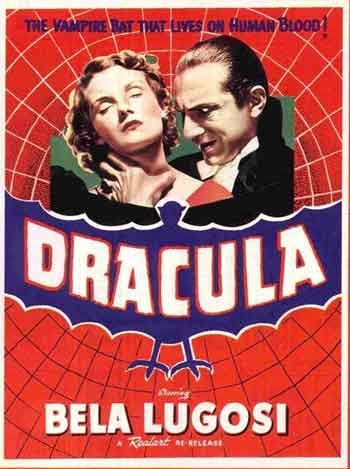

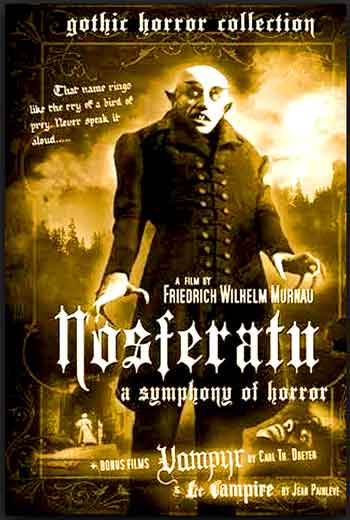

I’m referring, or course, to the “original” versions of these oft-filmed tales, both released in 1931 by Universal Studios (although, for the record, neither film is truly “original,” as DRACULA had already been filmed in 1922’s NOSFERATU and FRANKENSTEIN in a 1910 one-reeler). Countless sequels, remakes and parodies have followed in their wake, while memorabilia sales remain steady. So encompassing are these films that they’ve eclipsed pretty much everything else their respective stars Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff have done. Ditto the directors Todd Browning and James Wale.

Yet an inescapable fact remains, one few are willing to acknowledge: neither movie is very good.

It may seem rude or even, in light of the films’ overwhelming hold on popular culture, irrelevant to point out their respective faults, but in both cases some pretty extreme shortcomings exist. Take DRACULA. It wasn’t the first cinematic adaptation of Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel, and certainly not the last, but its impact remains monumental. It single handedly established countless horror movie clichés: the old cobwebby dark castles so integral to the genre owe their genesis to Browning’s film, as does the popular conception of the vampire as a smooth talking seducer (an image in direct contrast to the Dracula of Stoker’s novel, who had more in common with the hideous, rat-like bloodsucker of NOSFERATU, F.W. Murneau’s unauthorized adaptation).

It may seem rude or even, in light of the films’ overwhelming hold on popular culture, irrelevant to point out their respective faults, but in both cases some pretty extreme shortcomings exist. Take DRACULA. It wasn’t the first cinematic adaptation of Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel, and certainly not the last, but its impact remains monumental. It single handedly established countless horror movie clichés: the old cobwebby dark castles so integral to the genre owe their genesis to Browning’s film, as does the popular conception of the vampire as a smooth talking seducer (an image in direct contrast to the Dracula of Stoker’s novel, who had more in common with the hideous, rat-like bloodsucker of NOSFERATU, F.W. Murneau’s unauthorized adaptation).

To be sure, audiences of 1931 had never seen anything quite like DRACULA (a lawsuit brought by Stoker’s widow successfully kept NOSFERATU off the American market for many years). Its success was hardly surprising, but the film’s faults were undeniable, even back in 1931. Its makers’ biggest fumble, I believe, was in focusing more on a 1924 theatrical adaptation than the original text; it’s no surprise the resulting film is a stuffy talk fest with only intermittent flashes of creepiness.

And yet DRACULA has its share of supporters…although I doubt too many of these self-professed fans have actually bothered to sit through it. Those who have tend to grasp at straws in their defense of the film. The “stunning” mobile camerawork is most often singled out for praise, which makes sense, as cinematographer Karl Freund is generally acknowledged to be the film’s real maker, while Browning, the genius behind FREAKS and many other horror classics, essentially slept through the job on DRACULA. In any event, both men deserve blame for the frequently terrible framing and numerous technical gaffes (such as a plainly visible sheet of paper placed under a lamp to diffuse the light). David J. Skal, in his DVD audio commentary, mentions at one point that “one gets the feeling no-one is in the director’s chair, or behind the viewfinder.”

yet DRACULA has its share of supporters…although I doubt too many of these self-professed fans have actually bothered to sit through it. Those who have tend to grasp at straws in their defense of the film. The “stunning” mobile camerawork is most often singled out for praise, which makes sense, as cinematographer Karl Freund is generally acknowledged to be the film’s real maker, while Browning, the genius behind FREAKS and many other horror classics, essentially slept through the job on DRACULA. In any event, both men deserve blame for the frequently terrible framing and numerous technical gaffes (such as a plainly visible sheet of paper placed under a lamp to diffuse the light). David J. Skal, in his DVD audio commentary, mentions at one point that “one gets the feeling no-one is in the director’s chair, or behind the viewfinder.”

Of course, the one quality I can’t argue with is the lead performance of Bela Lugosi, still the most suave and seductive vampire in movie history. Lugosi’s appearance, mannerisms and accent in DRACULA are justifiably iconic, and literally impossible to forget once experienced. It’s just a shame he wasn’t given more to do by the filmmakers.

DRACULA is, in the end, a completely under whelming experience, undeserving of all the attention it’s received. I feel the same way about most of the sequels and remakes that have followed in the years since (yes, this does include John Badham’s lame 1979 version and Francis Ford Coppola’s overdone 1992 attempt). The finest incarnation of DRACULA remains Bram Stoker’s novel, which, over a hundred years after its original publication, remains a singularly creepy and perverse achievement…NOT like the movies adapted from it.

DRACULA is, in the end, a completely under whelming experience, undeserving of all the attention it’s received. I feel the same way about most of the sequels and remakes that have followed in the years since (yes, this does include John Badham’s lame 1979 version and Francis Ford Coppola’s overdone 1992 attempt). The finest incarnation of DRACULA remains Bram Stoker’s novel, which, over a hundred years after its original publication, remains a singularly creepy and perverse achievement…NOT like the movies adapted from it.

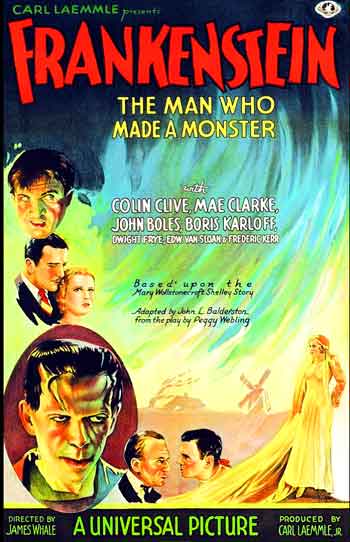

I would say the same for Mary Shelley’s FRANKENSTEIN, OR THE MODERN PROMETHEUS (1818), but I find it pretty musty overall. To me, the circumstances of the novel’s gestation—a drug-filled gathering Shelley attended on June 16, 1816, which also inspired John Polidori’s classic THE VAMPYRE—are far more interesting than the story itself. The book does contain isolated passages of brilliance, though, which places it several leagues ahead of the 1931 movie adaptation.

Actually, the FRANKESTEIN we all know and (supposedly) love is a bastardization of Shelley’s text. Like DRACULA, the film was patterned more closely after a stage piece which had very little to do with the book (it omits the immortal line “Grant me my wedding night or I’ll be with you on yours!”). In place of Shelley’s epic narrative, we’re left with—again—a stodgy, creaky filmed play. That impression is underlined by the patently obvious stage-bound sets, whose artificiality is made clear by the echoing voices and, in the opening scene, an actor’s coat hitting a painted backdrop with an audible thunk! Indeed, FRANKENSTEIN is an excellent film to show film students, as, in its clumsiness, it highlights the importance of sound, and music in particular (which, in an unfortunate early thirties movie convention, is completely absent but for the opening and closing sequences).

Actually, the FRANKESTEIN we all know and (supposedly) love is a bastardization of Shelley’s text. Like DRACULA, the film was patterned more closely after a stage piece which had very little to do with the book (it omits the immortal line “Grant me my wedding night or I’ll be with you on yours!”). In place of Shelley’s epic narrative, we’re left with—again—a stodgy, creaky filmed play. That impression is underlined by the patently obvious stage-bound sets, whose artificiality is made clear by the echoing voices and, in the opening scene, an actor’s coat hitting a painted backdrop with an audible thunk! Indeed, FRANKENSTEIN is an excellent film to show film students, as, in its clumsiness, it highlights the importance of sound, and music in particular (which, in an unfortunate early thirties movie convention, is completely absent but for the opening and closing sequences).

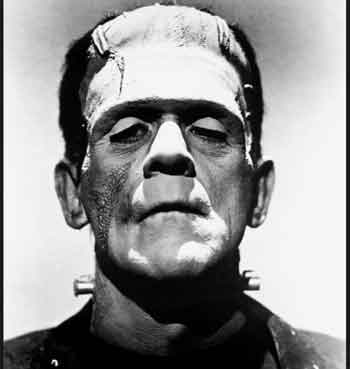

Again, however, FRANKENSTEIN was a monster hit upon its original release and, like DRACULA, established many horror movie conventions. It’s greatest innovation was in presenting its monster as both horrifying and curiously sympathetic. Nowadays, though, the horrific aspects have completely worn off; the creature, after all, is presented as a victim from its inception (Dr. Frankenstein’s dweeb assistant drops the “Normal” brain on the ground and so grabs the “Abnormal” one) to eventual murder for the crime of throwing a young girl into a lake, where she drowns about a foot from the shore (I think the girl’s parents should shoulder at least part of the blame, as they live by a lake yet didn’t bother teaching their child to swim!). Boris Karloff’s touching performance, easily the movie’s highlight, only enhances the terminally unscary vibe (a ludicrous bit where Karloff menaces a woman is plain gratuitous).

As with DRACULA, a flood of sequels and remakes followed in FRANKENSTEIN’S wake, including James Whale’s 1935 BRIDE OF FRANKENSTEIN, which was superior to the original in every respect (not so, however, for the likes of FRANKENSTEIN: THE (un)TRUE STORY, BLACKENSTEIN, MARY SHELLEY’S FRANKENSTEIN, etc.), yet it’s still taken a back seat to it in popularity. Ditto FLESH FOR FRANKENSTEIN (1974) and THE LAST FRANKENSTEIN (1992), both of which presented perverse, thought-provoking variants on Mary Shelley’s conception, and both far more interesting, in my view, than the story’s most famous screen incarnation.

And yet people continue to espouse the 1931 film’s greatness (although recent attention has focused more on director James Whale, successfully profiled in 1998’s GODS AND MONSTERS, than the film itself). The contributions made to the genre by FRANKENSTEIN and its predecessor cannot be overestimated…but I’d strongly suggest actually viewing both films before proclaiming them great!